Relationships

Surprise—There’s No Such Thing as Normal

We all have emotional dysfunctions.

Posted May 12, 2019 Reviewed by Davia Sills

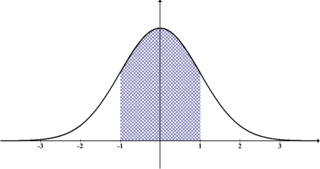

Believing in the Bell-Shaped Curve

We’ve been taught to believe a large percentage of the population is “normal.” In school, we learned about the bell-shaped curve and how most of us fell under the middle of the bell. We were taught that a few of us were at the extreme ends of the curve. But do we follow the supposed norm of emotionally and behaviorally well-adapted people? Do we rarely experience anxieties, depressions, addictions, problems with children, and marital dysfunction? Do most of us have balanced and happy relationships, devoid of significant strife and loaded with fulfillment?

No Normal Found in Clinical Practice

In over 40 years of clinical psychiatric practice, I have not found anyone who is normal. This is also the case for patients’ family members who do not seek treatment. This is true for friends, colleagues, and their family members. Every person has skews in his or her personality. These run the gamut from mild to severe in degree. Large groups of normal people are not found.

Homer B. Martin, MD, and I studied several thousands of people of all ages in long-term dynamic psychotherapy. We found that people raise their children in lopsided ways via what we call “emotional conditioning.” This is a form of classical conditioning that shapes people emotionally and teaches them how to conduct their relationships. This leads people to react to life’s run-ins in imperceptibly to considerably inappropriate ways. We all make errors in judgments, choices of mates and friendships, and in raising our children.

Don’t Confuse Normal With Not Seeking Treatment

We may think that normality does exist because of the sizable numbers of people who don’t seek psychological treatment. We may assume that these people are less emotionally or mentally perturbed or disturbed than those requesting treatment. Over decades we have found many patients’ family members to be more emotionally ill than the patients we saw. Two or more people can forge relationship problems, but only one of them may seek treatment. We found the seekers of psychotherapy treatment to be more distressed and inquisitive than were their ill family members.

Why Continue to Stigmatize?

If we all suffer from some level of emotional distress, dysfunction, or emotional or mental illness, where is the stigma? Should we continue to stigmatize one another? What does this do to us? We can only perpetuate emotional and mental stigma if we have a comparison population without such problems. We haven’t found these people. We’d be better off tackling the emotional difficulties we all share from the perspective of our shared and often problem-ridden humanity, not as them (the emotionally and mentally ill) versus us, the normal.

References

Holmes, A., & Patrick, L. (2018). "The Myth of Optimality in Clinical Neuroscience." Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22:3, 241-257.