Persuasion

Collaborative Attitude Change

What would it take to change your mind?

Posted February 17, 2020 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

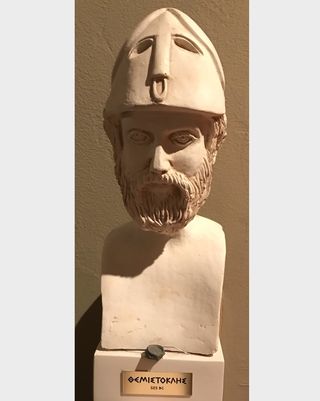

I have with me two gods, Persuasion and Compulsion. – Themistocles of Athens

The social psychology of persuasion and attitude change tells two different stories. One story is that persuasion is easy. The other story is that it is hard.

The easy story is well told by Robert Cialdini (1984) and all the nudgers (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008) who succeeded him. The hard story has fewer champions in the field (see Abelson & Prentice, 1989) but it has greater power to frustrate us at home and at the office. The easy story rings true when the targets of influence (persuasion or calls for compliant behavior) are not paying attention, or if their attitudes are weak, ill-formed, or non-existent. The hard story wins when attitudes are ego-involving, broad, extreme, or anchored in cultural certitudes, taboos, or verities (Tetlock, 2003).

We all know the frustrations that come with futile persuasion attempts. The defeat repercusses. We feel regret at the time wasted, shame at our failure to do better, and most likely anger at the target’s "unreasonable" stubbornness. How may we diminish these frustrations, and how might we even prevail over our targets a bit more often than we usually do?

The first option is to stand back and refrain from any persuasion attempt. This may sound strange, but it is not crazy. Perhaps we can be content with learning what other people think, how they feel, and what they value without seeking to change them. It might almost seem too saintly, and exceptions readily present themselves. We go into persuasion mode when it is in our vital interest to get a mugger not to mug, or if it is in the vital interest of a dependent to do something they do not wish to do, such as eating their breakfast and going to school. These exceptions stand, but we may wonder how often we try hard to change someone’s mind when there is no instrumental advantage to be had other than the vain wish to get them to agree with us.

The second option is to hazard a forecast as to how likely it is that the target’s mind is open to evidence and argument, and how likely it is that the person will be persuaded. It is surely hard to make a good forecast, but my impression is that we usually do not even try. We jump to the desire to persuade without reflecting first on the odds of success. To make a forecast, we can ask where the attitude at stake falls in the space of the criteria listed above. Are we in Cialdini’s world or in Tetlock’s territory? If the latter, it’s best to walk away or change the topic. If the former, we still need to decide whether we wish to be clever and appeal to intuition or affect, or if we want to be earnest and appeal to reason.

The third option – and this is the point of this essay – is to clear the ground first by asking the question of what it would take, from the target’s own point of view, to have his or her mind changed. This only seems to be an odd question because it is so rarely asked, and those who do ask it (“What will it take to put you into this lovely little convertible?”) do not enjoy the finest reputation of trustworthiness. But think about it. To engage in a persuasive attempt is to commit to significant effort. Would we not want to know how much effort is required and what the odds of success are if we put our best effort forward?

Many of the contemporary debates, particularly in the political arena, are rather like sermons delivered to the faithful. At best, they are calls to action directed at those who already agree with the sentiments presented but who need a little energy to go and act. Minds are not being changed here. By way of self-experimentation, ask yourself what it would take to switch your political or religious allegiance. You may find that it can’t be done, and this tells you that it will be no different for most other people. There is more room for movement on specific issues because specific issues do not threaten an entire worldview (unless the target thinks through all the implications of local belief change, and they usually don’t). So start there.

When you ask someone "What kind of evidence (or argument) would change your mind on X?", you might be seen as aggressive and be dismissed because of that. So ask gently but stick to the question. It gives you a strategic advantage. The first possibility is that the target declares that there is no conceivable evidence to change her (or his) mind. If so, you can agree that this particular attitude is of the sacred kind. This itself might be a new insight for the target, and her reaction – proud or sheepish – tells you a bit more about her. The persuasion attempt will be over, though. You might wish to press on and ask why this particular attitude should be impenetrable, but the conversation will likely not be a pleasant one.

The second possibility is that the target declares that she is open to evidence but then sets the bar impossibly high. This is a smart move. You might respond that the target is effectively saying that nothing will change her mind, and you are back to the first scenario. Politeness dictates, however, not to argue with the target’s response to your "What would" question. Let her draw her own conclusions about herself.

The third possibility is that the target provides a standard that can actually be met, in which case you both have something to work with, and the work of persuasion might turn from an adversarial exercise into a collaborative one.

My point is that the failure to ask and to answer the "What would it take" question is nearly ubiquitous and one of the sources of interpersonal friction and intergroup strife. All too often, people reflexively and affectively react with disbelief and anger to the beliefs of others; they jump to aggressive attempts to change their minds, fail, and get angrier still. Clearing the air upfront can avert much psychological harm.

In my years as a blogger, some beliefs have crystallized for me that are now harder to change than they were then. Many of these beliefs are negative in the sense that I do not believe in things many other people do believe in. For example: God, free will, telepathy (I do believe in engipathy), Plato’s theory of forms, the value of regret or retribution, the Sasquatch. If you ask me what it would take to change my mind, I would say there is little that could. But these beliefs are not of the sacred kind. I hold them either because there is no evidence (God, the Sasquatch), because the evidence is terribly weak (retribution), or because too much else in my worldview would have to change if I changed this belief (e.g., if I accepted the possibility of backward causation).

The failure to ask the "What would it take question" is, in my opinion, particularly distressing in the political conversation, or what is left of it. Two examples (among others) come to mind. No one, as far as I can tell, asked those elected officials who opposed the impeachment of the president what their threshold of an impeachable offense might be. Of course, for some of them, we know because they felt 20 years ago that one lie under oath is enough. If so, should not an accused president testify under oath?

Another example is gun control. If one side argues that the current level and kind of gun violence is insufficient for the taking of action, might it not make sense to ask for an explicit threshold? Instead, their opponents insist that the threshold has long been surpassed, but this will do nothing in the game of persuasion. They are tautologically referring to their own threshold when they should be concerned with the threshold set by the targets. Ask the target what they think will change their minds, and hold them to it.

Now, these are two examples that came to my liberal mind. My point, though – I insist – is a general one. I invite conservative readers to provide examples to challenge the liberal mind. We can all learn from this exercise.

References

Abelson, R. P. (1995). Attitude extremity. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 25–41). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Abelson, R. P., & Prentice, D. A. (1989). Beliefs as possessions: A functional perspective. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 361–381). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cialdini, R. B. (1984). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Quill.

Tetlock, P. E. (2003). Thinking the unthinkable: Sacred values and taboo cognitions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 320–324.

Thaler, R. & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.