Psychology

Understanding Games of Baiting and Daring

Social games described in literature reveal a psychology of strategy.

Posted May 13, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Teasing is a risky social game.

- Dostoevsky describes such games in “The Gambler.”

- Awareness of one’s own preferences and strategies can protect a person from exploitation.

She too could not live without me. – Alexei pining for Polina

Alexei Ivanovich, Dostoevsky’s fictional alter ego in his short story, The Gambler, gambles and wins—at least for a spell. In his social games, he is less successful. His love for the heiress Polina Alexandrovna is unrequited, or so it appears till the very end. Polina plays games with Alexei, two of which we shall consider here, using game-theoretic tools introduced in other essays (see Krueger, 2022a, for a recent discussion of a game of guilt and power).

Teasing and baiting

In the first game, Polina shows her mastery of the tease. Knowing that Alexei desires her, she refuses to reveal her intentions. Instead, she stokes his hopes with requests for help (e.g., to gamble on her behalf with her money), veiled allusions, and things she could say but does not. Alexei confides that “She loved suddenly to torture me with some fresh outburst of contempt and aloofness! Yet she must have known that I could not live without her.” He goes on to conclude that “She too could not live without me, for had she not said that she had need of me? Or had that too been spoken in jest?”

Poor Alexei tries everything to win her favor; he even makes her rich after a lucky run at the casino, but we find out Polina controls the game. Or does she? A closer look at this Game of Bait is instructive. We begin by making reasonable assumptions about the preference rankings of the teaser and the teasee.

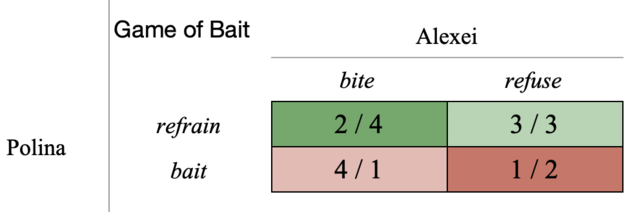

Matrix 1 shows that both have a choice between two strategies. Polina can refrain from baiting Alexei (i.e., cooperate) or tease him (defect). Alexei can bite (cooperate) or refuse (defect). Higher numbers refer to better value for the player. Within each of the four cells of the matrix, the number to the left indicates Polina's preference and the number to the right refers to Alexei's preference.

Polina would surely most enjoy having Alexei swallow the bait [4]; it would affirm her power. Her second preferred outcome is to not bait a recalcitrant Alexei in the first place [3], followed by having Alexei—pointlessly—submit to her without her asking [2]. Polina’s least preferred outcome is to see her bait refused, as this would humiliate her [1]. We suspect that Alexei would most prefer not to be teased and yet approach Polina successfully [4] followed by staying away from an aloof Polina [3]. His third preference is to resist the bait [2], while his worst outcome is to be baited into a humiliating approach [1].

With these conflicting sets of preferences, the battle lines are drawn. The critical feature of this bait game is that it has no equilibrium state. For any of the four outcomes, there is one player who can do better by switching strategies. When Polina baits Alexei she should expect him to stay aloof. Her baiting him reveals her need for power and her myopic neglect of the rational countermove. Alternatively, she recognizes Alexei’s masochistic streak and the satisfaction he takes in being humiliated. In short, the preferences held by reasonable people, which are shown in the matrix, may not be the preferences Dostoevsky attributes to 19th-century Russian aristocrats and social opportunists.

Daring the chicken

In the second game, which precedes the first in the story, Alexei appears to be in the driver’s seat. Having ascended the “Schlangenberg” [Snake Mountain, presumably the Neroberg north of the Wiesbaden Casino], Alexei offers to “leap into the abyss.”

“Just but the word’” he dares Polina, “Had you said it, I should have leapt. Do you not believe me?’

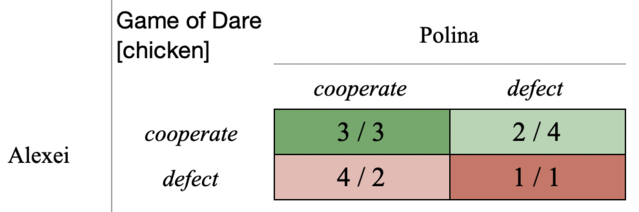

Matrix 2 shows Alexei as the row player. He has a choice between being a gentleman (cooperation) and a daring provocation (defection). Polina, the column player, chooses between cooperative accommodation (“Don’t jump!”) and calling the bluff (defection)—if it is a bluff. Note that a reasonable preference ranking is symmetrical, revealing a game of chicken (Krueger, 2022b). Both players prefer most to have their defection stand, followed by mutual cooperation, and lastly, by the catastrophe of finding that the dare was no bluff.

As Alexei moves first, he has the power to force Polina to accommodate him. Had she pleaded with him not to jump, perhaps even desist for her sake, Alexei might have received the signal of love he so craved. Alas, Polina is the more cunning strategist. She knows how to win a game by stepping out of it.

“What stupid rubbish!” she cries, deflating Alexei.

Dénouement

There are many ways to read literature, and Dostoevsky offers plentiful possibilities for fresh interpretation. Freud (1928) credited his literary genius with anticipating elements of what became depth psychology. I wrote this essay to dare you to see that some psychological insights lie in plain sight. A semi-fictional character like Alexei Ivanovich is embroiled in many social games that are all too familiar. A little analysis can go a long way to clarify our own preferences and guide us toward a better outcome next time when a cunning player teases or dares us.

How did it end for Alexei and Polina? Dostoevsky hands Polina a final victory when he allows her to humiliate Alexei one last time. The pasty Englishman Mr. Astley reports to Alexei, “Yes, poor unfortunate. She did love you: and I may tell you this now for the reason that now you are utterly lost.” It is too late for Alexei to see this love become reality, which Polina appears to know. Her missive is a cruel joke, a spiteful strategic move in a meta-game, the psychological comprehension of which might require some depth psychology beyond game theory.

References

Dostoevsky, F. (2003). The gambler. Modern Classics. First published in Russian, 1869.

Freud, S. (1928). Dostojewski und die Vatertötung [Dostoevsky and parricide]. In R. Fülöp-Miller & F. Eckstein (Eds.), Die Urgestalt der Brüder Karamasoff (pp. xi-xxxvi). Eckstein

Krueger, J. I., (2022a). Guilt and power. Psychology Today Online. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/one-among-many/202205/guilt-and…

Krueger, J. I. (2022b). Cooperation and defection in two social games. Psychology Today Online. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/one-among-many/202205/cooperati…