Health

When (and Why) We Hide Infectious Illnesses From Others

We often hide our sicknesses from others, research finds—even contagious ones.

Posted March 27, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Have you ever hidden the fact that you were sick with a contagious illness from people around you? Perhaps you stifled a cough while attending a job interview or neglected to mention your scratchy throat during a first date you had been looking forward to. Maybe you even assured people sitting next to you at dinner that your runny nose was “just allergies.”

If you admitted to any such concealment behaviors, you certainly are not alone. In research conducted with my colleagues (Soyeon Choi and Dr. Josh Ackerman) at the University of Michigan we find that around 75 percent of our adult participants in the United States reported covering up their illness from others. How can our psychology help us understand why disease concealment is such a prevalent behavior?

The Sickness Psychology of a Social Species

Across the animal kingdom, being sick is typically not a recipe for social success—lobsters physically distance themselves from those infected with viruses while vervet monkeys exhibiting signs of fever are often physically assaulted by their groupmates. From a survival standpoint, this makes sense: Animals that freely frolic with the overtly infected risk contracting illness (and may die), while those with a propensity to identify and avoid sick others may be able to avoid illness (and survive).

From the perspective of a sick animal, then, it may therefore be beneficial (to the extent they don’t want to be physically excluded or beaten up!) to downplay any possible signs of infection. There is some evidence that this is the case: When zebra finches are infected and placed in isolation, they exhibit a typical set of behaviors associated with illness—lethargy, decreased appetite, etc. But when infected finches are placed in a social colony, their behavior suddenly is indistinguishable from a healthy finch.

Humans, too, tend to be disgusted by, physically avoid, and even forcefully isolate others who appear to be infected in attempts to mitigate the transmission of infectious illness. Alongside evidence from other social species, it’s not a stretch to think that an undergraduate attending their first party, a medical resident during an overnight shift, a maid-of-honor on a bachelorette weekend, or simply anyone with our diverse set of social goals may similarly take steps to avoid negative outcomes.

Indeed, in our studies of both healthy and sick adults, we asked 4,110 participants about their past, present, and future concealment behaviors. Our participants included healthcare employees (of which 61 percent reported past concealment), undergraduate students, and adults recruited online.

When we asked people why they concealed, people largely listed social (and often self-interested) reasons, from boarding planes to seeing patients, attending class to hanging out with friends. Interestingly, surprisingly few participants listed explicit institutional policies (like a lack of sick leave at work) as drivers of their concealment behavior.

To us, this suggests strong social motivations for concealment exist—and it may take more than just reevaluating institutional policies around sickness to curb concealment behaviors.

The Role of Illness Harm in Concealment Behaviors

People tend to be highly averse to harming others. Why then do we observe such high concealment rates, which presumably could lead to direct physical harm if others around you become infected?

In one of our studies, we asked participants to think about having an illness that varied on how harmful it was (that is, how contagious and severe). People thinking about harmful illnesses reported lower concealment intentions than mild illnesses.

This result suggests a cautiously optimistic picture of disease concealment: While concealment seems to be a common behavior, perhaps it is only the mild, less harmful illnesses that are being covered up.

Unfortunately, two final studies we conducted suggest this optimism may be misguided. We recruited people who were currently healthy or currently sick. For the healthy participants, we again had them think about illnesses that varied in how harmful they were to others, while for the sick participants, we asked them how harmful they thought their current illness was. Both groups then reported how likely they would be to conceal illness.

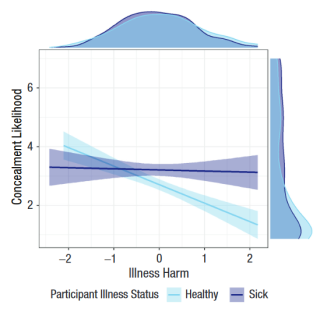

The three primary takeaways from these studies are visually represented in the figure on the left. First, like the previous study, healthy people reported lower concealment likelihood when thinking about more harmful illnesses (see the downward-sloping blue line).

Second, illness harm was not associated with sick people’s concealment likelihood (see the relatively flat purple line). In other words, people sick with mild illnesses were equally likely to conceal illness compared to people sick with severe illnesses.

Third, at high levels of illness harm, sick people were more likely to conceal than healthy people (see the difference between the purple line and the blue line on the right side of the figure, for instance at levels “1” and “2” of illness harm). This suggests that sick and healthy people make concealment decisions in different ways, with sick people appearing relatively insensitive to how harmful their illness is to others.

Significance and Future Directions

Together, these studies represent an initial step in understanding the prevalence and predictors of infectious disease concealment from a psychological perspective. We believe these results have important public health implications for how individuals and institutions manage the spread of infectious disease, especially during times of significant infectious disease transmission (like the COVID-19 pandemic).

A primary limitation of the studies we conducted is that our results may be somewhat limited to the population of participants we drew from: adults in the United States. It’s very likely that decisions to conceal infectious illness (or not) are strongly influenced by the culture one lives in—from how harshly people who violate social norms are punished to how commonly people get sick in a local environment. To this end, our team is currently collecting data from 22 different countries so that we can compare concealment patterns cross-culturally.

We are also interested in better understanding how harmful concealment behaviors are from a public health perspective. That is, how much faster does disease spread when there are 10 concealers compared to 100? We are assuming that concealing illness facilitates the spread of disease, but it would be valuable to try and quantify this spread.

Another question of practical importance is: What can be done to reduce concealment behaviors? Given the finding that sick people are insensitive to illness harm in concealment decisions, and the fact that over 40 percent of undergraduate students told us they misused a mandatory app-based symptom screener on campus while they were sick, it seems like solutions need to rely on more than just individual goodwill. These are both big questions with disciplinary ties to public health, epidemiology, and intervention science; we look forward to tackling these ideas in the future.

I’ll leave you with some final thoughts:

- “Should I be concerned about being surrounded by asocial, lying, psychopaths who don’t care if they get me sick?” Maybe, but I’d say no more so than before you read this article. Knowing that concealment is a common behavior can make it seem like concealers are all around you, but it also suggests that it’s a common experience to feel the pressure of needing to appear healthy in social situations. To me, this means we need to identify what is leading to these ubiquitous social pressures rather than identifying the concealers among us.

- “Is this just a COVID-19 phenomenon?” The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic presented a timely reason to conduct this research, but we don’t believe that the pandemic caused this phenomenon. In addition to indications of concealment-like behavior in other species like zebra finches, there’s ample historical evidence of human concealment behaviors across time, including during a bubonic plague outbreak in San Francisco. Further, in all our studies, we asked participants not to report on COVID-19-specific concealment, but rather to focus on times they have concealed other kinds of illnesses like the flu. We don’t think that disease concealment began, nor will it end, with COVID-19.

LinkedIn image: PeopleImages.com - Yuri A/Shutterstock

References

Merrell, W. N., Choi, S., & Ackerman, J. M. (2024). When and Why People Conceal Infectious Disease. Psychological Science, 35(3), 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976231221990

Behringer, D., Butler, M. & Shields, J. Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature 441, 421 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/441421a

McFarland, R., Henzi, S. P., Barrett, L., Bonnell, T., Fuller, A., Young, C., & Hetem, R. S. (2021). Fevers and the social costs of acute infection in wild vervet monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(44), e2107881118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107881118

Lopes, P. C., Adelman, J., Wingfield, J. C., & Bentley, G. E. (2012). Social context modulates sickness behavior. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 66(10), 1421–1428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-012-1397-1

Ackerman, J. M., Hill, S. E., & Murray, D. R. (2018). The behavioral immune system: Current concerns and future directions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(2), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12371

Crockett, M. J., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Siegel, J. Z., Dayan, P., & Dolan, R. J. (2014). Harm to others outweighs harm to self in moral decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(48), 17320–17325. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408988111