Aging

Time IS Money... But Not Like You Think

How thoughts about time can influence your savings habits.

Posted January 9, 2017

Every advisor has met them: The clients who will never outlive their wealth, but are so filled with anxiety that they cannot enjoy what they have. Then there are the ones who are plenty joyful…as they spend their way into the poorhouse. While they may not be easy clients to work with, these people are wonderful examples of why any meaningful definition of ‘financial wellness’ must include more than just the numbers on a balance sheet.

At Morningstar (where I work as a behavioral researcher), we have been combining psychographic research with traditional demographic approaches in order to learn more about the factors that drive financial wellness. Here, we will look at one of the findings from this work, which points to an important driver of wealth accumulation (the numerical dimension of financial wellness).

(Mental) Time is Money

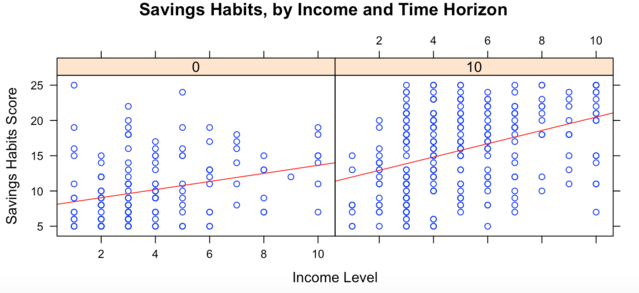

In a survey of several hundred Americans, we found that while income certainly affected people’s savings rates, other demographics such as age, education, gender, and region were less important. What was especially interesting was that a significant factor related to both savings balances and savings habits was unrelated to demographics. It had to do with time. Specifically, mental time.

People who think further into the future tended to save more frequently, and build larger savings balances in both the retirement and non-retirement savings categories. What was especially striking is that this effect was significant even when controlling for income, age, gender, and education.

In the graph above, the group on the left thinks in the short-term. The group on the right thinks several years ahead. Among those who think long-term, even those in the lowest income group (less than $10,000/year) had savings habits that rivaled short-term thinkers in the highest income group (more than $200K/yr). These habits included saving from every paycheck, saving up for large purchases, saving for long-term goals such as buying a home, and saving for retirement.

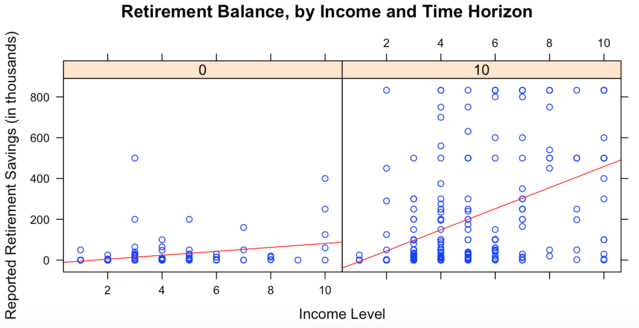

The contrast between long- and short-term thinkers is even more striking when we look at retirement savings balances.

In this graph, we see that when a person’s mental time horizon is short (the group on the left), they do not have nearly as much saved for retirement as those who think long-term, even when they earn many thousands more than long-term thinkers. Those who think in the long-term, as long as they are earning at least $25,000/year, are finding ways to save for retirement. Again, this effect was significant even when controlling for age, education, gender, and geographic region. Clearly, (mental) time IS money.

What’s a person to Do?

First, take stock of your mental time horizon. How far ahead do you tend to think and plan? A few weeks? Months? Years? Your day-to-day decisions will be deeply affected by your mental time horizon. Previous work I have done in this space showed that mental time horizon and clarity of one’s picture of the future may even reduce the effects of impulsiveness on financial behaviors.

If you find that you think fewer than five years ahead on average, you may be at risk for higher debt-to-income ratios, lower savings rates, and more impulsive spending. The good news is that there is hope.

Helping yourself to ‘see’ further into the future can affect the choices you make today. One fun way to do this is to age progress your face. When people feel closer to their future self they tend to be better savers.

Some people may shy away from seeing their face aged, however. In that case, visualization exercises can help you to think through the goals that you would like to reach in the future. Many financial advisors ask clients to write an essay that details what they would like their lives to be like when they reach financial independence, and bring it to their plan review meeting. This can help clients to refine their goals and pinpoint their priorities, which also helps in setting realistic numerical expectations for life after retirement. Where will you live? How will you spend your time? Who will you spend your time with? The important thing to remember with visualization is detail. In our research, we saw that clarity of a person’s mental picture had a large impact on behavior (almost as much as time horizon). The combination of thinking further ahead, and thinking with clarity and detail is a powerful mental trick to drive better savings behaviors.

Thinking ahead is a habit, and all habits take time to build. If you are accustomed to thinking short-term, trying to push your view out 30 years may be unrealistic. Do you only think about the next six months? Try to think about 1 year from now. Do you think a year or two ahead? Challenge yourself to make a three-year plan. This one mental factor can affect thousands of tiny daily decisions, and in the end, it may mean the difference between a timely, secure retirement and a delayed, precarious one.

More to Come

Next week, I will discuss one of the factors that drives the emotional side of financial wellness. A more detailed exploration of this work will be published in a forthcoming white paper from Morningstar.

—Dr. Sarah Newcomb is a behavioral economist for Morningstar, Inc.