OCD

Who's Trivializing OCD?

A Personal Perspective: Reclaiming the heart of a misunderstood diagnosis.

Posted April 3, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- There's been an alarming trend of media trivializing OCD.

- OCD's view as a bio-behavioral disorder has revolutionized its treatment, but also has hidden downsides.

- Examining the emotional experience and creativity underneath OCD offers a fuller perspective easily integrated into current treatments.

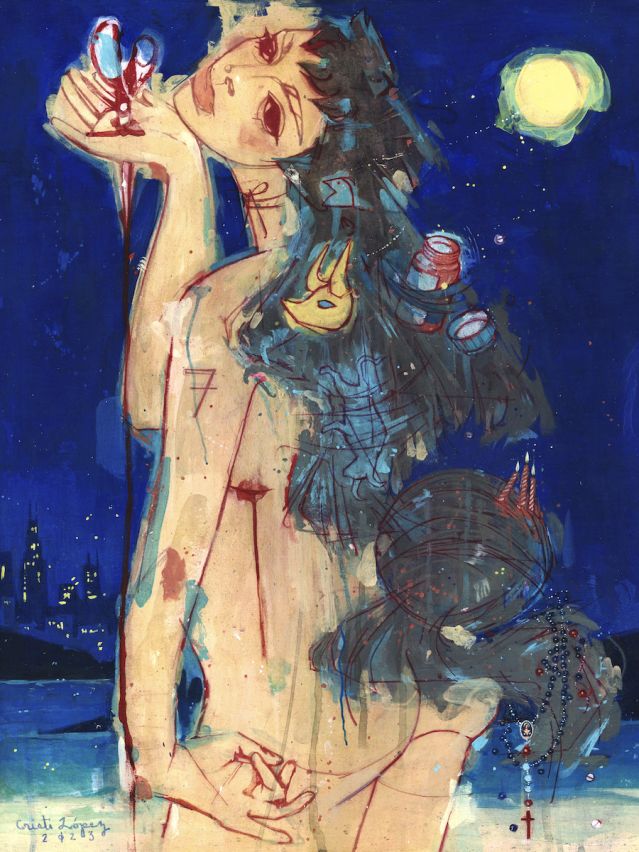

- This creativity is shown in notable OCD sufferers John Green, Greta Thunberg, Mara Wilson, and Cristi Lopez.

If you have obsessive-compulsive disorder, you may have felt trivialized by a lot this past year: a company using their designer cups to cheekily proclaim “I have OCD. Obsessive Cup Disorder”; a mental health advocate who doesn’t mind you saying you have “a little OCD”; or a major newspaper warning of the links between OCD, radicalization, and violence.

Although I cringe at these offerings, I can’t help but have some sympathy. My own Psychology Today piece entitled “OCD as a Superpower” gave me unexpected Christmas gifts in my inbox demanding that I be ashamed of myself and apologize immediately. As part of my mea culpa, I encouraged readers to go beyond the headline to learn new, empowering ideas most experts hardly recognize: OCD is much more than is currently made of it.

After OCD treatment was taken over from psychoanalysis as a hopelessly refractory disorder, it was branded a bio-behavioral issue to be primarily treated with medication and exposure-response prevention. ERP, as it’s affectionately called, helps people stay through their greatest fears so they become desensitized and free from the intricate tentacles of OCD.

A victim of its own success, OCD now takes on no other meaning. Cognitive-behavioral treatments view OCD as noise in the system meant to be tuned out. Think high-level chatter that most other regular mortals dispel as easily as swatting away a fly. In short, OCD became an enemy to be vanquished, a debilitating illness never to be trifled with.

But what if there’s more creativity and meaning inside OCD? What if those with OCD are directing attention to all the places that overtly minimize it, when the very treatments meant to save them are covertly doing the same thing?

In the case of OCD, the devil that you know isn’t better than the one you don’t. It may even be the angel you don’t know, the hidden gifts before OCD hits the scene, that just might save you.

My unconventional view, beginning to be supported by research, is that OCD results from a biological temperament characterized by a highly developed empathy and profound awareness of the fragility of life. When this sensibility isn’t well understood or harnessed, it degenerates into the crippling doubts, fears, and dread so emblematic of the Kafkaesque experience of OCD. However, when this unique temperament is nurtured and honored, there’s no stopping what heights it can take you.

Notable OCD sufferers like author John Green, climate-rights advocate Greta Thunberg, or actress Mara Wilson show how the underlying OCD sensitivity can give rise to beautiful existential prose, impassioned advocacy to save us from extinction, and acting capacities way beyond one’s years. Every day, individuals with OCD also showcase a high emotional intelligence and creative imagination woefully underappreciated by current OCD treatments.

I’ve had readers reach out to me from all over the world who felt like they were failing treatment when in reality, treatment had been failing them. A reader from France whom I’ll call Sophie told me:

“I’ve practiced CBT for a long time and it helped, but there’s an emotional part that’s the last piece of my puzzle that I need to finally be free. Your article gave me hope and touched the inner voice in me that always felt there was an emotional part I needed to deal with to overcome this.”

On a relational level, OCD attempts to establish clearer boundaries to compensate for the emotional blurriness that arises from such overdeveloped empathy. The need for constant reassurance highlights how much the OCD sufferer needs others to find their own boundaries, and yet OCD swoops in to create a world where it is in full control. A devil’s bargain, OCD takes on a life of its own, leaving the individual unable to capitalize on their immense potential.

A reader from Japan confessed:

“It brought me to tears [reading your work] as I've never been able to fully explain why I have this cleaning routine and why it feels like I'm wiping away to create personal space for me in my own home.”

OCD is not nearly as simplistic as either the overt or covert trivializers make it. It’s not just a biological glitch that makes one continually go down psychological rabbit holes nor is it an admirable or even useful experience when kicked into high gear. Until you learn about the angel that you don’t know—how OCD works on an emotional and relational level—you can’t ever truly get at its source and tap into its hidden upside.

Artist Cristi López represents this to perfection in her work. A first-generation American of Dominican, Spanish, and Cuban descent, López draws inspiration from symbolist painters Klimt, Kahlo, and Redon, Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele, and the bold primary color palette of Dominican folk art. All of these influences, along with repeating motifs can be seen in "Unravel," above, which depicts a wounded female nude against a backdrop of the Chicago Skyline. Like those who suffer and soar due to OCD’s hidden sensitivity, the main figure carries power, confidence, and emotional vulnerability; she evokes a sense of duality, intimacy, and frenetic calm.

The devil that we don’t know about OCD is that it does have meaning and creates chaos at the same time. Not unlike our regular dilemmas with political polarization, I believe that our approach to OCD would be better served by a greater openness to these multiple and complicated truths.

Ironically, much has been done to reify OCD as if it is the true dragon to slay. What if instead of talking about the dragon so much, we finally focus on freeing the princess?

References

Farmer, Sam (2019, December 12). 'How Greta Thunberg's autism helped make her the world's most important person for 2020' The Hill. https://thehill.com/changing-america/well-being/468091-opinion-activist…

Green, J. (2019). Turtles all the way down. Penguin Books.

Jansen, M., Overgaauw, S., & De Bruijn, E. R. (2020). Social Cognition and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review of subdomains of social functioning. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00118

Salazar Kämpf, M., Kanske, P., Kleiman, A., Haberkamp, A., Glombiewski, J., & Exner, C. (2021). Empathy, compassion, and theory of mind in obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 95(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12358

Szalavitz, Maia (2023, January 22). 'I Don't Mind If You Say You Have "a Little OCD"' The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/22/opinion/neurodiverse-ocd-mental-heal….

Wilson, M. (2016). Where am I now?: True stories of girlhood and accidental fame. Penguin Books.