Fear

"You're a Radical Behaviorist Disguised as a Neuroscientist"

A misunderstand about me based on a misunderstanding about brain and behavior

Posted October 23, 2019 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

This is the second of a series of posts related to my new book, The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains. The first post (How Deep Do We Go?) explained why I wrote a book about the history of life, and it also discussed the very ancient (billions of years) roots of fundamental aspects of human behavior.

The present post dives into questions about behavioral control and the fact that different kinds of behavior depend on different brain circuits. It was prompted by Facebook comment titled: LeDoux or Skinner? The mode of inquiry is different but the underlying assumptions are nearly identical. This reminded me of a related comment by a cognitive scientist who, after listening to a lecture I gave to her department, said, "You’re a radical behaviorist disguised as a neuroscientist."

In both cases, there was a kernel of truth to the description. For example, I have long argued that the neural circuits underlying the control of innate and conditioned behavioral and other bodily responses to danger operate nonconsciously. However, that does not make me a radical behaviorist. Just because I say that nonconscious explanations are adequate in accounting for some behaviors does not mean that I think they are sufficient for all behaviors.

In The Deep History of Ourselves, I make a point of emphasizing the wide range of behaviors that can be explained without the need to call upon conscious mental states; included in this category are all the standard behaviors studied by behaviorists: reflexes, fixed reaction patterns, Pavlovian conditioned responses, instrumental stimulus-response habits, and even instrumental goal-directed responses. Consequently, a behaviorist account based on reinforcement principles is just fine for understanding how Pavlovian associative processes connect meaningless stimuli to hard-wired output response modes via plasticity in the amygdala. It is also sufficient to account for how instrumental (operant) conditioning, via amygdala interactions with the nucleus accumbens, allows the use of cues predictive of harm to select instrumental behaviors that have been learned via their reinforcing consequences in the past to help avoid being harmed in the present.

But when we are in danger, we don’t just behave in protective ways. We also consciously feel fear. And this is where I part with traditional behaviorists views.

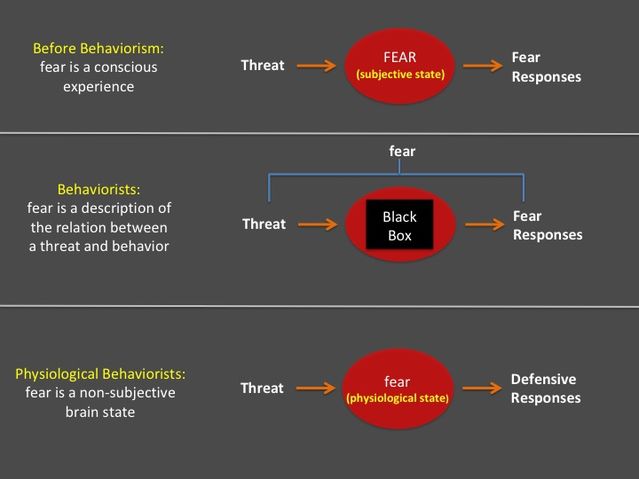

As is well known, the behaviorists banned the use of subjective experience as a way of explaining behavior. They had good reasons for doing this. In late 19th and early 20th century, anthropomorphism was rampant in the study of animal behavior, and subjective states were freely called upon to explain human behavior. It was the wild west of subjectivity, and it was simply assumed that subjective fear explains why animals and people run from danger (Figure 1 top), despite William James' early warning that maybe this was not correct.

Curiously, although behaviorists banned subjective states as explanations, they retained the use of subjective-state terms to describe behavior (Figure 1 middle). For example, for them, fear was a characterization of the relation between a dangerous stimulus (a threat) and the behavioral responses that the organism expresses to cope with the impending harm. Nothing inside the "black box" (the mind) needed to be considered.

Early behaviorists disliked inner brain states almost as much as mental states. This changed in the 1950s, when some psychologists began studying the brain mechanisms (brain areas and physiological states) that control behavior. But in other respects these physiological psychologists remained true to their behaviorist upbringing and resisted the temptation to attribute subjective experiences to these physiological states (Figure 1 bottom).

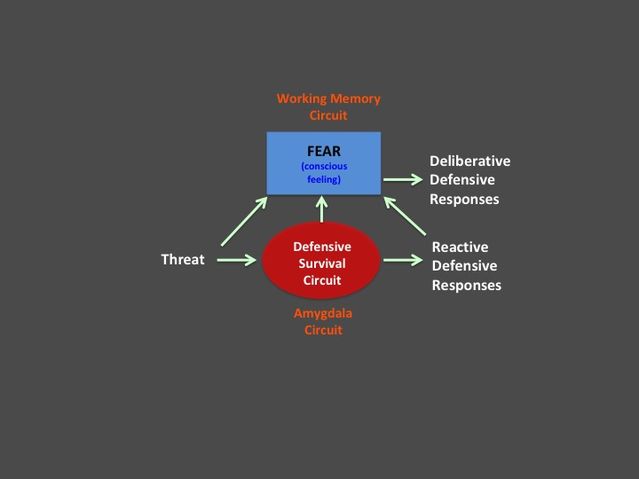

For example, activation of the physiological state of fear by danger was said to elicit defensive behavior. Once it was discovered that damage to the amygdala prevented danger from eliciting defensive responses, the amygdala came to be thought of as the home of this physiological fear state (Figure 2 top). Behaviorism was still very influential and it was simply assumed that everyone knew that the state was not a subjective one. However, this was seldom explicitly mentioned.

As the influence of behaviorism weakened over the subsequent decades, the taboo on subjective states began to lift, and psychologists started talking more freely about fear and other emotions as ways to account for behavior. This revival of subjective experience brought back some of the old problems the behaviorists had tried to avoid--anthropomorphism in animal research and unconstrained attribution of conscious control in explaining human behavior. But this time, there were no ground rules and rigorous criteria for when subjective states should and should not be used were lacking. Scientists simply took stands based on commonsense intuitions and personal beliefs, and no one seemed to mind.

For example, researchers such as Jaak Panksepp began claiming that animals have human-like feelings because they behave the way we do--why would a rat freeze in the presence of danger if not out of fear? He was a proselytizer with broad public appeal, and his views helped establish the notion that the amygdala is responsible for conscious feelings of fear (Figure 2 middle).

But also enabling this view was the loose talk by physiological-state researchers. Given their roots, either personally or through their mentors, in behaviorist principles, the general assumption was that the physiological state was not responsible for conscious fear. This was so ingrained it hardly needed saying. But because the behaviorists had retained fear and other subjective-state terms, the researchers often used expressions such as rats were frozen in fear that could easily be understood, by those not "in the know," as implying that conscious fear was instantiated in the physiological state.

My position differed from and overlapped with both the physiological- and subjective-state views. For example, in the early 1990s, I borrowed a distinction from memory research to help me be clearer about what I meant when I talked about fear and the amygdala. I referred to the amygdala as an implicit (nonconscious) fear processor (consistent with the central-state folks). But contrary to the physiological-state folks, I also championed the importance of conscious emotional experience (consistent with Panksepp). But contrary to Panksepp, I argued that the amygdala is not the source of conscious fear. Explicit (conscious) fear, I said resulted from the cognitive interpretation of one’s situation by prefrontal working memory circuits (see below).

The implicit vs. explicit fear idea never really took hold and, in some ways, actually strengthened the amygdala subjective-fear-circuit idea since it was too easy ignore the adjectives ("implicit" and "explicit"). The amygdala simply became a "fear circuit." And a fear circuit, of course, makes "fear."

To be honest, I was not always clear myself, and am certainly not free of blame for the the semantic morass about fear. To make amends, in 2012 I began to challenge my colleagues to be clear, and I offered a way forward. I proposed that we simply describe what the amygdala does in dangerous situations in terms of what we actually know that it does, rather than what we intuit it does. It detects threats and controls responses that help keep you alive. In short, the amygdala is not a fear circuit but instead a defensive survival circuit (Figure 2 bottom).

But what about conscious fear? How does it fit into this scheme? I have been thinking about how the brain makes conscious experiences of emotions, like fear, for a long time. I did my Ph.D. on consciousness in split-brain patients in the mid-1970s and got interested in conscious emotion then. I then turned to studies of rats to understand some of the basic mechanisms of how the nonconscious factors that accompany conscious fear operate biologically.

But my basic idea since the 1970s has been that emotions are cognitively assembled conscious experiences, an idea I borrowed in part from my mentor Mike Gazzaniga and from social psychologists like Stanley Schachter. The ideas were refined by also borrowing from Tim Shallice, Allen Baddeley, and later cognitive scientists. A highly simplified cartoon version of my current view of how the cognitively assembled state of fear assembled in the prefrontal cortex interacts with defensive survival circuits is shown in Figure 3. Many more details can be found in The Deep History of Ourselves.

I thus believe consciousness is a key part of human nature. And that is why, although I support behaviorist principles in accounting for many aspects of behavior, I am not a radical behaviorist.

.

References

Baddeley A. (1981) The concept of working memory: a view of its current state and probable future development. Cognition. 10:17-23.

Gazzaniga, M. S. The Bisected Brain. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1970.

James William (1884) What is an emotion? Mind 9:188

LeDoux, Jospeh E. (2012) Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron 73, 653-676.

LeDoux Joseph E. (2017) Semantics, Surplus Meaning, and the Science of Fear. Trends in Cognitive Science. 21: 303-306.

LeDoux Joseph E. (2019) The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains. New York, NY: Viking.

LeDoux, Joseph E. and Brown Richard (2017) A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, E2016-E2025.

LeDoux Joseph E., Brown Richard, Pine Daniel, Hofmann Stefan (2018) Cerebrum. 2018 Jan 1;2018.

Panksepp J. (1998) Affective Neuroscience. New York, NY (Oxford University Press).

Schachter S, Singer JE (1962) Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol Rev 69(5):379–399.

Shallice T. (1972) Dual functions of consciousness. Psychol Rev. 79:383-93.