Relationships

Love Gone Bad—or Love Never Found?

Two ways you may be haunted by regret, and what they say about your choices.

Posted August 22, 2018

In a memorable scene from Goodwill Hunting, the counselor, Dr. Sean Maguire (played by Robin Williams), instructs young Will on the nature of regret through a story of how he missed a Boston Red Sox playoff game because he needed to talk to a girl he just met: “That's why I'm not talking right now about some girl I saw at a bar twenty years ago and how I always regretted not going over and talking to her. I don't regret the 18 years I was married to Nancy. I don't regret the six years I had to give up counseling when she got sick. And I don't regret the last years when she got really sick. And I sure as hell don't regret missing the damn game. That's regret.”

Is your most significant regret in life an action you performed or something you failed to do? It might be the purchase of an expensive house that turned in to a money pit over time. Or it could be the house of your dreams that got away because you were too slow in making an offer. Psychologists have found that people experience the biggest regrets in life for education, career, romance, parenting, the self, and leisure.

The Many Faces of Regret

Regret is an unpleasant emotional state that usually includes feelings of sadness and disappointment over negative outcomes or opportunity loss. A voluntary action that results in regret and psychological pain is considered an “act of commission.” An “act of omission,” on the other hand, can motivate feelings of regret when we have done nothing – no deliberate action or commitment – but later we feel like we should have.

Regret in the Lab vs. Real-Life

Researchers have documented a curious inconsistency between “experimental regret” and what people say about “everyday regret.” This additional layer of information underscores the point that we experience regret differently depending on the ecological features of our situation.

When reflecting upon the past, people often say that they regret the things that they have not done in life (e.g., talked to an attractive person, gone skydiving, taken an extra week of vacation etc.). Laboratory data suggest just the opposite – that people regret acts of commission that have negative outcomes more than acts of omission that have negative outcomes. Most of us would feel distressed over losing out on a lottery jackpot after we had changed our numbers from the winning combination to some other pick. It would probably be better just to lose with our first pick than to second guess why we made that move.

The best way to work through the issue of regret is to mentally simulate different scenarios:

“How will I feel if I get out of this relationship, but nothing in my life gets better?” and “How will I feel if I stay in the relationship but nothing gets better?” Psychologists found that students who adopted a “switch strategy” in a Let’s Make a Deal game show experiment and then lost experienced more regret and psychological pain than those who stayed and lost. In other words, I am going to go with my initial hunch and not change my answer. Similarly, some students experience this when they change their answers on a multiple choice test only to learn afterwards that their initial hunch was correct.

What can we learn about regret from Monty Hall?

Prior to the most recent reincarnation starring Wayne Brady, the original version of Let’s Make a Deal hosted by Monty Hall was a successful television program for over 25 years because the rules were uncomplicated and the prizes were deceptively easy to win. The game show posed a frustratingly simple dilemma to contestants: stay with your initial guess or switch to another option. Aside from Hollywood embellishments, like offering cash to influence choices and encouraging audience members to dress in outrageous costumes, the format was relatively straight forward.

Monty Hall, a thoroughly honest game show host, has placed a new car behind one of three doors. There is a goat behind each of the other doors. “First, you point toward a door,” he says. “Then I’ll open one of the other doors to reveal a goat. After I’ve shown you the goat, you make your final choice, and you win whatever is behind that door.” You begin by pointing to a door, say door 1. Monty, knowing full well what is behind all the doors, shows you that door 3 has a goat. What will your final choice be? Stick with door 1? Or, Switch to door 2? Of course, it is assumed that you desire the car, not one of the goats.

Don’t stick with your first choice—the best solution is to switch:

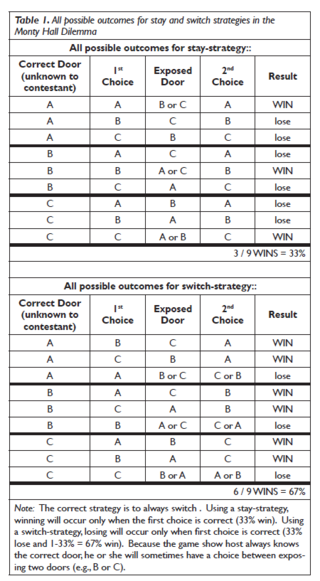

The correct strategy, if you want to win the car more often than not, is to always switch doors! This is counterintuitive, but correct. For a detailed description, see the included illustrations. The probability of winning under the stay-strategy is .33. Only when the initial choice is correct can a player win under this strategy. Many people think that a switch-strategy will not improve chances for winning, but it does. The initial pick is always random (door 1, 2, or 3), but the information the host reveals about one of the other doors is not random. The switch-strategy essentially minimizes the chances of losing because a loss will only occur when the initial choice is correct (33% of the time this will be true). Thus, a switch-strategy will produce a win 67% of the time (1 - .33 = .67). Table 1 provides a list of all possible outcomes under both strategies and demonstrates that the switch-strategy doubles the probability of winning the prize.

Looking Back, Moving Forward

Overall, research on regret shows that it is a reflection of where in life we see our largest opportunities for real growth and change. Will Hunting, played by Matt Damon in the film, was able to work through intense regret and begin thinking about his future with the assistance of his counselor. Many of us, like Will, can benefit from re-evaluating relationships, both good and bad, with friends, lovers, and ourselves.

References

Bennett, K. L. (2004). How to start teaching a tough course: Dry organization versus excitement on the first day of class. College Teaching, 52(3), 106.

Bennett, Kevin L. (2018) "Teaching the Monty Hall Dilemma to Explore Decision-Making, Probability, and Regret in Behavioral Science Classrooms," International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Vol. 12: No. 2, Article 13.

https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2018.120213

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Chen, S. (1995). Commission, omission, and dissonance reduction: Coping with regret in the “Monty Hall” problem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 182-190.

Roese, N. J., & Summerville, A. (2005). What we regret most... and why. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(9), 1273-1285. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1177/0146167205274693