"The happiness of a given life is not to be measured according to the joys and pleasures it contains but according to the absence of the positive element, the absence of suffering." — Schopi

In a previous foray into the land of pleasure and pain, we learned that respondents in an informal survey favored a scenario in which sharp but brief pain was followed by small but repeated pleasures over a variety of alternative scenarios with the same overall average value (Krueger, 2021). This result satisfies theories of psychophysical judgment (see Luhmann & Intellisano, 2018, for an overview), and J. S. Mill who favored “an existence made up of few and transitory pains, [and] many and various pleasures” (as cited in Haybron, 2008, p. 145).

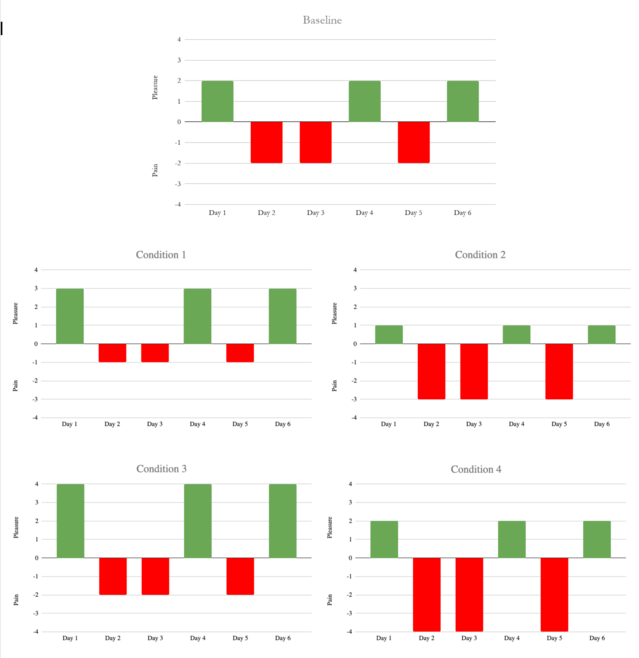

We pressed on by asking the following question: How do people respond to an increase in both pleasure and pain, and does it matter if the average over the pleasures and pains rises or falls? Consider the top panel of the figure above. Over 6 days, the hedonic state is either +2 on a good day or -2 on a bad day. The average is 0. In the two panels below this baseline scenario, 1 pleasure point is added (condition 1 on the left) or subtracted (condition 2 on the right) to each day, so that the average is respectively +1 or -1. In the two bottom panels, 2 pleasure points are added to each pleasant day (condition 3 on the left) or 2 points are subtracted from the below-0 days (condition 4 on the right) compared with baseline. In other words, conditions 1 and 3 are both pleasant on average (M = +1), but the range of experience is greater in condition 3 (range = 6) than in condition 1 (range = 4); conditions 2 and 4 are both unpleasant (M = -1) with a greater range in condition 4 (6) than in condition 2 (4).

Surely, we prefer a favorable pleasure-pain balance (conditions 1 and 3) over an unfavorable one (conditions 2 and 4). The question is, are we sensitive to differences in day-to-day variation? Do we prefer the relative serenity of condition 1 over the wild ride in condition 3? And if we have a preference for a low or a high amplitude of hedonic experience, is it the same irrespective of the overall average?

Students in a lecture course (N = 233) ranked the 4 critical scenarios (not the baseline) in terms of how appealing they found them. The figure above shows the average ranks. Lower numbers represent greater appeal. Not surprisingly, the students preferred a positive pleasure-pain ratio. Let’s consider this a successful attention check. Of interest is the difference between scenarios 1 (serenity, bright red) and 3 (wild fun with some pain, saturated red). Serenity wins, t(232) = 4.26, p = 2.94E-05. Again, psychophysics can help explain why. Pains are more intense than pleasures of the same nominal value; hence a symmetrical increase in variation tilts the overall experience to the negative. For a peak experience to be attractive, it needs to be far better than the pain that must be endured to achieve it.

This logic, if it were flawless, should have given us a significant preference of low-amplitude misery (condition 2, bright blue) over the wilder oscillations of condition 4 (sad blue). But this difference, though seen by the naked eye, was not statistically significant, t(232) = 1.81, p = .07, two-tailed, though it would be significant if we cleverly declared that a one-tailed test would do — because we saw it all coming.

This leaves us with a yin and yang of interpretation. Here is the yin: Perhaps when it comes to pain, people ignore its intensity. They think categorically. Pain is pain. This speculation runs up against the psychophysics of loss, though, which is that people discriminate more among losses than among pleasures of the same nominal value (Tversky & Kahneman, 1979). That leaves the yang of the ordering of the 4 conditions as we see it. Averages aside, we prefer less variation to more. Variation, though exciting and titillating in its own right (“I have never felt so alive!”) also brings the burden of uncertainty and the effort of adjusting to sudden changes. Serenity has the meta-appeal of protection from "perturbations of the soul" — as does a chronic, if unpleasant, state of mild unhappiness.

If Schopenhauer knew of the dominance of pain (see epigraph), he obliquely hinted at the comparative serenity of nothingness. Wrote he: You can also look upon our life as an episode unprofitably disturbing the blessed calm of nothingness.

I thank Erin Gresalfi, Zach Mulligan, and Tanushri Sundar for their help with this project.

References

Haybron, D. M. (2008). The pursuit of unhappiness. Oxford University Press.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-291.

Krueger, J. I. (2021). Pleasure and pain. Psychology Today Online. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/one-among-many/202102/pleasure-…

Luhmann, M., & Intellisano, S. (2018). Hedonic adaptation and the set point for subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers.