Environment

Taming Color

Part 3: While color excited some, many others saw it as a threat to be tamed.

Posted October 20, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

For much of human history, an individual’s access to color was limited to the colors that occurred in their natural environment. Rare pigments and dyes were expensive and beyond the reach of most people.

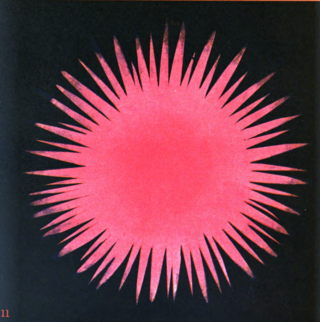

But in the mid-nineteenth century, the creation of the first chemical colors spawned a revolution in people’s access to colors. Suddenly, hyper-bright, cheap, and easily reproducible colors were available to people of all social classes, and the streets exploded with color.

Nineteenth-century commenters were simultaneously awed by the array of wondrous hues and appalled by the way color tore through their cities. They found the quantity of bright colors jarring and disorienting. For example, a Boston-based magazine noted that people could no longer enjoy leisurely walks through parks because women’s dresses were too bright and distracting.

The mass production of color fundamentally altered the way people experienced the world around them. While color was exciting, it was also seen by many as a threatening force needing to be tamed.

Color Chaos

At its inception, the dreamy new world created by color was, for many people, disorienting, chaotic, and uncomfortable. Even the people who loved the new brilliance seemed to sense that color (and its commerce) had somehow disrupted social order.

For color critics, the visual chaos of modern colors was like a disease, preying on people stressed out by modern life. The nineteenth-century writer Pierre de Lano warned, “Color…is a modern taste, born certainly of the nervousness that torments our imagination, the dulling of our sensations, that constantly ungratified desire, which almost tortures us and we apply to every aspect of our feverish life.”

Because color was no longer bound by prohibitive prices or sumptuary laws, it no longer indicated a person’s social status. In earlier eras, rare colors like purple connoted luxury, but suddenly, a duchess and a seamstress could equally afford brilliant purple gowns.

There was no more visible hierarchy, which, for members of the lower classes meant the promise of freedom, but for members of the middle and upper classes often signaled potential social disorder. In fact, some theorists like Albert Henry Munsell explicitly referred to the bright new world as “color anarchy”—demonstrating just how chaotic this new perceptual regime seemed.

Taming Color

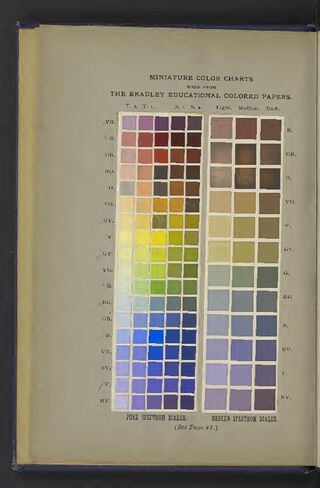

In light of color’s perceived dangers, many people—both consciously and unconsciously—tried to control color, give it order, and contain it. For example, thousands of artists, naturalists, manufacturers, philosophers, interior decorators, chemists, educators, and printmakers made it their top priority to come up with new rules about color.

During the nineteenth century, Europeans and Americans developed hundreds of new color systems, including most of the color theory that we accept today. They argued about the “science of aesthetics” and hotly debated which colors could be paired without becoming “barbarous.”

Color became a central part of education in order to place it, in the words of Milton Bradley, “on a broad and safe foundation,” and color innovators like Bradley and Louis Prang created new educational materials like construction paper and crayons.

In a previous post, I discussed another kind of “color taming,” prevalent in the nineteenth century: the spread of the idea that neutral colors were a mark of “good taste.” When bright colors no longer served to signify high social status, the discourse shifted 180 degrees. Once colors could be mass produced, “loud” colors quickly became a sign of bad taste, while genteel social elites insisted that muted palettes were more dignified.

You can still see the legacy of this chromophobia in many of our notions about work-appropriate attire, home décor, etc.

We accept many of these color-related ideas now as a kind of “second nature,” but their history wasn’t as simple as it may seem. In fact, our most basic knowledge—the things that we question the least—is where our deepest social and cultural values often lie. When something seems “natural” to us, it becomes a place that unarticulated assumptions and unthinking behaviors can easily hide.

Mass-Produced Color

When color was something natural and rare, it often took on the value of something sacred. Color was infused with a kind of magic, and medieval alchemists could only dream of the cheap, brilliant colors conjured into being by nineteenth-century chemists like William Henry Perkin.

Yet some scholars argue that once color was mass-produced, it lost its magic. Modern consumers tamed color so successfully that it essentially became meaningless. In the words of François Delamare and Bernard Guineau, “The very abundance of colors in the modern world seems to dilute our relationship with them. We are losing our intimate connection with the materiality of color, the attributes of color that excite all the senses, not just sight.”

The fact that so many of us have never truly considered just how saturated our lives are by mass-produced colors reveals that these scholars aren’t completely off the mark. It’s safe to say that most of us aren’t thrilled by the sight of glowing orange traffic cones, nor do our jaws drop when we see the array of paint colors available at the local hardware store.

It’s hard to imagine, but when the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries let chemical colors loose into the world, they weren’t meek creatures. People scrambled to tame color, make sense of it, and systematize it until, eventually, familiarity and new cultural norms diluted color’s power.

We cannot return to a world of pre-modern color, however, it’s worthwhile to take time to think about how special, wondrous, and powerful color can be. We can loosen the reins on color and stop trying to control it. We can allow it to regain a bit of its magic. (This beautiful essay by pigment forager Heidi Gustafson might help.)

Paint your walls without fear; wear the colors you want to wear; or at least, catch yourself when you start to criticize someone else for wearing or using a loud color. Revisit your “second nature” assumptions and let color run a little wild again.

References

Ballou’s Monthly Magazine (January 1882); quoted in Deb Salisbury, Elephant’s Breath and London Smoke: Historical Color Names, Definitions, and Uses in Fashion, Fabric, and Art (Abbott, TX: The Mantua-Maker Historical Sewing Patterns, 2015), 158.

Bradley, Milton. Elementary Color. 3d ed. Springfield, MA: Milton Bradley, Co., n.d.

Dry Goods Bulletin and Textile Manufacturer (March 6, 1886): 6; quoted in Regina Lee Blaszczyk, The Color Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012, 42.

Delamare, François and Bernard Guineau. Colour: Making and Using Dyes and Pigments. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000, 125.

Gustafson, Heidi. “Dust to Dust: A Geology of Color.” The Side View. June 5, 2019. https://thesideview.co/journal/dust-to-dust/

Lano, Pierre de. L’Amour à Paris sous le Second Empire (Paris: H. Simonis Empis, 1896), 182; quoted in Kalba, Laura Anne. Color in the Age of Impressionism: Commerce, Technology, Art. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017, 6-7.

Munsell, Albert Henry. A Color Notation, 1st ed. Boston: George H. Ellis, 1905, 76.