Coronavirus Disease 2019

How Does an Airborne Virus Get Into the Brain?

This is one of the pandemic’s mysteries.

Posted April 23, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- For some survivors, the after-effects of Covid continue for too long, and not just in the lungs, but in the brain.

- The virus can become neuroinvasive, literally invading the brain.

- Patients who had mild cases suffer from significant cognitive challenges long after physical recovery.

When the virus that came to be known as SARS-CoV-2 hit the news in early 2020, it got the immediate attention of the world’s top infectious disease specialists and pulmonologists – the former due to its spread and the latter because of the devastation the disease wrought in the lungs of the most severely ill patients. The “ground-glass opacity” seen on chest X-rays was an ominous sign, and so very many people struggled to breathe through difficult weeks and even months. For some survivors, though, the after-effects continue too long – not just in the lungs, but in the brain. For brain specialists, this poses challenging questions about how the virus gets into the brain as well as what to do once it’s there.

The Blood-Brain Barrier Is No Match for Covid

In healthy individuals, the brain has a remarkable defense mechanism – the blood-brain barrier – that protects itself from infections, drugs, and other toxins. It’s an evolutionary development that keeps our most important organ safe from substances that might harm it. It’s also the barrier we face when we investigate how to get drugs into the brain to fight tumors, Alzheimer’s, and movement disorders such as Parkinson’s.

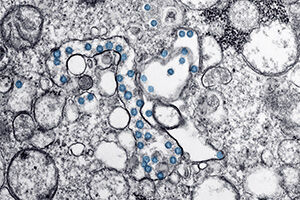

Unfortunately, in some cases, the blood-brain barrier is no match for Covid-19, with evidence suggesting that the virus can become neuroinvasive, literally invading the brain. How it does that, exactly, is not entirely clear. The viral entry point in the nose, with the connection of olfactory cells to the olfactory bulb in the brain, may be one clue. In some patients, we have seen damage to the endothelium, the lining of the blood vessels. Damaged vessels may allow blood to leak into the brain, taking the virus and its characteristic spike proteins with it. Unaccustomed to and unprepared for these proteins and viral particles inside it, the brain reacts by ordering up the release of cytokines to fight off the invaders.

You’ve probably heard about the “cytokine storm,” the uncontrolled immune response that the body sometimes mounts in response to severe or unusual infection. The presence of the virus, the overreaction of the immune system, and the uncontrolled brain inflammation are all factors in the scrambling of the brain’s normal function, creating the cognitive issues that characterize what we call “long-haul Covid.” Even patients who never experience the cytokine storm or brain inflammation can find themselves in that long-lasting cognitive fog.

How Long Is Long Covid?

Of course, with barely a year of experience with this particular virus, we don’t know how long is long. Researchers who have studied the long-term effects of other viral infections, including HIV and SARS/MERS, are bringing that experience to their investigations into Covid. We’ve already seen some unexpected findings: For example, although it’s clear that those who had Covid-related strokes or seizures are at high risk for cognitive symptoms later, the reverse is not true. One of the most interesting things we’re seeing is that patients who had relatively mild cases of the viral disease suffer from significant cognitive challenges long after they’ve recovered physically — some patients even report issues more than six months after Covid infection.

The most common cognitive complaints our neuropsychologists hear are difficulty paying attention for long periods, what patients refer to as “brain fog,” an inability to think clearly, an inability to find the right words in conversation, and an inability to process information as quickly as they did before.

These are similar to what neuropsychologists see in other conditions that affect the brain this way, including accidental injury, multiple sclerosis, or chemotherapy. The cognitive remediation that our neuropsychologists offer to these patients can also help Covid patients experiencing the same symptoms.

Neuropsychologists approach the brain more in terms of functional domains more than physical structures – in addition to those familiar “lobes of the brain” diagrams we’ve all seen there are domains for working memory, attention, visual-spatial skills, executive function, processing speed, and language. When one of those domains is weakened, neuropsychologists can train patients to call on skills they continue to have to compensate for their areas of difficulty, and they can teach strategies for strengthening areas that have been weakened.

In many ways, we are in uncharted waters with Covid-19, but we do have many years of learning about brain function and how to regain it after injury. There is still stigma attached to it, unfortunately, nobody blames a stroke patient for taking too long to regain use of an arm or leg, but there can be judgment about a Covid-19 patient who can’t seem to return to their pre-Covid functioning. Compounding the problem is the emotional fallout of the illness; patients experience anxiety, depression, even PTSD. One of my missions is to help people see the brain as the complex organ that it is – it’s an organ that manifests its injuries in physical, emotional, and cognitive ways, all of them worthy of compassion and care.

Two of my recent podcast episodes touched on this topic: One covers the pathology and neuropsychology of the virus’s effects on the brain and the other, “How Gabby Giffords Found Her Voice,” covers how the former U.S. Representative relearned speech by using music after a near-fatal assassination attempt in 2011.