Emotions

Do Not Validate Unexamined Emotions

Emotions are clues to one way we experience our world.

Posted April 6, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Emotions are concepts that organize certain life experiences.

- Emotions tell us to reflect on our unique, historically-driven experiences that we may code as anger, fear, or hurt.

- You cannot validate an emotion without validating the personal experience that represents a given emotion.

It is popular to advise people that to interact effectively with another person, it is important to “validate” their feelings and emotions. It is said that doing so can facilitate good interactions because it tells others that you understand them and value their experience.1

However, there should be caution about this advice. Therapists, counselors, and helpers note that while you are validating emotional experience, you are not necessarily agreeing with what their emotion is about, nor that the emotion they are feeling is warranted.

My Concern With Validating Unexamined Emotions

As a psychologist who has worked for many years with couples, my interest is in the emotions experienced in interactions between people in intimate relationships and how to effectively deal with them.

I have three concerns about the advice to validate any emotional reaction without examining the personal experience of both people in each given interaction.

- How do you go about this—validate what someone is feeling yet not agree with what the feeling is about nor that it is warranted, i.e., that it is a “valid” reaction?

- When you validate feelings about an event, you stop the person from reflecting on the situation.

- The views of emotion that support this kind of advice are outdated.

An Example of an Emotional Interaction Between a Married Couple

Sarah and Lucas, who had been married a few years, were sitting together after dinner one evening when Sarah began talking about a difficult situation she had at work. Lucas, perhaps caught up in his own thoughts, did not respond to Sarah.

Sarah reacts emotionally with, “How can you ignore me like that? I work so hard to be nice to you!” Sarah is angry at Lucas, which justifies her accusing him of “ignoring” her. She adds a little zinger—she is so nice to him.

If Lucas were to “validate” Sarah’s anger, he would say something like “I understand your anger, but I didn’t ignore you.” Even if this response satisfies Sarah, it misses so much in this interaction that could be useful to this couple. Here’s the problem:

- Sarah “interpreted” Lucas’ silence as him “ignoring” her without crosschecking with him why he had been silent.

- Interpreting his silence as “ignoring” her implies he intended to be silent which justifies her anger.

- You cannot “validate” Sarah’s anger without also validating her unexamined take on the event

I will come back to how Sarah and Lucas can best work through this tricky situation in their marriage.

A New Theory of Emotions2

Let me introduce neuroscientist and psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett, who offers us a new way to look at emotions. According to the new approach, emotions (even the basic ones like fear, anger, sadness, happiness, and disgust) are not distinct entities inside us. Historically, emotions have been thought of as distinct categories of experience located in a specific brain area (e.g., the amygdala) and identifiable by universal facial muscle movements, bodily changes (e.g., increased heart rate), and your brain's electrical signals.

Feldman Barrett’s research found that no brain region is dedicated to any single emotion. Further, every emotional brain region is also activated during non-emotional thoughts and perceptions. There is no unique biological “fingerprint” for each psychologically identifiable emotion.

A New View of the Brain3

The older view that there are specific brain regions that are home to each single emotion does not fit with the newer understanding of the brain as a massive interacting network rather than an organ with distinct regions associated with different kinds of human functions like thinking, emotion, and action. This massive network is comprised of billions of communicating neurons, which can function in different ways at different times.

This massive computational network operates by organizing itself into what is a running "internal model" created by information from past experiences and from the internal workings of your body—your physiological status. These "internal models" are designed to predict what is about to happen and what the best action is to deal with the current event.

These "internal models" are organized by the way we consciously think about our experiences. We think in concepts, like the concept of emotion. These "internal models" thus are described as "embodied concepts."

Emotions are one type of embodied experience that is "constructed" by our encoded past experience organized around the names we give emotions—fear, anger, sadness, happiness, disgust, etc.

The Sensory Basis of Emotion Concepts4

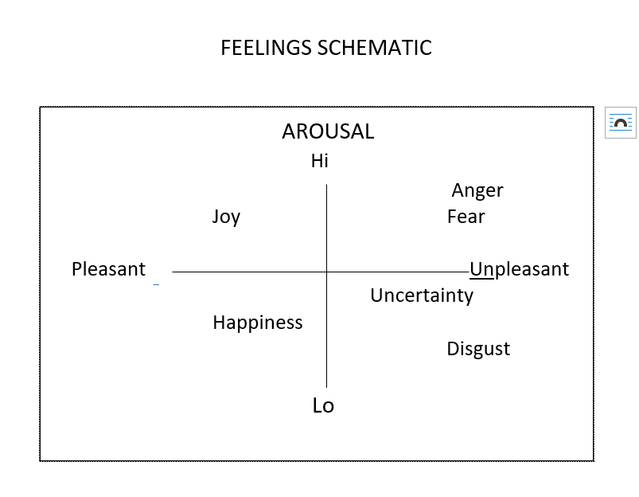

Our brains do come prewired to experience feelings, which are not emotions. You can have feelings like calmness and agitation, excitement, comfort, and discomfort. These feelings are ongoing monitors of what is going on. They represent changes on a continuum of arousal on one dimension and pleasantness and unpleasantness on the other hand; shown on the diagram below.

These “feelings” keep track of what is going on in your internal and external worlds. We use the term “affect” for this basic dimension of our experience. Our emotions, then, are our culturally determined overlays of this basic aspect of how we monitor our world based on our past experiences and in anticipation of how to act.

Re-thinking the Validation of our Emotions

Remember the idea that you can “validate” someone’s emotion without necessarily agreeing what their emotion is about, nor that the emotion they are feeling is warranted. This is misleading. When we “validate” someone’s emotion, we are validating their “take” on their current situation based on their own personal history. There is no such thing as validating an isolated “emotion” independent of the event in which it happens and your personal take on it.

Emotional Experience Calls for Self-Reflection, Not Validation

Let’s find out how Sarah and Lucas can solve the disruption in their relationship.

In the interaction described earlier with Sarah and Lucas, Lucas is likely to respond with something like, “I don’t know what you are talking about” because he doesn’t know how to respond to Sarah’s anger and her characterizing him as “ignoring” her.

Self-Reflection Is the Best Way for This Couple to Manage This Emotional Interaction

Being self-reflective means learning to be aware when you are angry (also known as annoyed, irritated, miffed, etc.), fearful (antsy, anxious, upset), or feeling hurt (which is a catchall feeling that doesn’t say very much). It means you recognize you need to step back for a few minutes to reflect rather than act on the emotion. Lucas’ surprised reaction to Sarah’s angry complaint is a clue to her to step back to ask herself, “Wait, Sarah, what’s going on—why are you so angry?”

Reflection allows your brain to pause during strong emotions to sort through what you are experiencing—to sort out the many interpretations of what is going on between you and the one you love. And, to sort out what is going on inside you. Reflection can inform your future reactions in face of high arousal and unpleasant interactions.

Resolving the Interaction

Once Sarah reflects on why she is so angry and why she characterized Lucas as "ignoring" her, she can recall how sensitive she is to not being attended to. This goes back a long way—often feeling as a youngster not listened to by her parents and other important people in her life. She often felt “ignored.”

Sarah can become aware of the ways she constructs anger when she interprets others as not paying attention to her. She can learn that her unexamined anger justifies her negatively characterizing her husband’s actions.

Once she reflects on her quick angry reaction to Lucas, she can think about whether or not he typically does not listen to her the way she wants. If this is the case, she can address this with him—but not by angrily accusing him of “ignoring” her.

What You Can Validate

What you want to validate in others and have validated for yourself is the physiologically encoded histories of your experiences around the emotion concept. It is the events of your life encoded by your emotions that are to be validated.

Lucas will want to "validate" Sara’s sensitivity around not being listened to. He can be aware that when she gets angry at him that it may not be about what he actually did, but her experience of what he did. This will help him not react but be proactive in talking with Sarah.

Emotions are indicators of the way we organize certain life experiences that are only understandable by reflection. It is the life experiences that we want to validate.

References

1. Salters-Pedneault, Krislyn PhD. “What is Emotional Validation?” VeryWell Mind/ April 26, 2023.

2. Barrett, Lisa Feldman. “The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 1–23.

3. Barrett, Lisa Feldman, 2017

4. Shariatmadari, David. “I’m Extremely Controversial: The Psychologist Rethinking Human Emotion.” The Guardian. September 25, 2020.