Happiness

Pleasure and Pain

The distribution matters.

Posted February 6, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

¡Gracias a la vida, que me ha dado tanto! — Violeta Parra

Odysseus, "man of many devices" (polytropos), had most of his epic adventures behind him three years after leaving Troy. Then, with all his ships having sunk and all his friends dead, he finds himself on the island of Ogygia, alone with the goddess Calypso, "she who conceals."

For seven years, he longs for his home, Ithaca, and he cries out to the gods for help. Zeus sends Hermes to instruct Calypso to let Odysseus go. She doesn’t take it well, at first, for she loves Odysseus and she had promised him eternal life (and love) in her alluring company. Odysseus, being insistent and with the backing of the top Olympic brass, prevails. Calypso makes a raiment for him and allows him to build a raft, though not without warning him that if he only knew the troubles and griefs fate held in store for him, he might think better of his plan.

There is a lot of psychology here, with the core question being why Odysseus chooses the way he does. It is easy to moralize the story and conclude that missing one’s family and feeling the responsibility of rejoining them are virtuous instincts, so noble, in fact, that everlasting bliss in the Bronze Age version of Club Med cannot blunt them. Morality 1: Hedonism 0.

Being critical of received Western narratives, Horkheimer & Adorno (2002/1944) viewed the Odyssey as an ethnographic tale of the rise of the patriarchy, where the institution of bourgeois marriage comes to anchor society. They assert that “woman remains powerless in that her power is mediated to her only through her husband. Something of this is reflected in the defeat of the courtesan-goddess of the Odyssey [Calypso], while the fully evolved marriage with Penelope ... represents a later stage in the objective structure of patriarchal arrangements” (p. 56). Penelope, the dutiful housewife, prevails over the courtesan-goddess, but her victory is hollow. It requires submission to her reinstated husband.

Perhaps Odysseus chooses to leave the island of Ogygia for reasons of true yearning and uxorious love. Then again, he spent 10 years at the gates of Troy, scheming and battling to sack the city without relenting for the sake of an early return to Ithaca. Perhaps then his true reason for his homecoming is a desire to reassert his power as king and paterfamilias. There is nothing in the Odyssey to directly refute this idea. There is, however, an alternative explanation: Odysseus is bored! Every day with gorgeous Calypso is, after all, pretty much the same: sensual delights in the morning, fresh seafood, followed by more sensual delights in the afternoon, ad infinitum and ad nauseam.

Decades of research have shown that humans and other organisms (even neuron-free slime molds; Boisseau et al. 2016) habituate to constant stimulation and adapt to their circumstances. Adaptation Level Theory (ALT, Helson, 1947) gives mathematical expression to the relativity of subjective experience. Organisms mainly respond to changes in stimulation. Unchanging stimulation quickly becomes uninformative. We cease to get a rise out of it. Although Odysseus knows that the pleasures of today will renew themselves tomorrow, what is the point? Ultimately, he may come to see value even in hardship and suffering, for it tells him that he is alive and evolving, and, with pains overcome, he (and then Homer) will have a good story to tell (do they ever!).

Most of us do not get to make choices where one option includes immortality and everlasting bliss. We live in a finite world. The basic tenet of hedonism is that we seek happiness by maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. By and large, most of us live by this iron rule; it helps us learn, survive, and leave descendants behind to do it all over again. We have, however, additional sensitivities and sensibilities that go beyond the mere summation of all pleasures (+) and pains (-). One additional property of experience is that hedonic events can differ in their intensity and frequency. There can be one superb moment of bliss or several smaller pleasures adding up to the same total hedonic scale value, and likewise for pains. Another property is the sequence of experiences. Does pleasure precede pain or vice versa?

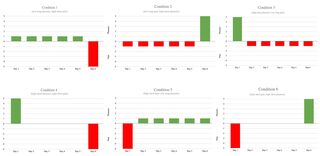

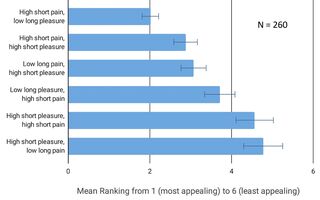

My student collaborators Anna Cohenuram, Erin Gresalfi, Zachary Mulligan, and Tanushri Sundar, and I created six simple scenarios, each showing a different week-long course of pleasure/pain a person might experience. The schematic on the left shows the scenarios. Pleasure is indicated by green columns and pain is indicated by red columns. A column is either 1 or 5 points in height or depth. The sum total over the 6 days is 0 in each scenario. We asked 260 students in a course on happiness to rank the scenarios according to their desirability or attractiveness, with 1 being the best and 6 the worst. Simple hedonism provides the null hypothesis. If only the sum total mattered, the average ranks would be statistically the same, hovering around 3.5.

This null hypothesis did not do well. As shown in the graph on the left shows, mean ranks varied by over 2.5 points from the lowest (best) to the highest (worst). A closer look at the ordering reveals interesting patterns. The first principle of differentiation is order. The top 3 scenarios have one thing in common. Pleasure follows pain. Their mean rank is 2.66, which is statistically lower (better) than the expected (null hypothesis) mean rank of 3.5, t(779) = 15.85, d [the standardized effect size] = .57. This finding replicates a well-known phenomenon according to which people remember episodes by how they end (Redelmeier & Kahneman, 1996). Our respondents preferred hedonic sequences that end with pleasure. The most popular sequence is also consistent with the predictions of ALT. Once the intense but brief pain is gone, each day brings a little pleasure. Adaptation generates a running average, but this average is updated every day. Although this is a hedonic treadmill (Brickman & Campbell, 1971), it might be preferable to a mere "treadmill." Indeed, Brickman & Campbell mused whether “the happiest adult is one who had a moderately unhappy childhood.” However, contrary to their assertion that subjective pleasure is an illusion because it is transient, it is only lasting — or chronic — pleasure that is illusory.

The second principle is a preference for distributed (as opposed to short and intense) pleasure (scenarios 1 and 4 vs. 2, 3, 5, 6), M = 2.87, t(519) = 8.34, d = .37. This finding supports the Range-Frequency Theory (RFT) of judgment, according to which ‘renewable’ pleasures trump intense but fleeting ones (Parducci, 1965). The final principle is a preference for short, intense pains over frequent, though milder ones (1, 2, 4, 5 vs 3 and 6), M = 3.29, t(1039) = 4.03, d = .12. The third principle is the flipside of the second, again supporting RFT.

These findings turned out as they should because theories of psychophysical judgment are quantitative models describing observed data patterns. There are circumstances where these theories make competing predictions, but the goal of this exercise was not to do a crucial experiment. We can say, however, that the scenarios ending on a note of great pleasure did not take first place, as a strict interpretation of Kahneman’s peak-end rule might have predicted. Nor is it the case that only the sum total of happiness matters, as early theories have hedonism would have it. Finally, our respondents roundly refused to walk the path of impatient hedonism; they rejected both scenarios beginning with intense pleasure.

Odysseus rejected unbounded hedonism for a finite life, which included suffering as well as joy. Some say that the joys of life are sweet because they must be conquered (Russell, 1930) and because they cannot be repeated at will. Perhaps Odysseus, a man of myth, foresaw that everlasting bliss is the true dreadmill and that eternal life cannot end on a high note.

References

Boisseau, R. P., Vogel, D., & Dussutour A. (2016). Habituation in non-neural organisms: evidence from slime moulds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 20160446.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. 1971 (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Apley (ed.), Adaptation level theory: A symposium (pp. 287–302). Academic Press.

Helson, H. (1947). Adaptation-level as frame of reference for prediction of psychophysical data. American Journal of Psychology, 60, 1–29.

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, Th. W. (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment. Edited by G. S. Noerr, translated by E. Jephcott. Stanford University Press. Originally published in German as Dialektik der Aufklärung, 1944.

Parducci, A. (1965). Category judgment: A range-frequency model. Psychological Review, 72, 407–418.

Redelmeier, D. A., & Kahneman, D. (1996). Patients' memories of painful medical treatments: Real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain, 66, 3–8.

Russell, B. (1930). The conquest of happiness. Allen and Unwin.