Neuroscience

The Cognitive Science of Top Gun: Maverick

Psychologists can learn from story grammar in blockbuster movies.

Posted June 23, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Story grammar is a universal structure for narratives.

- The early 20th-century story grammar can be applied to blockbuster movies as well.

- Story grammar suggests that humans use story templates for comprehending and generating stories.

- These templates are of interest to clinical psychologists and cognitive scientists alike.

One of my academic heroes is Vladimir Propp. Propp was a literary scholar and folklore researcher who analyzed the narrative structure of Russian fairy tales. In his analysis, he concluded that a sizeable number of Russian fairy tales had some remarkably similar structures. A universal grammar expressed in 31 functions. Propp reported his findings in Russian in 1928. His work was first translated into English three decades later.

Why is Propp my academic hero? Propp was one of the first interdisciplinary scholars who strongly argued for using the methods of sciences for topics reserved for the humanities. Put differently, he argued for looking at the alpha sciences from a beta perspective. What you get is the gamma sciences (what we know as the social sciences).

But Propp was also the first who proposed story grammar. Well before linguists argued for universal grammar in sentences, Propp argued for universal grammar in stories. It turns out that the story grammar he found for Russian fairy tales can be easily applied to other stories.

Another academic hero of mine is David Rumelhart, a cognitive scientist known for his work on neural networks; Rumelhart followed up on Propp’s work in 1975. At a time when linguists focused on sentence grammar, Rumelhart revived Propp’s morphology of the folktale and proposed that many stories involve some kind of problem-solving motif whereby something happens to the main character, which sets up a goal that must be satisfied. The story then centers around the main character reaching that goal and the results from that behavior.

One may ask why we have all heard about sentence grammar but not so much about story grammar. The answer: There are some practical difficulties with those story grammar. First of all, for sentences the unit of analysis is easy. Sentences are made up of words. One could tag each word as a determiner, adjective, noun, or verb. Once we have established some agreement on these tags, we can look at the configuration of these tags in a sentence. We may find that adjectives go together with nouns, and these combinations are preceded by a determiner, and together with a verb, they become a sentence. The brown fox jumped, the green ogre laughed, and the young lady smiled.

For story grammar, things are a bit trickier. The unit of analysis may be an action, such as a fight with a dragon. But how is such an action really defined? Is it a sentence? A paragraph? Or a series of events? And do these actions all have similar lengths? And unlike sentences, much can be left implicit in stories. If the hero was directed to retrieve a ring, fight the dragon, and get married, I left out so much information that the story has just become utterly boring (and extremely short) but you would still get the gist and can reconstruct the story.

Back to Vladimir Propp who identified 31 functions in Russian fairy tales. If these functions indeed extend well beyond the fairy tales to other stories, this ought to be of interest to psychologists and cognitive scientists. It would mean that the mind somehow applies templates for story comprehension, templates that may say something about why we like storytelling, why we are so good at storytelling, and how computers may be able to analyze or even generate stories.

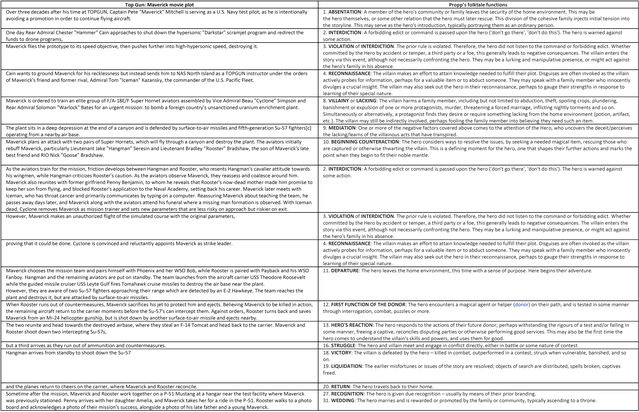

Let me do justice to the title of this post, meanwhile illustrating why Propp is my academic hero. After all, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Let’s take one of the most popular stories of today, the blockbuster that only two months after its release is already the 64th best-selling movie of all time: Top Gun: Maverick. Let's compare the movie plot, taken from its Wikipedia page, with the 31 functions Propp defined, taken from his Wikipedia page See full comparison table here.

Next time you watch a movie, you may look back on what was proposed in 1928. And what cognitive science may have to offer when all you do is simply enjoy an entertaining story.

References

Louwerse, M. (2021). Keeping Those Words in Mind: How language creates meaning. Rowman & Littlefield.

Propp, V. I. (1928/1968). Morphology of the Folktale (English translation). University of Texas Press.

Rumelhart, D. E. (1975). Notes on a schema for stories. In Representation and understanding (pp. 211-236). Morgan Kaufmann.