Cognition

Language Has a Past, Family Trees, and Even Character

How well-heeled is your language?

Posted July 5, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Just like people, a language has a past, a family—languages also have family trees—and even a particular social status.

- English is a Germanic language that began to take shape following the arrival of invaders from northern Europe.

- Language changes over time, becoming unrecognisable in just a few hundred years.

Language, like people, is a living, breathing organism, that changes and evolves. And just like people, a language has a past, a family—languages also have family trees—and even a particular social status, due to how well-heeled a particular language variety is perceived to be.

English: The invading tongue

Let’s take English. English is a Germanic language that began to take shape following the arrival of Germanic invaders from parts of what is, today, The Netherlands, northern Germany, and Denmark. The various tribes, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, that morphed into the English, spoke dialects of Old Frisian. In just over a hundred years they had established various kingdoms in what is today England, exploiting the vacuum created by the departure of the Roman legions from Britain around 410AD. Indeed, the legend of King Arthur is based on a historical figure, who united the Romanised Celtic tribes, initially with success, against the threat of these new invaders.

But in a cruel twist, the Celts were eventually relegated to the margins of the British Isles: the English words Wales and Welsh are derived from the Anglo-Saxon term for ‘foreign land’ and ‘foreigner’—the Anglo-Saxon root was wahla; in modern German the expression also survives as welsch, meaning ‘strange’. The irony is that the Welsh, among the original Celtic Britons, were labelled ‘foreigners’ in their own land, by the invading English. And the irony is not restricted to the British Isles; in Switerzland, the French-speaking canton is dubbed Welschschweiz in Swiss German: literally, ‘strange or foreign Switzerland’.

From a psychological perspective, this is a form of linguistic "gas-lighting": original peoples are identified as foreign or, worse, other. And in this way, land grabs and conquest are normalised through language.

The past recorded in names of place

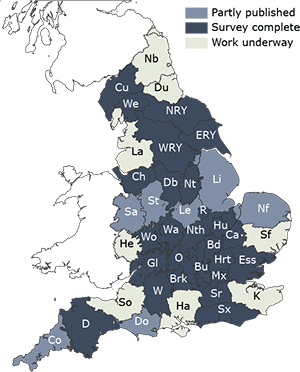

The early settlement patterns of these Germanic invaders have left an indelible mark on English place names, as made clear by the Survey of English Place Names. For instance, Sussex, Essex, and East Anglia describe present-day regions of England that are abbreviations of once noble Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: South Saxon (Sussex), East Saxon (Sussex), and the land of the Eastern Angles (East Anglia).

Moreover, in the novels of the great English 19th-century writer, Thomas Hardy, who situated his fiction in Wessex, even this fictional world relates to another Anglo-Saxon Kingdom; Wessex was ruled by the fabled Anglo-Saxon king, Alfred the Great, 871 to 899, who united the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms against their common enemy: The Vikings.

By the time of his death, Alfred had become the preeminent king of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy: the seven Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms of England that emerged during late antiquity: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. These kingdoms were eventually united into the Kingdom of England, in 927, by Athelstan, the capital of which was Winchester, in Wessex—until the capital was relocated to Westminster, near modern-day London, following the Norman conquest of England in 1066. And England was a sovereign nation until 1707, when it was unified with Scotland, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Yesterday is a foreign country

But Old English—the English spoken in England until around the time of William the Conqueror in 1066—is today a foreign tongue, barely recognisable, to contemporary speakers, as English. Consider the following extract, written by Ælfric of Eynsham (955-1010), an Abbot and prolific writer in Old English. The following is from his colloquy, a conversation manual from the tenth century intended to help speakers of Old English learn Latin:

We cildra biddaþ þe, eala lareow, þæt þu tæce us sprecan [ . . . ] forþam ungelærede we syndon & gewæmmodlice we sprecaþ. Hwæt wille ge sprecan? Hwæt rece we hwæt we sprecan, buton hit riht spræc sy & behefe, næs idel oþþe fracod. Wille beswungen on leornunge? Leofre ys us beon geswungen for lare þænne hit ne cunnan. Ac we witun þe bilewitne wesan & nellan onbelæden swincgla us, buton þu bi togenydd fram us.

Here’s the modern English translation:

We children ask you, oh teacher, to teach us to speak Latin correctly, for we are unlearned and we speak corruptly. What do you wish to talk about? What do we care what we talk about, as long as the speech is correct and useful, not idle or base. Are you willing to be beaten while learning? We would rather be beaten for the sake of learning than remain ignorant. But we know you to be kind, and you do not wish to inflict a beating on us, unless we force you to it.

This reveals, lest there be any doubt, that Old English really was a foreign language. And over time, English has continued to evolve, morphing into the Middle English of Chaucer—here are the opening lines from the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales, which is somewhat more recognisable as ‘English’ to contemporary speakers:

Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

Tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the ram his halve cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(so priketh hem nature in hir corages);

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.

Here is the modern English:

When April with his showers sweet with fruit

The drought of March has pierced unto the root

And bathed each vein with liquor that has power

To generate therein and sire the flower;

When Zephyr also has, with his sweet breath,

Quickened again, in every holt and heath,

The tender shoots and buds, and the young sun

Into the Ram one half his course has run,

And many little birds make melody

That sleep through all the night with open eye

(So Nature pricks them on to ramp and rage)-

Then do folk long to go on pilgrimage.

And while Chaucer remains a challenge, still foreign-looking and sounding, for today’s Millennials, it slowly gave way to the early modern English of Shakespeare: for some, still inscrutable.