Cognition

Do Your Eyes Reveal What You’re Thinking?

Research shows how changes in your pupils reveal the contents of your thoughts.

Posted January 31, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

In today's technological world, many aspects of privacy we once took for granted are practically nonexistent. Our smartphones know our precise location throughout the day; our web browsers can predict what we are about to search; and advertisers have access to more information about us than we may have about ourselves. Still, amidst these technological intrusions, we like to think that at least our internal thoughts remain private.

As it turns out, even the contents of our imagination have a way of revealing themselves through the behavior of our eyes — specifically, that of our pupils.

The Pupillary Response

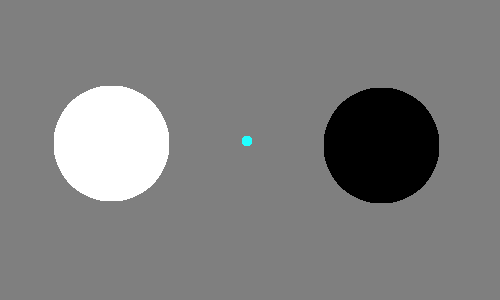

It has long been known that our pupils respond to changes in light: They constrict in response to bright light and dilate in response to darkness. More recently, research has shown that our pupils also change size in response to internal factors, such as our emotional state, cognitive effort, and how our spatial attention is allocated. In research by Paola Binda, Maria Pereverzeva, and Scott O. Murray (2013), participants were presented with a gray screen with a bright disk on one side, a dark disk on the other, and a fixation dot in the center, like in the image below:

Participants were instructed to fixate their gaze directly on the center dot, but covertly pay attention to either the bright disk or dark disk, depending on the particular instruction given before each trial. In control trials, participants were instructed to look directly at either the bright or dark disk. Binda and colleagues found that simply attending to the bright or dark disk — without actually looking at it — was enough to modulate participants' pupil sizes in a similar way as when they looked at a disk: constricting when attending to the bright disk and dilating when attending to the dark disk. The magnitude of the pupil size change induced by attention was about 37% as large as when participants looked directly at the disks.

Imagination-induced pupil changes

Subsequent research by Bruno Laeng and Unni Sulutvedt (2014) took this one step further, asking whether merely imagining something bright or dark is enough to produce a pupillary response. In each trial, participants first observed a gray screen on which a triangle shape appeared for 5 seconds, at one of several shades of gray ranging from very dark to very light. After that, the screen turned black for 8 seconds to allow the pupils to return to baseline, and then a gray screen appeared for 5 more seconds during which participants were asked to imagine the triangle they had just observed, in the same shade of gray as it had appeared.

Participants’ pupillary responses to the real triangles followed the expected pattern: Pupils became more and more constricted the brighter the triangles were. Intriguingly, pupillary responses to the imagined triangles followed nearly the exact same pattern, constricting more and more the brighter the imagined triangle was. Similar to Binda and colleagues’ findings, the pupillary response to imagined stimuli was smaller in magnitude compared to the real stimuli.

In a series of follow-up studies, Laeng and Sulutvedt tested multiple alternative explanations for their findings, including the possibility that participants willed their pupils to contract or dilate in anticipation of the experimenters' hypothesis. In fact, in their fifth experiment, participants showed no ability to purposely dilate or constrict their pupils, even when instructed to do so.

Indirect control

These findings show that although we may not be able to directly dilate or constrict our pupils, we can achieve a pupillary response indirectly, by using our imagination. According to Laeng and Sulutvedt, if we take a few seconds to imagine a sunny sky, our pupils will get about 0.55 mm smaller. If we instead imagine a totally dark room, our pupils will get about 0.61 mm larger. These changes are substantial enough that they may even be noticed by other people, or by machines.

Thus, our apparent (indirect) ability to modulate our pupil size using imagination has a more ominous implication for our privacy: Whether we want to or not, some aspects of our internal mental imagery reveal themselves through the behavior of our pupils.

References

Binda, P., Pereverzeva, M., & Murray, S. O. (2013). Attention to bright surfaces enhances the pupillary light reflex. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(5), 2199-2204.

Laeng, B., & Sulutvedt, U. (2014). The eye pupil adjusts to imaginary light. Psychological science, 25(1), 188-197.