The teenage brain is like a person ready to bungee jump off a suspension bridge into a crevasse. Limbic logic gets you ready to jump, the thrill of the limbic rush propels you off the bridge, and we as adults just have to be sure the bungee cord is tied tight enough to bring the teenager back from the brink of a possible disaster.

Sometimes fear can paralyze the jumper, but sometimes that fear is a good thing! Other times the fear of being seen a particular way overcomes the fear of smashing several hundred feet below on your face, so saving face causes you to risk losing your face. The teenage brain wants to feel pleasure, take risks, and be social. An unfortunate set up for drugs.

I recently met Kefi,(not her real name) a 17 year old high school Junior after she had overdosed on several dozen pills of Klonopin, Ativan, and Xanax, all highly addictive anti-anxiety prescription medicines, along with a similar amount of Percocet and Vicodin, highly addictive opioid pain killers. The overdose had almost killed her, and were it not for a stay in the Intensive Care Unit of a very good hospital, she could easily have died.

She sat across from me in my office, her cropped bangs barely brushing the top of her eyebrows, looking serious and determined. Kefi told me somberly of her experience, insisting she was now ready to stop all drugs forever, regarding her revival as God’s way of giving her a second chance. She was now committed to a sober life, having first been committed to an inpatient psychiatric hospital where she had been transferred after being deemed medically stable enough to leave the ICU. There she had spent a week on a locked psychiatric ward, unable to leave, unable to go to the bathroom without permission. The experience was eye-opening as she described other teenagers much, much more impaired than she.

“Some of them were crazy! A bunch had even tried to kill them-selves on purpose,” she remarked incredulously. “At least I didn’t do that.”

“No? Taking all those pills wasn’t trying to kill your-self?” I asked during our first meeting. “What happened?”

The story I am about to tell you is true, one of many which after hearing I wonder, what were these kids thinking? And then realize in some ways they weren’t. Of course, we are always thinking, wondering, but not always planning or anticipating the consequence of our actions. This is especially true in adolescents, a function of the differential maturity of the brain. The question in this regard is less “What were they thinking?” as, “What were they feeling?”

My patient had planned on sharing. This virtue taught in pre-school had unfortunately extended to her current set of friends, many of whom were using drugs and alcohol like her. It was Friday, and the weekend beckoned intriguingly. Kefi carried in her pocket the little baggie full of Klonopin, and Ativan, and Xanax, and Percocet and Vicodin, absolutely ready to distribute them freely to her three best friends and the four of them were going to go somewhere after school and get high. In this one event her teenage brain was going to do the three things it wanted: to feel pleasure, take risks, and be social.

This was new drug territory for Kefi. Even as a minute before she had somberly told me of her intent to be sober, the memory of the anticipated moment surrounded her voice with a cadence of exuberance. (This is not uncommon when listening to the drug stories of my patients, but does not exclude their desire for sobriety. Most of them are just hours away from having used, and the deep dopamine drive is not yet fully at bay. But in their heart of hearts they want to be sober. Unfortunately, addiction does not happen in the heart. It happens in the brain.)

Having no idea of the effect, however, or how long it would take to work, Kefi took two or three pills on her way to school, with the intent of sharing the other 30 or so with her friends. She didn’t really feel anything for a while, but her teachers seemed to notice a difference. In fact, when she started to fall asleep in class one of the teachers took Kefi down to the Principals office, fairly sure her student was doing drugs.

Kefi sat in the waiting room of the Principal. Her voice changed from the euphoria of using to the anxiety of discovery. She was about to get in serious trouble. “I started to think Dr. Shrand, I mean really think. If I got caught with drugs on school property, especially like a baggie full which looked like I was trying to sell the stuff, I was going to get expelled. Poof. There goes college and I’m a Junior and I have a plan to go to like The West coast. So I started to get a little panicked.”

And now comes that amazing moment where I listen to a brain caught in the developmental turmoil where impulses emerge before a well formed thought. Kefi had a baggie full of pills. She had to get rid of them. Having a positive drug screen, if they did one, would perhaps get her a suspension, but more likely a warning. She was a good kid, and had never been in drug trouble before. But getting caught with pills would nail her. So Kefi decided to flush them, get them out of sight once and for all.

But instead of flushing them down the toilet, Kefi flushed them down her esophagus. As she sat in the waiting room, with a water bubbler just outside the door in the hall, she surreptitiously pulled the baggie out of her pocket, deftly emptied the contents into her hand, threw like seeds the pills into her mouth, and as she got up to go to get a drink from the bubbler shoved the barren baggie back into her pocket.

“What were you thinking?” I asked, with a trained inflection in my voice, designed to present an image of slapping your forehead with the palm of your hand as you wonder just that. “You could have died from all of that.” I added with all the aplomb of a Captain Obvious!

“I know, I know,” she said in astonishment and agreement, without a shred of impertinence. “But I really wasn’t trying to kill myself. I just didn’t want to get into trouble.”

Ok, so this is where I have to stop and scratch my head. Here is such a wonderful example of the immediacy of thought inherent to a teenager. Despite their growing ability to abstract, to write poetry, explore the nuance of American History, or learn a language, their brains in part are still all about here and now. I don’t want to get in trouble now, not even considering that taking all those pills could kill her. This absolutely was not a suicide attempt. This was the pre-frontal cortex of the brain succumbing yet again to the impulse driven limbic logic: Of course it made sense to take all the pills. Kefi had to get rid of the evidence!

Knowing how the brain works is not an immunization for my constant amazement at how the brain works. Kefi is not a stupid girl. She will get to college, and have the grades she needs to be competitive at very good universities. Taking the pills is not about stupidity. But it is about the danger inherent to the three loves of being a teenager: wanting to take risks, wanting to feel pleasure, and wanting to be social. All three were at play with Kefi and the pills, but, as she said herself, “No way did I want to die.”

Kefi was bungee jumping. Any teenager could be a Kefi. Perhaps not taking an accidental overdose, but by taking an action that may make an adult scratch their head and say what were they thinking? Why on earth would she take such a chance? How did her fear of being caught outweigh the fear of dying from an overdose of pills? Was it fear that gripped her limbic system: the fear of being seen a certain way, so intolerable, that her only choice was to get rid of the evidence? Now. Immediately.

The adolescent makes decision based on past experience, which is limited but attributed to the current situation. (Unfortunately, how can anyone know their experience is limited when they are an omnipotent teenager, intoxicated by the growing awareness of who they are?) Perhaps a much younger Kefi was about to be caught by her Mom having taken an unauthorized cookie, and quickly swallowed it to get rid of the evidence. Perhaps at another time she had been in a situation where she was scared and hid to avoid a danger, rather than run away or try to fight. Perhaps she had simply been so overwhelmed with fright of being caught by the principal that her thoughts turned simply to survival of this moment only, not of the moment five minutes from now.

So Kefi swallowed the pills. And almost died as a result. She jumped off the bridge, and we, the adults, were the cord that tethered her. It was an adult that recognized she was drugged on something. An adult that called the ambulance. An adult that drove her to the hospital. An adult that triaged her, lavaged her, intubated her, got her to the ICU, saved her life. Many, many adults were the bungee cord, bringing back this teenager from the precipice of a deathly jump off a bridge from which she need never have propelled herself. Bungee jumping.

But to bungee jump and survive one has to use a cord, which stretches and recoils, pulling you back up to the top of the bridge, then relaxing and contracting as you bounce up and down. In many ways, we adults are the cords. We adults are meant to have outgrown the vagaries of development, enjoying the maturation of ability to curtail that lusty limbic logic with a cortical cognition of consequence: an appreciation that actions do indeed have outcomes. But we have to practice what we preach. We must be cautious not to judge the adolescent, as our actions have consequences as well. How we become that bungee cord for our kids will have an influence on the brains of our teens. How they perceive our perception of them has incredible impact. Do we want to perpetuate the limbic logic by shouting, but going limbic ourselves, or model mindfulness and cortical control, helping our kids understand the dilemma they face through no fault of their own but simply as a result of evolution? We need to keep it frontal and not go limbic.

Our new understanding of the teenage brain has got to be a part of how we develop our appreciation of the teenage mind. Their brains may not be their fault, but they are their responsibility. Kefi was indeed lucky, but how she now walks her path of sobriety will take more than luck. It will take careful guidance, a carefully tempered cord, not too constricting, not too loose, not umbilical but flexible for her to safely take her next jump: hopefully not to recoil into the world of addiction but instead rebound into a commitment to sobriety. No way did she want to die, and perhaps now she is ready to jump start her cortical cognition of consequence.

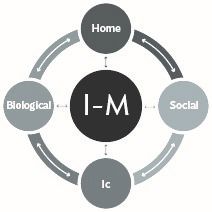

It's an I-M thing.