Environment

How We Frame Emotions Through Facial Expressions

In art and in real life, our faces tell stories that we reveal to others.

Posted April 20, 2015

Facial expressions offer potent displays of emotions and to a large extent are universally understood. Yet the social context or framing around an expression is important and can color how we interpret emotions. Thus, a smile may be viewed differently depending on the situation, what happened just prior, or the disposition of the person transmitting or receiving the expression. In some cases, the same stimulus can elicit very different facial expressions from observers. My favorite painting that exemplifies this point is Bartolomé Esteban Murillo's Two Women at a Window (c. 1655/1660). Here two women are viewing the same stimulus, though their expressions are very different—one of youthful longing and the other of embarrassment. We can guess (very easily) what the two women are observing.

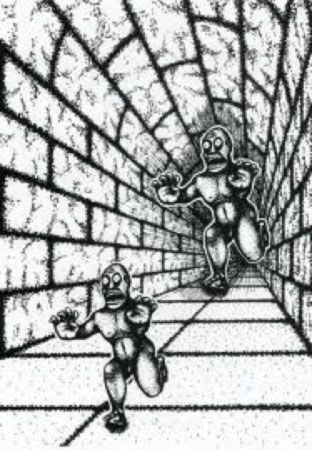

In the case of Murillo's painting, the same stimulus elicits different facial expressions. There are other cases in which the same facial expression is interpreted differently. The clever drawing by the renown psychologist Roger Shepard is often used in introductory psychology textbooks as an example of a perceptual size illusion. The two monsters are identical in every way, except for their placement in the tunnel, which makes the monster in the back look much larger than the one the foreground. This perceptual illusion, which is driven by linear perspective, is so strong that the only way to be fully convinced is to get out a ruler and measure the two monsters. Shepard also noted that there is an emotional illusion as well, which was investigated by my former graduate student, Diane Marian (Marian & Shimamura, 2012). Within the context of the drawing, the monster in the foreground is described as scared, whereas the one in the background is described angry, even though both expressions are physically identical. We, as observers, interpret the emotions expressed and based on this situation, the background monster is viewed as an angry chaser, whereas the foreground monster is the fearful victim.

Among aficionados of filmmaking, Lev Kuleshov, the Soviet silent film director, is known for his use of editing to evoke different emotions. He took shots of an actor posing with a neutral expression and placed them after various scenes, such as one of a bowl of soup, a child's coffin, and a seductively dressed woman. Depending on the preceding shot, the actor's "neutral" expression appeared to change—from one of hunger to sadness and then to lust, even though the expression itself was the same .

In a set of psychological experiments, Diane Marian and I played on a kind of Kuleshov effect by presenting short film clips of facial expressions that changed over a few seconds (Marian & Shimamura, 2013). Consider the following scenario: you are at a party and you look up from a conversation and see an unfamiliar face turn and smile at you. Your emotions would be buoyed. Now roll that film in reverse and consider how you'd feel if you looked up and saw someone smiling at you, but then the expression faded to a blank stare. In our experiment, we showed a variety of short film clips in which expressions moved from a neutral expression to happy, from happy to neutral, from neutral to angry, and from angry to neutral. What was rather surprising was that the same neutral expression looked different depending on whether it was preceded by the person looking happy or angry. If a smiling face moved to a neutral expression, then the person actually looked a little grumpy. If an angry face turned to neutral, that person suddenly looked a little happy.

These effects have the appearance of a perceptual illusion as the very same "blank" expression actually looks different (grumpy or mildly happy) depending on whether it started out as a happy or angry expression. In fact, in our everyday experiences, we never interpret facial expressions as static, momentary images. Facial expressions move within a rich contextual environment as they track and signal social interchanges. Of course, movies play on a character's facial expressions as the plot thickens. Jack Nicholson's evolution into madness in The Shining comes immediately to mind. These influences reinforce the idea that much of our emotional involvement—in everyday experiences and at the movies—is an unfolding and dynamic experience that occurs as much in the brain as outside it.