Free Will

Free Will Is Real and We Can Lose It

Our experience of conscious decision-making is not an illusion.

Posted April 13, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Previous studies seemed to suggest that before we make a conscious decision to do something, the unconscious brain has already decided for us.

- New research suggests that consciousness does indeed have "causal power," meaning that the experience of making a choice is not an illusion.

- Conscious control and regulation is a function associated with the prefrontal cortex and the "global workspace" that emerges from it.

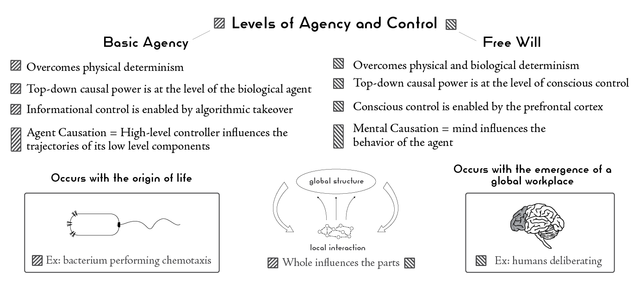

Making sense of free will in a physical reality requires a discussion that references physics, biology, and psychology, but we have already done most of the heavy lifting. In my last post, Finding the Freedom in Free Will, we learned that there are two types of causation in the world: bottom-up and top-down.

“Bottom-up” means the particles that organisms are made of at bottom do all the pushing around. You can imagine the evolution of the universe as tiny pool balls bouncing around and knocking into each other, such that the chain of causation is like a set of dominoes falling—there is no room for any influence by phenomena like agents or minds. There are only atoms following fixed trajectories specified by a relatively simple equation. Despite the feeling of agency, you don’t decide what you’re having for dinner tonight—a chain of physical events at the level of particles is what underlies the choice. Actually, there was never any decision at all, just a predetermined set of events. According to this paradigm, choice is an illusion.

“Top-down,” on the other hand, means that nature’s causation is much more complicated. When sufficiently driven by flows of energy away from thermodynamic equilibrium (a state of uniform disorder) toward a state of organization, a group of interacting organic molecules may come together to form an adaptive system. When these types of systems emerge in the universe, the “whole” constrains the “parts,” and the global patterns of configuration start pushing particles around.

Top-down causation—when information starts steering complex systems away from the trajectories determined by classical mechanics—frees systems from physical determinism, but agents still seem to be shackled by the constraints of biological determinism. That is, we often do what our genes or brains instruct us to do without reflection or deliberation. You can even see this hinted at in Sara Walker’s description of top-down causation through informational control, which gives life “the ability to harness chemical reactions to enact a preprogrammed agenda, rather than being a slave to those reactions.”

If an agent’s behavior is “preprogrammed,” it is hard to see how this is truly “free” behavior. The bacterium performing chemotaxis will reliably swim toward chemical energy and away from toxins. Its behavior is predictable and executed without any hesitation, so the process does not appear to involve any contemplation or reflective thought.

We’ve explained how agents act as causes, but that doesn’t seem to be sufficient for “free will,” since automatic behaviors work like reflexes. Another type of top-down causation—what we may call mental causation, or more specifically, conscious causation—is one step above basic agency, and would refer to the ability to override predetermined behaviors, which are all those programmed in genetically, as well as those that have been learned and encoded in the brain as procedural memory. Most of our actions don’t require deliberation, so it is really movement driven by reflective thought that we are talking about when we refer to free will.

But before we can explain free will, it is necessary to discuss the experiments that convinced many scientists that it doesn’t exist.

The famous “free will experiments” conducted by Benjamin Libet in the 1980s suggest that what feel like conscious decisions may have already been decided for us. In these studies, participants were instructed to choose when to move their hand and to record the exact moment in time they believe the choice was made. The neural activity corresponding to this response revealed that the feeling of voluntarily choosing to act is preceded by a spike called the readiness potential, which could be used to predict in advance when the movement would be executed. It would appear that before we make a decision, our brain has already decided for us.

This implies that we don’t really have conscious control over our behavior—we are passive viewers in a theater, along for the ride but unable to steer the ship. Our programmed movements may not be the result of purely bottom-up causation—we are still informational agents with causal power—but we would seem to be automatons acting according to a predetermined set of coded instructions. Consciousness would be epiphenomenal, which means it is a useless byproduct of the brain with no ability to affect anything, like steam being generated by a locomotive's engine.

The results of the Libet studies have been misinterpreted as proving that “neuroscience has debunked free will.” First, even if the decision to act is made by the unconscious mind, the movement can be inhibited or altered by the conscious mind. In an article published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies in 1999 called “Do We Have Free Will?” Libet himself stated:

“The volitional process is therefore initiated unconsciously. But the conscious function could still control the outcome; it can veto the act. Free will is therefore not excluded. These findings put constraints on views of how free will may operate; it would not initiate a voluntary act but it could control performance of the act.”

This explanation is consistent with a model of the mind as a multilevel (hierarchical) controller. If you can only do what is programmed by the more primitive brain networks, that would not be very free. An agent becomes “free” from its hardwired agenda when another level of cybernetic control emerges in the brain that allows the system to analyze its own behaviors. In humans, this kind of control is associated with the prefrontal cortex—the region in the front of the brain responsible for higher cognitive function.

A healthily-functioning prefrontal cortex allows one to override their primitive instincts, to think rationally, and to respond to emotional or stressful events in a controlled manner. It does this by arming the conscious agent with a higher level of self-regulation, known as cognitive control or executive control. Free will refers to an agent’s ability to exercise control over a preprogrammed behavior that the high-level controller, the conscious mind that monitors an organism’s actions, determines to be maladaptive or suboptimal. Suboptimal behavior would be any behavior that is inconsistent with the agent’s long-term goals. An example can clarify the difference between behavior that is instinctual or reflexive and behavior that is regulated or controlled.

If you’re walking past a food truck and you’re starving, you might want to snatch that delicious-looking kabob and sink your teeth in, but as a civilized man or woman, you don’t do that unless you’re going to pay for it. But if we brought a caveman to an urban square with a time machine, he would likely have a very hard time keeping his hands off of food, and if he happens to be in a “red light” district, off of other things. To be civilized means being able to transcend your primitive brain and reflexive behavior, which is not typically going to produce the optimal response for a member of modern society.

But free will isn’t only confined to Libet’s “veto power.” In a 2019 study, Christof Koch and colleagues showed that when Libet’s experiment involves important choices, rather than arbitrary ones—like when to move one’s arm—the readiness potential disappears completely. While arbitrary decisions are aimless and without consequence, deliberate decisions are those that have practical or moral consequences:

“We directly compared deliberate and arbitrary decision-making during a $1000-donation task to non-profit organizations. While we found the expected readiness potentials for arbitrary decisions, they were strikingly absent for deliberate ones…challenging the generalizability of studies that argue for no causal role for consciousness in decision-making to real-life decisions.”

Again, these functions—like deliberation and planning—are associated with the prefrontal cortex, and something called a “global workspace,” which corresponds to the attractor of neural activity that emerges out of the prefrontal cortex’s computational architecture. With a sufficiently-sophisticated global workspace comes the power of imagination, which allows us to play with the mental model of the world that evolution and adaptive learning have built up over time. We can travel back and forward in time in our mind, and this allows us to plan for the future.

So, conscious agents with the ability to imagine can control their own destiny by selecting the future that is consistent with their long-term goals from a menu of possible options. Philosophers call these alternative futures “counterfactuals,” and when we become aware of them, we must then pick the particular path we take out of the space of possibilities. It is in this act that we find the freedom in “free will.”

One way we can be sure that free will is real is that you can lose it—and this is a point that is of great importance to our justice system. If prefrontal cortex function becomes impaired, the high-level controller vanishes and the ability to regulate one’s behavior goes along with it. When this happens, an agent has less control over their patterns of behavior, and we see this with drug addicts who cannot override their tendency to do something that is clearly hurting them. The neuroimaging literature shows that cocaine and alcohol addiction impair networks in the front of the brain associated with executive control. As a consequence, addicts are more of a slave to their limbic system, thus “less free.”

We also see a loss of free will in psychiatric disorders where prefrontal activity is impaired. People with schizophrenia have reported feeling as if their movements are being directed by forces beyond their control. This could arise when the neural mechanisms associated with cognitive control dissolve, leaving an individual with only old brain structures that are executing wired-in programs.

A loss of conscious control may also explain the curious mental disorder known as Cotard’s syndrome. Those unfortunate souls experiencing Cotard’s delusion are convinced they are dead, and in some cases, starve to death because “the dead do not have to eat.” Unsurprisingly, fMRI studies show impaired activity in the prefrontal cortex, specifically in areas associated with cognitive control. The feeling of being dead might arise when a person feels like they have lost their causal power.

We have explained why humans have will that is as free as can be, but the idea of “conscious causation” will remain mysterious until we explain the mystery of consciousness. For that, we must get Gödelian, which means we must explain how the magic of self-reference brings the observer doing the controlling into existence.

This series of posts is adapted from my book The Romance of Reality: How the Universe Organizes Itself to Create Life, Consciousness, and Cosmic Complexity.

References

U. Maoz et al., “Neural Precursors of Decisions That Matter—An ERP Study of Deliberate and Arbitrary Choice,” eLife (October 2019), doi:107554/eLife.39787.