You think you’re better than me, huh? ~ Izzy Mandelbaum, played by Lloyd Bridges, on Seinfeld

Seinfeld once satirized self-enhancement. Izzy Mandelbaum, an elder gentleman played by Lloyd Bridges, keeps challenging Seinfeld with the question “You think you’re better than me?” Each time Izzy proceeds—over Jerry’s protestations—to attempt to lift a heavy object, each time with the result of a loud crunching sound emanating from his back and attendant paralysis.

Who’s self-enhancing here and how is self-enhancement perceived? Whether Seinfeld self-enhances (he denies it) I don’t recall, but Izzy thinks he does, and he (Izzy) doesn’t like it. In turn, Izzy quite obviously tries to demonstrate that he is better than Seinfeld. It does not go well, as proven by the crunch and paralysis, which reveals Izzy as a false self-enhancer, as someone who commits an error of self-enhancement.

In social psychology, the basic self-enhancement effect is well established—with some equally well-understood exceptions. For most people and most contexts, self-perceptions are more favorable than perceptions of the average person. Most people think they are better-than-average drivers, happier and less selfish than average, and that they have higher self-esteem than the average person.

To be more inclined to say that you are better than average than to say you are worse is a bias. A bias is a response tendency. It is not the same as inaccuracy. Someone who claims to be better than average may indeed be better than average. In social psychology, there are two views of the functionality of self-enhancement. According to one view, self-enhancement is a useful bias. It allows the perceiver to feel good and it motivates optimism and engagement with the world, much like a confidence bias would (Taylor & Brown, 1988). According to an alternative view, self-enhancement is dysfunctional; it comes back to bite you. One eventually learns that others do not like self-enhancers. Self-enhancement thus threatens social connectedness (Kwan, John, Kenny, Bond, & Robins, 2004).

Neither view makes a clear distinction between the bias of self-enhancement, that is, the mere fact of making a claim of being better than average, and a self-enhancement error, that is, a claim of superiority that turns out to be false. Yet, both views consider self-enhancement bias a cognitive illusion, on a par with visual illusions: irrational, inaccurate, and impenetrable.

But is this the best way to think about self-enhancement? Is it not possible to consider self-enhancement, the claim to be better than average, a decision a person has to make after giving it some thought? The person might wonder ‘I can’t be sure that I am better than average. If I claim to be better, the facts may fall in my favor, and my claim is justified. However, it is also possible that I turn out to be wrong, which would leave me disappointed. Conversely, I might declare to be worse than average. If this turns out to be correct, then at least I made the right decision. Or it turns out that I am actually better than average, in which case I’d regret not having been more assertive in my prediction.

In short, when matched against reality, a claim to be better (or worse) than average can lead to four distinctive outcomes: a Hit (H), which is a correct claim of superiority; a False Alarm (FA) or self-enhancement error; a Correct Rejection (CR) or correct claim of inferiority; or a Miss (M) or a missed opportunity to declare superiority (Heck & Krueger, in press). Each of these outcomes has its own emotional consequences. H may produce pride, FA may produce shame, CR may produce righteous humility, and M may produce a blushing sense of sheepishness.

If we consider the decision of claiming to be better or worse than average a choice made under uncertainty, and if we assume that the decision-maker is not irrational, we must assume that the decision-maker weighs the in-store emotional consequences and their respective probabilities.

As for the valuation of the outcomes, we may assume that H has a high value, let’s say 10. A CR is ambiguous because it confirms inferiority while giving some gratification for being correct. Let’s give it the value of 5. A FA has a low value, with the possibility of providing a fleeting glow of positivity until the truth is revealed. Let’s assign it a 2. A Miss is also ambiguous; it extracts a penalty for having made a bad judgment, but also reassures the person of good standing. Let’s assign it a 6.

Clearly, the greatest gratification comes from a Hit, from claiming to be better than average and being proven right. The only way a person can even have a chance of experiencing this gratification is to claim to be better than average. If a person has no idea which side of the average she is on, she ought to assume she is better than average as long as the difference between the good feeling coming from H and the average feelings coming from CR and M is greater than the difference between the bad feelings coming from an FA and the average feelings coming from CR and M. This condition is met in our numerical example. If the value of H were 9 instead of 10, the person would be indifferent.

The above example assumes that whatever the person decides to predict – being better or worse than average – the decision is equally likely to be correct or incorrect. This assumption is too restrictive. Typically, there is a moderate positive correlation between self-perception and reality. A person who expects to be better than average is more likely a H than a FA, and a person who expects to be worse than average is more likely a CR than a M.

This accuracy correlation has tricky implications. Suppose a person knows of this correlation. While still being uncertain about being better or worse than average, it is now tempting to declare being better, knowing that statistically a positive self-perception implies a positive true state. But would this not be an instance of magical thinking? The simple act of declaring superiority cannot make it so. Self-perception has no causal power over reality. An accuracy correlation can only be credible if the perceivers assess themselves while not thinking about this correlation. Indeed, if most perceivers fell into magical thinking and declared being better than average, the accuracy correlation, which gave rise to their magical thinking, would shrivel and disappear, thereby negating its own effects.

Let us then assume a credible uncontaminated accuracy correlation is at hand. Let us assume this a correlation was obtained in one sample of naïve perceivers of good-will who had taken antibiotics to kill the magical-thinking bacteria. Now a new sample of perceivers comes along and they know that whichever decision they make, the probability of being correct is .6. Now the expected value of self-enhancement is pH + (1-p)FA and the expected value of self-effacement is p(CR) + (1-p)M, where p = .6. The result is 6.8 for self-enhancement and 5.4 for self-effacement. Given these values and probabilities, a rational perceiver self-enhances. Indeed, a rational perceiver would self-enhance as long as the probability of making a correct decision is greater than .44 ((M-FA)/(H-FA-CR+M)); that is, even if the correlation between perception and reality is slightly negative.

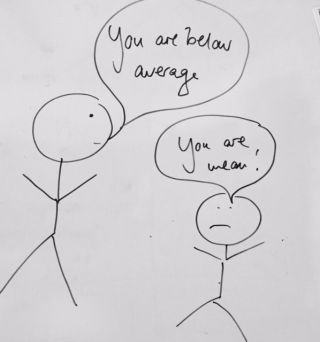

Would we, however, want to live in a world where everyone self-enhances? Probably not. Indeed, our own self-enhancement would ring hollow if everyone self-enhanced as well. Individual rationality runs afoul of collective rationality. Ideally, we’d like to be a Hit, and one of the few to boot. In a world where claims of superiority are made frequently and assertively, they easily take on an aggressive feel (as satirized by Seinfeld).

The race toward comparatively superior self-enhancement creates a prisoner’s dilemma. Often, self-enhancing claims are veiled by the lack of explicit comparisons. The claimant merely points to some achievement or extraordinary piece of consumption, assuming that the listener gets the implied I-am-better-than-you message. I have observed some cultural differences and themes. Germans love to mention their travels to exotic locations. Few are still impressed by tales of Machu Picchu, but a report from Tierra del Fuego or Macho Grande can still carry the day. In contrast, many Americans, for unfathomable reasons, still seek to impress others by claiming to work longer hours and take fewer vacations. Soon some might start to brag about being underpaid. The construction of a claim as self-enhancing is, for better or for worse, rather flexible.

Perhaps the wise course of action is to desist from making the decision to self-enhance at all, except when social psychologists ask us to. As the late psychologist and social dilemmatist Robyn Dawes noted, we can opt not to play. Or as Seinfeld put it (I paraphrase): “I can lift the weight; I choose not to.”

Heck, P. R., & Krueger, J. I. (in press). Self-enhancement diminished. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Kwan, V. S. Y., John, O. P., Kenny, D. A., Bond, M. H., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Reconceptualizing individual differences in self-enhancement bias: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Review, 111, 94–110.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.