Cognition

Tom Cruise, Deepfakes, and the Need for Critical Thinking

As deepfake videos proliferate, we need to think critically about what we see.

Posted March 21, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

- Photos and videos can be especially persuasive forms of communication, even when they depict a fake situation.

- "Deepfakes," false photos and videos created with the help of AI, are making it easier than ever to mislead with images.

- The threat of deepfake technology calls for more critical thinking about online media.

Who else has that one friend who replaced the heads of Adam Driver and Lady Gaga in the retro-cool après-ski shot from their film, House of Gucci? And who hasn’t seen Bernie Sanders in his iconic inauguration mittens and mask added to a friend’s pre-pandemic vacation photos?

We know from psychological science that photos are more persuasive than text (e.g., Seo, 2020), and we previously wrote about the need for skepticism regarding photos. In that post, we explored images presented out of context to convince viewers that, say, they were seeing swans in Venice after the calm of the pandemic. But the swans weren’t actually in Venice after all. Of course, most of us know how easy programs such as Photoshop have become, so we have become more skeptical of photos that seem a bit off. We are increasingly likely to check sources or even do a reverse-image search. This is a huge win in the fight against misinformation. Of course, misinformation continues to find new forms.

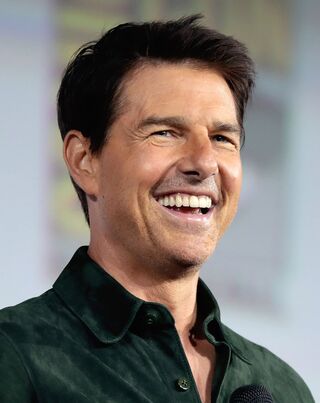

Enter the deepfake. Named for the deep learning that artificial intelligence makes possible along with, well, the word fake, a deepfake is a video (or sometimes a photo) so expertly created that it’s almost impossible to discredit. In fact, deepfakes were originally created for porn videos and have been used for revenge porn. They have been around a while, but deepfakes burst into mainstream consciousness with a trio of TikTok videos purporting to show Tom Cruise golfing, performing a magic trick, and telling a dumb joke about former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Nope, none of them are real.

The Threat Posed by Deepfakes

This doesn’t just happen to the Tom Cruises of the world. We’ve already mentioned the devastating practice of revenge porn, and there are numerous variations on it. Recently, in a storyline out of a twisted version of an '80s movie, a high school cheerleader accused a rival’s mom of creating deepfakes of her naked and drinking alcohol with the intent of bullying her into quitting the cheerleading team. The distraught cheerleader, Madi Hime, explained “That’s not me in the video,” and added that “I thought if I said it, no one would believe me because obviously, there’s proof, there’s a video—but obviously that video was manipulated." But what is obvious to Madi, who knew which images of herself were real and not real, is not necessarily obvious to all of us. Fortunately, Madi’s claims were backed by forensic evidence that connected the deepfakes to the cellphone of Raffaela Marine Spone, her rival’s mother.

Unfortunately, we don’t all have the powers of law enforcement to investigate the images we see. Apparently, it is technically possible to suss out which videos are real and which ones are fake, but it’s probably not something most of us can do. Researcher Hany Farid and graduate student Shruti Agarwal pointed out to a reporter a couple of clues that could have been noticed: “In one [of the TikTok videos], in which Cruise seems to perform a magic trick with a coin, Cruise’s eye color and eye shape change slightly at the end of the video. There are also two unusual small white dots seen in Cruise’s iris—ostensibly reflected light—that Farid says change more than would be expected in an authentic video.” Would you really notice either of these things? Well, we didn’t!

Researchers Cristian Vaccari and Andrew Chadwick (2020), citing the “power of visual communication,” worry that deepfakes are going to make us all more cynical and distrustful of news, especially from social media.

What We Need to Do

Widespread cynicism is not inevitable, though, especially if this idea reaches a critical mass of people: Think critically about every image and every video. Ask good questions about the site that is publishing the images or videos, the citations and sources behind them, and any possible agendas that the creators might have.

From a psychological perspective, images and videos are more compelling than text. But that’s exactly why we should push back and ask more questions! I mean, would Tom really put out a TikTok magic trick video?

References

Seo, B. K. (2020). Meta-analysis on visual persuasion–Does adding images to texts influence persuasion? Athens Journal of Mass Media and Communications, 6(3), 177-190. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajmmc.6-3-3

Vaccari, C., & Chadwick, A. (2020). Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Social Media + Society, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120903408