Bias

The Confirmation Bias of Wordle Fans

No, the New York Times did not ruin Wordle.

Posted March 17, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Even supposedly harmless misinformation can be detrimental because it undermines good critical thinking.

- When the New York Times bought Wordle, many fans jumped to the false conclusion that the game got harder.

- A perception that the Times makes other difficult games may have led to confirmation bias.

In October, 2021, New York-based Welsh engineer Josh Wardle launched the deceptively straightforward Wordle, a word-guessing game that he invented for his partner, Palak Shah. Within months, it became a viral international phenomenon – a kinder, saner communal pandemic passion, perhaps, than the early Netflix Tiger King craze.

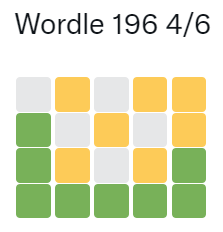

Specifically, it was in November, 2021 that Wordle’s player base began its jump from just 90 users to millions, in large part due to Tweets from a network of self-described “word nerds” in New Zealand. (Fun fact: It was one of these New Zealand word nerds, Elizabeth S., who created the colorful green and yellow emoji grid that has wall-papered Facebook and Twitter feeds for months. Wardle added it to his software later.) Wordle spiked next in Australia, then the UK and Canada, and the rest is history – a history that eventually included the seven-figure sale of the game from Wardle to the New York Times.

And that’s when the misinformation started.

False Accusations That The New York Times Ruined Wordle

No sooner had Wordle migrated to its new platform than news articles and Twitter users alike lamented that the Times had “ruined” the game. One Twitter user, for example, wrote: “The past few days of Wordle have had a different vibe. Seems like those choosing the words are actively seeking uncommon letter combinations in a way that wasn’t happening before.” Another tweeted: “new [W]ordle is getting pretentious?” And these users were far from alone in their perception of the supposedly newly tricky Wordle.

The Times actually had made changes, but they did not make it harder. In fact, as of mid-Feburary 2022 the Times team has not added a single word to the game. All they did was remove a few words that were obscure (like FIBRE or PUPAL) or potentially offensive (like SLAVE or WENCH). In one early example, AGORA was changed to AROMA. If anything, the Times has made Wordle easier. Moreover, The Verge pointed out that Wordle always had some tricky words like TAPIR, REBUS, and PROXY. And there have been many easy ones since the Times took over – like THOSE and FRAME. As The Verge reporter explained: “While the recent streak of tough words is definitely a thing (including today’s puzzle, which, I’ll admit, took me all six guesses to solve), it’s not because The New York Times is ruining the game.” (A quick search by date suggests that The Verge reporter struggled that day with CYNIC.)

The Confirmation Bias of the Wordle Fan

Why did so many people jump to a conspiracy-tinged conclusion about Wordle? Mashable suggested it may be due to our preexisting belief about the Times as “a sophisticated paper with notoriously difficult puzzles to solve. So, when [the Times] bought Wordle and began hosting the game on its site, and you had a difficult time solving one of the words, you might assume it's because of Times' zeal for difficulty.” In other words, this seems to be a classic case of confirmation bias. Confirmation bias occurs when our preexisting beliefs motivate us to pay attention to and remember evidence that fits with those beliefs and ignore evidence that does not. So you remember stumbling over ULTRA, but forget that you solved THOSE in three guesses.

You might wonder why we’re writing about Wordle conspiracies at a time when so much mis- and disinformation has dire – even fatal – consequences. But it’s important to hone our critical thinking skills in situations where we don’t have the same emotional connection as we would in, say, a geopolitical context. For example, we wrote about misleading animal photos early in the pandemic – another example of “fun” or “light” misinformation that seems harmless, but can actually be harmful. It was fun to believe that swans had come back to Venice as the tourists disappeared. Unfortunately, falling for this fun story opens us up to falling for more dangerous ones. We must work to be aware of our confirmation biases and ask good questions especially when we are motivated to believe something. And it’s easiest to practice this when the stakes are low.

As for the Times, will it remain a force for Wordle good? The paper itself calls the game “charmingly analog.” Observing the protectiveness of its fans, it has promised to leave it unchanged and, at least “initially,” free. As Wordle fans ourselves, we hope that is not misinformation. We are currently motivated to believe them.