Eating Disorders

Holistic Parenting Approaches for Eating Disorders

How parents can support their child's treatment and recovery

Posted March 11, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

The Struggle Is Real

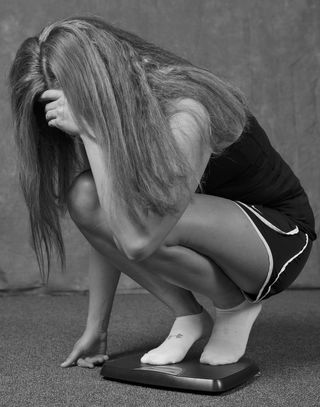

Given the media we consume, our culture’s lingering, unavoidable preoccupation with “weight loss,” and this chronic drive for perfection and order amidst our broken, chaotic world, it’s no wonder that more and more people are turning to food as a method of control and distraction. When pushed too far, these behaviors and mindsets can shift from something innocent to a serious and potentially life-threatening condition. Pair this with America’s epidemic with processed foods and massive confusion over what to actually eat, and we have ourselves a bit of a mess. In this post, I address holistic parenting techniques and approaches for eating disorders among children and adolescents

Integrative Approaches

Eating disorders are on the rise, and they present an enormous challenge to our society. For they impact not just the suffering individual, but parents, families, and society at large. Characterized by abnormal or disturbed eating habits, eating disorders wreak havoc on one’s physical and emotional health, and at least 30 million people of all ages and genders are believed to suffer from an eating disorder in the United States (ANAD, 2019).

Due to the complexities of these conditions, eating disorders can be very difficult to treat. As a result, unfortunately, they have the highest mortality rate of any mental health-related condition (Mehler & Brown, 2015). Parents especially can feel lost and powerless when their child is caught in the grip of these behaviors, and unsure of which direction to take for their child’s treatment. Parents, if you can resonate with any of this, these holistic parenting approaches for eating disorders were written for you.

Note: While the DSM V refers to specific eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia, I’ll primarily refer to these conditions instead as “eating disordered behaviors,” unless the research itself uses this specific terminology. As a reminder, none of the information in this article should take the place of advice or recommendations from your current provider.

Prioritize Food as Medicine

Individuals with distorted eating patterns often hold rigid mindsets around food. Weight loss, dieting, and counting calories become primary concerns that can easily take over. Skipping meals, taking very small portions, or hiding food also serve as common eating disordered behaviors. Many strive to reach a low weight, but can’t ever seem to get “low enough.” As a result, the body and mind can take a massive hit, and challenging symptoms—including menstrual irregularities, abnormal labs, sleep problems, gastrointestinal complaints, fainting, and poor immune functioning—often follow.

For someone with distorted eating patterns, food is often associated with something bad. As a result, it is feared and avoided at all costs. A mindset shift must take place where individuals view food as medicine rather than an obstacle. Hippocrates was on to something when he said: “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” Healthy proteins, fats, and organic vegetables are not something to be feared, but embraced.

To prevent or treat symptoms associated with your child’s distorted eating patterns, promote a view of food as medicine and educate your child on how certain foods can nurture and support key bodily functions. Individuals with eating disordered behaviors often seek out the “healthiest” option already, but often misunderstand what is actually healthy. Rather than fighting against your child’s desire for “health,” help him or her redefine what “health” is, and encourage wholesome foods that will fuel the body and mind.

Fortunately, once a nutrient-rich diet is maintained, many of the unhealthy obsessions and cycles of eating disordered behaviors may decrease. Try bringing your child on grocery shopping trips and allow him or her to cook a wholesome family meal. Encourage mindful eating practices that focus on listening to the body and eating until full. During the early stages of treatment, remove or cover all labels in your kitchen, and focus instead on the freedom that comes with letting go of caloric control and gifting the body with foods it needs most.

Getting at the Roots: Assessing Your Child's Physiology

Contrary to popular belief, eating disorders are not just in one’s “head,” but may have roots elsewhere in the body. Psychological and environmental factors are known to “pull the trigger” for eating disordered behaviors, but under the surface, deeper issues are often at play.

Some of these issues include genetic and biological factors that predispose individuals towards these eating disordered behaviors. Nutrient deficiencies, blood sugar imbalances, and food sensitivities are also often observed in patients receiving treatment (Achamrah et al., 2017; Birmingham & Gritzner, 2006; Mehler & Brown, 2015; Shay & Mangian, 2000).

Symptoms of nutrient deficiencies can manifest long before the distorted eating patterns emerge. For example, zinc deficiency is one nutrient imbalance observed in patients with anorexia nervosa (Greenblatt & Delane, 2018; Shay & Mangian, 2000). Common features of zinc deficiency include poor growth, weight loss, skin abnormalities, amenorrhea and depression, which are often found among eating disorder populations. Magnesium deficiency is also seen in patients with eating disordered behaviors, which could be a cause or effect of the eating disorder (Hall et al. 1988). In addition, researchers have established an association between anorexia nervosa and celiac disease, which can lead to misclassification and improper treatment if unaddressed (Mårild et al., 2017).

Disordered eating patterns can also contribute to nutrient deficiencies, which can begin early in childhood. Kids and teens may feel pressured to adopt a certain exercise routine, limit caloric intake, and/or pursue a specific weight. Excessive dieting begins and sooner than later, you’ve got a hypoglycemic teenager with chronically low nutrient levels. Things can get out of hand pretty quickly, therefore it's important to take action fast. Set up an appointment with a qualified practitioner who can perform thorough biomedical testing, provide appropriate supplementation, and/or direct you and your child towards an optimal meal plan.

Getting at the Roots: Prioritize Consistent Therapy

In addition to connecting with the right medical provider, it’s important to seek out regular therapy. There is a strong connection between trauma and eating disordered behaviors, and many people with these conditions also struggle with issues related to perfectionism, poor body image, addiction, anxiety, and depression. While functional medicine can provide a degree of relief for these conditions, further work is often needed to address the underlying traumas or faulty thinking patterns associated with these conditions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, mindfulness, group therapy, and family therapy have been helpful in addressing these psychological roots. Not all clinicians have the skill set to treat eating disordered behaviors, however, as these conditions can be very complex and challenging to treat. If possible, find a clinician who is a certified eating disorder specialist (CEDS), as these clinicians have received specialized training in treating individuals with eating disordered behaviors.

In addition, I always recommend the books, Life Without Ed by Jenni Shaefer, and Eight Keys to Recovery by Carolyn Costin. These are both remarkable books and will serve you and your child well.

Be Your Child’s Biggest Role Model

Parents, believe it or not, you are a child’s biggest role models. Children and adolescents are generally more affected by what their parents do than by what they say. Therefore, it’s important for you to address any behaviors associated with food or weight that could send mixed messages.

For example, do you express negative self-talk associated with your body or weight in front of your child? Do you ever talk about how “fat” you are, or complain about the way your body is shaped? Do you attempt to stuff your own feelings down with food, or to restrict food as a method of control? Let me clarify, I’m not implying that eating disordered behaviors are caused by parents. There are many parents out there who do serve as amazing role models. It’s important to keep this in mind, though, especially if you are struggling with some of these areas yourself. You can’t expect your child to change his or her own eating disordered behaviors if you are not willing to change your own.

Reflect on your relationship with your own body, re-evaluate what and how you eat, and consider the potential impact this may have on your child. Be mindful of your own words; for children and adolescents are extremely good listeners and can pick up on conversations you thought you’d kept to yourself.

Be Your Child’s Biggest Support

Parental guidance and support is a key element for individuals recovering from eating disordered behaviors. Without active parental involvement and support, children and adolescents can struggle to implement changes on their own, and may lack the accountability they desperately need. While there are multiple ways you can support your child, here are a few suggestions:

- Encourage conversation around personal triggers or stressors, but don’t push or force.

- Hold your child accountable to his or her meal plan, but don’t demand or coerce.

- Prioritize family meals and model mindful eating practices.

- Destroy all scales – do not leave them in your home.

- If weight gain is a goal, schedule regular shopping sprees for new clothes, and frequently dispose of your child’s old, tight-fitting clothes.

- Refrain from commenting on your child’s body weight or appearance during treatment. For many individuals, even pleasant comments, such as “you look really healthy,” could serve as triggers.

- Assist your child in redirecting the obsessions over food or weight to other areas that may provide a deeper sense of meaning or fulfillment (e.g. music, spirituality).

- Exercise with your child in enjoyable ways.

- Encourage discussion of the feelings behind your child’s behaviors, not just the behaviors themselves.

- Emphasize and praise your child’s unique interests, talents, and inner attributes on a regular basis.

- For additional support, look into a peer-to-peer parenting support group in your area. These groups provide support directly to parents who are struggling with these issues.

Be Patient, and Accept Your Limits

Full-fledged eating disordered behaviors don’t start overnight, and they won’t stop overnight. The length of time for recovery can depend on many different variables, but it may often take years before one is considered “fully” recovered. Change of any kind can take time, and this process is no exception. Embrace baby steps while keeping the bigger picture in mind. Relapses will happen, but they don’t have to steer you or your child off course.

Ultimately, this is your child’s journey, and she will have to decide for herself how she will face and overcome this struggle. It’s important to give your child the space needed to make her own decisions, while empowering her through the process.

Always remember, freedom is possible. It's often a brutal war, but one worth fighting. Whatever you do, don’t lose hope. Your child needs you.

©2020 Elizabeth Dixon, LISW-CP. All rights reserved.

References

Achamrah, N., Coëffier, M., Rimbert, A., Charles, J., Folope, V., Petit, A., Déchelotte, P., & Grigioni, S. (2017). Micronutrient Status in 153 Patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients, 9(3), 225.

ANAD (2019). Eating Disorder Statistics.

Birmingham, C.L., Gritzner, S. (2006). How does zinc supplementation benefit anorexia nervosa? Eat Weight Disord 11, e109–e111.

Greenblatt, JM., & Delane, DD. (2018). Zinc Supplementation in Anorexia Nervosa. J Orthomol Med. 33(1)

Hall, R., Hoffman, R., Beresford, T., Wooley, B., Tice, L., Hall, A. (1988). Hypomagnesemia in Patients with Eating Disorders. Psychosomatics 29 (3), 264-272.

Mårild, K., Størdal, K., Bulik, C. M., Rewers, M., Ekbom, A., Liu, E., Ludvigsson, J. F. (2017). Celiac Disease and Anorexia Nervosa: A Nationwide Study. Pediatrics, e20164367.

Mehler, P. S., & Brown, C. (2015). Anorexia nervosa - medical complications. Journal of eating disorders, 3, 11.

Shay, N. & Mangian, H. (2000). Neurobiology of Zinc-Influenced Eating Behavior. The Journal of Nutrition, 130 (5). 1493S-1499S.