Psychology

The Psychology of Natural Versus Constructed Languages

Are all languages created equal?

Posted December 10, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Languages are psychological and socio-cultural creations.

- The difference between a natural versus a constructed language runs along a spectrum.

- Some constructed languages can evolve into natural-like languages.

Languages like English, French, Japanese, and Swahili are natural languages; they have evolved over time, within a community of speakers, with a shared culture, to facilitate communication. At an individual level, they are psycholinguistic bodies of knowledge, stored in people’s heads. At the societal level, they are transmitted from one generation to the next, evolving through well-documented psychosocial and sociolinguistic processes and pressures.

In contrast, constructed languages, sometimes abbreviated to conlang are invented, by one or more individuals, and their genesis can typically be pinpointed to a specific date, period, or event. A famous example of a constructed language is Esperanto—introduced in 1887 by L.L. Zamenhof, a Polish physician, whose aim was to create an international language that could be easily learned, to break down barriers between peoples. The language was named after Zamenhof’s pen-name, Doktoro Esperanto, Esperanto meaning one who hopes.

Why invent a language?

In one sense, all languages are invented, even English. But while the genesis of so-called natural languages are lost in the mists of time, we can often, more easily, pinpoint the birth of constructed languages.

The invention of a new language is motivated by a number of different factors, including ease of communication, such as Esperanto, or Blissymbolics, or to facilitate communication in specific contexts. They are also created to provide added realism in fictional worlds, for instance in movies and in literature.

A case in point is the alien language that features in the box-office-record-smashing movie. Avatar is set in the future on the lush planet Pandora, where the indigenous population of the planet is the Na’vi. Their language, was developed by a linguist, Professor Paul Frommer, from University of Southern California. Frommer created a partial language, with a vocabulary of around 1,000 words. To make the language sound distinctive and sufficiently alien, he deployed sounds that don’t exist in English, and thus would sound exotic to an English-speaking audience.

While human spoken languages draw from an inventory of possible human sounds, the number of distinct sounds, dubbed ‘phonemes’ by linguists, that a language uses varies quite widely. Naturally occurring spoken languages range from having as few as 11 distinct sounds—in the Amazonian language Pirahã—to as many as 144 sounds in some languages. For Na’vi, Frommer borrowed sounds from languages such as Amharic, spoken in Ethiopia, and Maori. While Na’vi might sound alien to English speakers, in fact, it’s far from being unearthly—it draws on the very sounds used in other human languages.

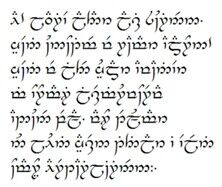

The case of Elvish

But some fictional languages are more elaborate; and some fictional languages even evolve over time, as their inventor works on them, or as the culture that they form evolves in the fictional world. A case in point is the Elvish language Quenya, developed by J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien even coined a word, glossopoeia, from the Greek, to refer to the activity of inventing languages, complete with its own mythology and culture.

The Elvish language and culture are developed in-depth in Legendarium—the mythopoetic body of writing that forms Tolkien’s background to The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien began working on Quenya perhaps as early as 1910 as a schoolboy—but it’s grammar continued to change, and develop over his lifetime, both as Tolkien continued to work on it, and due to the histories of the people that spoke the language. In this, Quenya mirrored the ways in which natural languages change over historical time. Yet while Quenya is more developed than Na’vi, it still lags far behind a natural language in terms of the semantic range that can be expressed; Quenya’s vocabulary remains impoverished, hence it just wouldn’t be possible to have a meaningful conversation in the language.

Can a natural language be artificially changed?

But while, on the face of it, natural and constructed languages appear to be very different, in practice the distinction between them can often become blurred—they often tend to form a spectrum, rather than there always being a hard and fast distinction. For instance, a natural language can be controlled so that it becomes more like a constructed language, coerced to conform to particular requirements for specific purposes.

A good example of this is so-called Plain English. The Plain English campaign began, in the UK, in 1979. Today, the British government adopts the principles of Plain English on all official uk.gov webpages, and in communications and publications by governmental agencies, and ministries.

Plain English represents a deliberate attempt to make English clearer for the public, by avoiding many idioms, jargon, and foreign words, while also keeping grammatical expression and constructions simple and direct. Even common Latin abbreviations, such as ‘e.g.’, ‘i.e.’, and ‘etc.’ are banned, replaced by English expressions, that, it is claimed, are easier to understand.

Can invented languages become naturally acquired?

In contrast, constructed languages can begin the process of becoming natural-language-like, especially as they acquire native speakers. Esperanto is a case in point. Although it was invented, there are multiple cases of children acquiring Esperanto as their mother tongue, and crossing the divide from being an invented to a natural language. For instance, a study published in 1996 found documentary evidence to support 350 individual cases of Esperanto having been acquired as a native language.

A more recent study, by Dr. Ben Bergen, examined the development of Esperanto as a natural language. Bergen examined eight native speakers of Esperanto and found that its grammar had diverged from standard (or invented) Esperanto in a number of ways; a particularly interesting change involved word order.

While invented Esperanto has a free word order, using grammatical case as a way of expressing the subject and object of a sentence, other languages express the same information using word order. For example, in contemporary English, word order is fairly stable, which is a canonical "subject-verb-object" word order: We use the order of the words to tell us who did what to whom. For instance, thumb a lift versus lift a thumb mean quite different things precisely because the position of the words lift and thumb are altered. But in English, it wasn’t always so. In Old English, sentence word order was much more flexible.

But just as contemporary English has lost much of its flexibility, developing a fixed word order (subject-verb-object) pattern, this is precisely what Bergen also found to have taken place with native Esperanto; the move from being an invented to a natural language seemed to also involve a shift away from free word order, to a more fixed syntax.

References

Corsetti, R. 1996. A mother tongue spoken mainly by fathers. Language Problems and Language Planning 87/4: 63-4.

Bergen, B. 2001. Nativization processes in L1 Esperanto. Journal of Child Language, 28/3: 575-595.