Microaggression

They All Look Alike

Experience can improve accuracy in face recognition.

Posted August 9, 2017

I was standing near the front of an auditorium, waiting for the social psychologist Claude Steele to give a lecture on stereotype threat. Before Professor Steele appeared, an older White man summoned me toward him. He asked me to sign his book, Whistling Vivaldi, written by Professor Steele. I realized that the man thought I was Professor Steele. I explained that I was not. He insisted, “You look like him.”

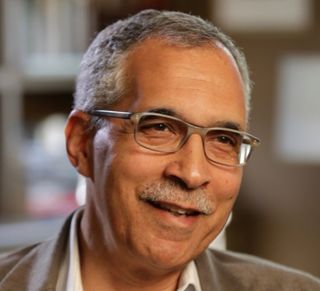

I think that because I was standing in front and had a relatively dark complexion, the man thought I was Professor Steele. You can look at our photos and decide for yourself if we look alike. Professor Steele’s parents were White and Black. Mine were White and Japanese.

Research demonstrates that we are better at telling people apart in our own group than in outgroups. Most people in the United States are White, which makes people of color the outgroup. So, most of the time, the people who are mistaken for someone else are people of color.

Is being mistaken for someone else harmful? Being seen as the same as everyone else in an ethnic group time and time again can feel like a microaggression. And microaggressions can harm physical and mental health.

The good news is that most people do

not have prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces. Inability to recognize outgroup faces comes from a lack of experience. Research also demonstrates that people are better at recognizing outgroup faces if they have more experience with outgroups. The more people outside your group you know, the better you are at telling them apart.

So, how do we get better at recognizing people from other groups?

- Exercise caution with other groups. Rather than starting with “sign my book”, the man could have asked, “Are you Claude Steele?”

- Apologize if you make a mistake. Instead of insisting that I looked like Professor Steele, he could have admitted his mistake. I certainly have when I have mistaken someone for someone else!

- Go outside your group. Seek out experiences where you are in the minority. Yes, you might be mistaken for someone else. But you will improve your own ability to tell others apart.

Past American Psychological Association President Richard Suinn has said, “Only penguins look alike.” Recognizing and appreciating the uniqueness of others can enrich your life. And theirs, too.

References

Wan, L., Crookes, K., Reynolds, K. J., Irons, J. L., & McKone, E. (2015). A cultural setting where the other-race effect on face recognition has no social–motivational component and derives entirely from lifetime perceptual experience. Cognition, 144, 91-115. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.07.011

Wong, G., Derthick, A. O., David, E. J. R., Saw, A., & Okazaki, S. (2014). The what, the why, and the how: A review of racial microaggressions research in psychology. Race and Social Problems, 6, 181-200. doi: 10.1007/s12552-013-9107-9