Anxiety

Expanding the "Window of Tolerance"

Supporting children's ability to cope with anxiety.

Posted April 10, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Childhood can be filled with an array of worries, like separation anxiety, friendship problems, phobias, body image, and so many more. This article aims to provide parents with a new framework for supporting our children's anxiety issues by utilizing and understanding Siegel's (2010) "Window of Tolerance" and the impact of shame (Sanderson, 2015) in conjunction with coping strategies.

Although anxiety feels unpleasant, it is a natural alarm system designed to ignite our fight/flight/freeze stress response in order to survive. However, it can become overactive when harmless things trigger this stress response with false alarms, disrupting its normal functioning, creating unnecessary and overwhelming feelings. As parents, it is incredibly difficult to see our children in such distress; however, accommodating our child's fear to diminish their stress does not enable them to develop abilities to cope.

Likewise, ignoring their fear or telling them to "get over it" is also harmful, because it elicits shame and signifies that something is wrong with them for feeling this way and reinforces their inability to cope. With these responses, children tend to avoid their fears rather than learn to adapt and cope with uncomfortable feelings, which are believed to precipitate childhood anxiety.

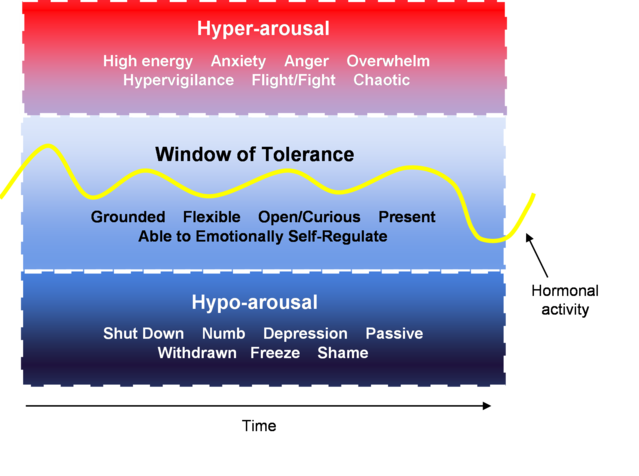

We all have windows of what we're able to tolerate; employing this concept in both parents and children can be a productive way to support children in broadening their ability to tolerate and cope with uncomfortable emotions like anxiety.

Our body is always releasing hormones to try to keep us as level as possible (homeostasis). When our hormones are more level (within our window of tolerance), we feel more able to handle situations appropriately. Within this window, we are adaptable, able to emotionally self-regulate, and deal with triggers more harmoniously. However, we all have a limit of what we're able to tolerate at any given time. When things become too much for us to tolerate, our hormones respond in one of two ways out of our window:

We either shut down or plummet into a hypo-aroused state (the parasympathetic nervous system is engaged, which is the freeze response to stress/danger). In this state, we may feel overwhelmed with shame, numb to emotions, withdraw, feel depressed, or dissociate in order to cope with the situation or trigger.

Or we shoot up into a hyper-aroused state (the sympathetic nervous system is ignited, which is the fight/flight response to stress or danger). In this state, we may feel fizzy with intense hormonal activity; we may feel angry, chaotic, hypervigilant, or experience anxiety and the accompanying symptoms.

How the window of tolerance relates to anxiety disorders: The sizes of our windows adjust in parallel to internal and external influences. When feeling stressed, sad, or lacking sleep or self-regulation skills, our window of what we're able to tolerate shrinks.

Having a small window means that we are less able to tolerate things and are more likely to be triggered into shooting out of our window. With repetition, routes of shooting out of our window entrench, become more easily accessible and increase the triggering of false alarms. Having not developed effective coping strategies, a child's overactive alarm system becomes progressively more severe into adulthood.

How shame restricts windows: Understandably, our care for our children's mental well-being may invoke frustrated feelings, which could transmit shaming messages to our children. These may range from subtle cues like eye-rolls to the more overt "Oh, for God's sake," and "Don't be so silly!" Sadly, these messages embed feelings of worthlessness and of "being defective" into their self-identity (Sanderson, 2015). As such, shame and negative self-talk is reinforced internally and will be their "go-to" response in situations that mirror the shamed experience. Feeling "defective," they develop maladaptive defenses in order to avoid shame, which further shrinks their ability to cope healthily with uncomfortable emotions.

Reduce shame and allow the window to expand:

- Remember, the most powerful antidotes to shame are empathy and compassion.

- Resist shaming verbal and non-verbal reactions (this can come from efforts to expand your own window of what you're able to tolerate).

- Allow them time to explore, listening actively and empathetically, being curious about their experiences rather than your own interpretations of their experience.

- Normalize their experience to help them feel less ashamed and more open to exploring.

- Balance shame with healthy pride, promoting self-compassion and self-acceptance.

- Support resilience-building in order to prevent the damaging impact of shame.

Building resilience to strengthen their ability to cope:

- Impart beliefs like: The world is pretty safe, people are pretty safe; I can cope with most things; I have some control over things that happen to me, and I can accept things that can't be changed.

- Mistakes are OK; they are lessons teaching us what could be different next time.

- Set realistic goals and maintain a hopeful outlook.

- Praise effort even if the desired result isn't met.

- Appreciation exercises—at the end of the day (or when applicable), talk about three things that you appreciate about your day.

Fear-reducing strategies to broaden windows:

- CBT techniques have been shown to be an effective treatment for improving anxiety symptoms as they teach healthy ways to cope by identifying maladaptive thoughts, behaviors, and feelings. Gradual exposure to fear triggers can help conquer fear, step-by-step, in safe environments.

- Narrative therapy techniques help to externalize the problem from the child. This allows the child to have autonomy and control in dealing with the problem in an imaginative way, removing the inadvertent shame which can be elicited through messages that the problem is entwined with the child's identity.

- Mindfulness is also a good treatment method, as we focus on the present, bringing us closer to the center of our window.

- Compassion-focused techniques remove shame, focusing on promoting self-compassion and self-acceptance to build resilience and widen their window.

Reflection on the window of tolerance in both ourselves as well as our children will enable us to be more mindful and recognize how we're feeling against our windows. This will help us, and our children, develop the self-regulation skills to get us back inside the window, to handle the situation more appropriately.

This post was guest-authored by Jade Emery, Assistant Psychologist, Lifespan Psychology, London, UK.

References

Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2010). From timid to tiger: A treatment manual for parenting the anxious child. West Sussex. John Wiley & Sons.

Sanderson, C. (2015). Counselling skills for working with shame. London. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. New York. Bantam.

White, M. (1988/9). The externalizing of the problem and the re-authoring of lives and relationships. In M. White (Ed.), Selected Papers . (pp. 5-28). Adelaide, Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: Norton.

https://www.attachment-and-trauma-treatment-centre-for-healing.com/blog…