Bias

There’s Nothing Neutral about Neutral Colors

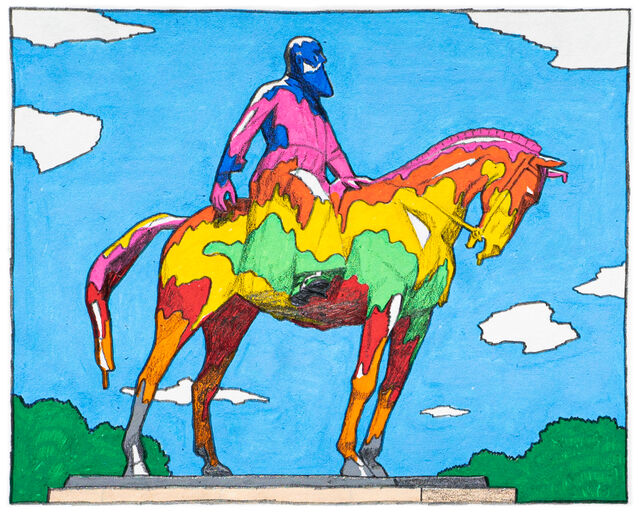

The vivid history of colonialism and chromophobia.

Posted June 16, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Would you paint your house a luscious purple? Would you drive a pink car? Would you dress head-to-toe in sunshine yellow? If you said yes, you’re in the minority.

That’s not because gray houses, white cars, and black suits are inherently appealing. Color norms and preferences have a deep history, and according to the art theorist David Batchelor, “In the West…color has been systematically marginalized, reviled, diminished, and degraded.” This marginalization of color has led to collective chromophobia, or fear of color.

Chromophobia has a complex past spanning millennia, but the age of Western colonial expansion put it on steroids. Over the course of the last few centuries, color became a powerful visual indicator of a person’s perceived social, intellectual, and racial status.

There's nothing neutral about neutrals. Read on to learn why we all need a little more color in our lives.

Chromophobia Is a Form of Control

Your initial objection to the concept of chromophobia might be that it’s simple to look around and see plenty of color: green trees, blue sky, vibrant flowers. None of these inspire fear.

But consider this: In the things that we make or buy, color tends to be reined in. (Note, when I say “we,” I’m speaking of a dominant American and European approach to color. Many cultures embrace color, as I’ll explore below.)

For example, it’s fashionable to wear a “pop” of color, but unacceptable for your average American man to show up to a business meeting in a hot pink suit. Large doses of vivid color can seem like an assault on the senses. It’s too “loud.” Too “tacky.”

Chromophobic societies don’t do away with color altogether. They control it.

Just think of all the rules we have for colors: pastels are for the spring; muddy green clashes with bold red; saturated orange is fine for a front door, but your homeowners’ association would shudder if the whole house were orange. All of us know what primary colors are and that red is “warm.”

These rules have become second nature to us, but they aren’t timeless. The concept of primary colors only emerged in the eighteenth century, and the idea of warm colors developed in the nineteenth. In other words, these rules are the product of a particular historical era. And in that era, people were highly concerned about the “anarchy” of color.

There are many reasons color was perceived as socially threatening (too many to cover here), but one major driver was colonial expansion.

The Empire of Color

As European countries extended their trade networks, some of the most precious commodities they found were pigments. Elites reveled in pricey, cochineal-dyed garments and lapis lazuli-dappled paintings.

But as expensive colors grew cheaper and more widely accessible, a lot of powerful businessmen put up resistance. For example, during the seventeenth century, the British East India Company started importing cheap, brightly colored cotton from India. The wool and silk guilds were afraid of losing their stronghold on the market, so they asked lawmakers for protection. New regulations stipulated that the colorful cottons couldn't be sold in England; they had to be immediately exported to other markets.

So, Europeans took their colorful wares to places that would treasure them. West Africans had been using cloth as currency for centuries, and early European merchants learned they could trade colorful cloth for slaves. Europeans took colorful textiles and pigments from places like India, Southeast Asia, and Mexico and traded them for African slaves, many of whom were put to work producing more dyestuffs, like indigo.

Between the late 1800s and the early 1900s, Western European countries aggressively expanded their claims on foreign lands. Previously, the goal had been to enslave Africans, but the new goal was to bring them into the consumer fold. European empires extracted resources (many of which were color-related), then traded them back to their colonial subjects for profit.

By tying chromophilic (color-loving) cultures together, Europeans built a highly lucrative and utterly exploitative economic system.

Superiority and Savagery

Meanwhile, back in Europe, people began associating bright colors with Other-ness, degeneracy, and inferiority. The German writer Goethe famously stated, “Men in a state of nature, uncivilized nations, and children have a great fondness for colors in their utmost brightness.”

That prejudice was still alive a century later. In 1912, the advertising executive Frank Parsons asserted, “Many Latin races, still somewhat primitive in taste, need [red] to meet their temperaments.” And in 1921, color psychologists like J.C.F. Grumbine still stressed, “The primary colors of red, yellow, and blue appealed to the elemental and simple minds of the savage.”

Some authors used pseudoscientific justification to support these claims. They argued that “savage” people needed stronger stimulation because they had duller senses. (This justification was also used by slaveowners who claimed slaves were “insensitive” to pain.)

Increasingly, so-called “good taste” became linked to “quiet colors,” or what we’d call neutrals today. For example, gentlemen only wore dark suits, and demure women never wore red. Over time, neutrals became the stamp of social and moral superiority, while too much saturation threatened a slippery slope back to “savagery.”

In short, color preferences became a weapon, a way to instantly label a person as “uncivilized” or inferior.

Let Go

The very idea of “good taste” draws on a deep well of cultural assumptions of what's “normal” or “refined.” There is no such thing as an inherently professional, respectable color. Those are categories that we’ve created, and frankly, they come with a lot of economic, social, and historical baggage.

It’s time to revisit those assumptions and loosen the reins. I’m not suggesting that everyone has to parade around in neon or toss neutrals out the window. But personally, I’d love to see a world that readily embraces color instead of restraining it. I’d like for us to overcome our collective chromophobia and say, “It’s okay to step out of my comfort zone! I’m going to have fun. Or, at least, I’m not going to judge others who do.” After all, what are we so afraid of?

This post was adapted and expanded from a 2013 post on Apartment Therapy.

References

Batchelor, David. Chromophobia. London: Reaktion Books, 2000.

Gage, John. Color and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Goethe’s Theory of Colours. Translated by Charles Lock Eastlake (London: Frank Cass & Co.; reprint London: Albemarle Street, 1840).

Grumbine, J. C. F. Psychology of Color (Cleveland: Order of the White Rose, 1921).

Loske, Alexandra. Color: A Visual History from Newton to Modern Color Matching Guides. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2019.

Munsell, Albert Henry “An Introduction to the Munsell Color System.” In Thomas Maitland Cleland, A Grammar of Color: Arrangements of Strathmore Papers in a Variety of Printed Color Combinations According to the Munsell Color System. Mittineague, MA: The Strathmore Paper Company, 1921.

Parsons, Frank Alvah. Principles of Advertising Arrangement (New York: The Prang Company, 1912).

Richards, Thomas. The Commodity Culture of Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851-1914 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990).

Smith, Mark M. How Race Is Made: Slavery, Segregation, and the Senses. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2008.

Taussig, Michael. What Color Is the Sacred? Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.