Education

Nudging Works to Get College Students to Seek Help

Nudges can connect students to resources and improve their performance.

Posted November 2, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Personalized nudges sent via email doubled college students’ use of campus support services and increased pass rates in developmental courses.

- Nudges to encourage resource use should leverage behavioral science, personalization, and two-way communication to the extent possible.

- Nudges should target specific behavioral outcomes and consider different barriers and opportunities by race, ethnicity, and gender.

- Nudges are most effective when paired with robust student support services, and services will be most utilized when paired with nudges.

Over the past decade, we in higher education have become increasingly aware of the financial insecurity many of our students face, leading to a proliferation of wraparound services on campus. For example, the College & University Food Bank Alliance estimates that over 700 colleges now operate food pantries… a 700% increase since 2012! But if it’s one thing behavioral science tells us, it’s that if you build it… people won’t come unless you increase awareness of it, de-stigmatize it, and remove behavioral and psychological barriers to access.

At Persistence Plus, we’ve nudged tens of thousands of college students to take advantage of food pantries, emergency aid, and other supports. So I was beyond thrilled to see The Hope Center release a new experimental study reaffirming that, in the words of Founder and President Dr. Sara Goldrick-Rab, "Nudging works."

Nudges Connect Students to Resources

Amarillo College (TX) operates the Advocacy Resource Center (ARC), a centralized hub that uses a case management approach to connect students with a food pantry, clothing closet, emergency aid, public benefits, counseling, and more. An earlier assessment by The Hope Center found that two-thirds of Amarillo students faced financial insecurity, yet only 13% used the ARC, with 80% of those students being women. This disconnect between students and resources is a nationwide issue: In 2018, for example, only 7% of CUNY students knew about Single Stop, and 40% never accessed any kind of support.

To remedy this utilization gap, The Hope Center tested email nudges that emphasized that the ARC is free to all—targeting students’ perceived ineligibility for services—and dispelled worries that using these services denies them to someone else in greater need (i.e., resource scarcity). One thousand Amarillo students who were in the lowest income quartile (≤ $20,000/year) or taking developmental education (which tends to predict financial insecurity) were randomly assigned to receive seven monthly, personalized nudges about the ARC; nearly 1,000 control students had access to the ARC but received no additional information.

Over the next year, 56% percent of nudged students visited the ARC, compared to 22% of control students. A year later, the difference was still nearly double (27% vs 15%). Moreover, nudged students used three times as many ARC services, and their pass rates in developmental courses were significantly higher (71% vs 59%). Not all of the study's intended outcomes were achieved, however. Despite aiming to close the gender gap in service usage, nudges appeared to have an even stronger impact on women’s use of the ARC. Moreover, nudges showed no downstream effects on general pass rates, GPA, retention, transfer, or graduation.

Leveraging Nudging to Support Students’ Basic Needs

This study, which achieved remarkable results with only seven nudges, merely scratched the surface of what nudging can do. If you're thinking about nudging students toward your campus support services, here are four lessons from my experience that can help you build upon the foundation laid out by the current research.

#1. Use more behavioral science tools. There are myriad reasons why students don't take advantage of resources, and each may be addressed by a different behavioral science tool. For example, some students attach shame to using a food pantry; this may be especially true for men who feel pressure to be self-reliant and effective providers. A useful nudge to combat this feeling is social norming. For example, many colleges have built or relocated their food pantries in visible, high-traffic areas. This not only makes it easier to find, but seeing similar students bustling in and out with bags full of groceries norms the behavior and alleviates stigma. At Persistence Plus, we’ve used social norms language in text messages that have increased pantry usage up to 45%. You can also consider nudges such as self-affirmation or expressive writing that help students process negative feelings elicited by help seeking.

#2. Go deeper with personalization. The Hope Center nudges included students’ first names to capture attention, but were otherwise agnostic to gender, whether students were new or returning to Amarillo, and which services they were eligible to receive. One way to further personalize nudges is to leverage data you already have. For example, an experiment we conducted at three community colleges used summertime enrollment data to specify whether students received nudges designed to help with re-enrollment or prevent “summer melt.” This approach led to a significant, 7-point increase in fall re-enrollment. Colleges seeing equity gaps in resource usage should strive to identify the unique barriers to access for each group and nudge accordingly.

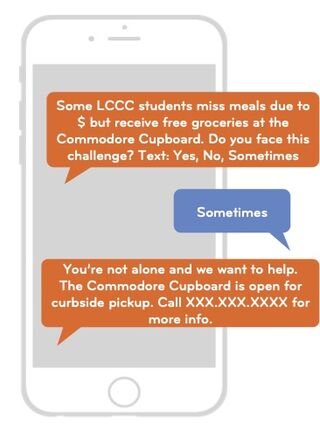

#3. Get students talking. The Hope Center focused on two barriers to ARC usage, perceived ineligibility and resource scarcity. While these nudges motivated over one-third of students, they failed to get several hundred other students in the door. Nudges that encourage two-way communication can help you identify students’ specific barriers, relay targeted information that is easier for students to retain and use, and gather insights for making on-campus changes. For example, asking students to share their roadblocks in administrative processes has allowed us to help colleges rethink enrollment, registration, and graduation bottlenecks.

#4. Design for the outcome you want to see. The Hope Center designed nudges to drive students to the ARC, which was highly successful, and had the additional benefit of increasing pass rates in developmental education. However, I wasn’t surprised they didn’t see further gains in terms of academic performance or persistence. Although targeting students’ basic needs surely helped, these are multi-causal outcomes for which addressing one challenge is unlikely to move the needle. Nudges are most effective when directly tied to your desired outcomes and student population. For example, we developed nudges based on self-affirmation and utility values interventions to motivate community college allied health students to return during the pandemic. Our experimental test of this approach showed an increase in fall 2020 re-enrollment among stopped-out students of over 13 percentage points.

Nudging is a powerful tool in the fight against poverty, inequity, and other systemic barriers to student success. But these nudges will lead nowhere without student- and equity-centered resources available on campus, as exemplified by Amarillo’s ARC. Low-cost, evidence-based, and scalable nudges complement these larger investments so that they can have the greatest possible impact on students. Without an effective nudging strategy, too many students in need of help will stay away, continue to struggle, and ultimately drop out.