Psychiatry

A Brief History of Psychiatry

The history of psychiatry reflects paradigmatic shifts in the history of ideas.

Updated June 23, 2024

Our understanding of mental illness has changed dramatically in recent times and is continuing to evolve. A look at the past can cast equal measures of doubt and enlightenment.

In antiquity, people did not think of ‘madness’—a term that they used indiscriminately for all forms of psychosis—in terms of mental disorder, but more in terms of divine punishment or demonic possession. Evidence for this comes, among others, from the Old Testament, and most notably from the First Book of Samuel, according to which King Saul became ‘mad’ after neglecting his religious duties and angering God.

That David played on his harp to appease Saul suggests that, even in biblical times, people understood that psychotic illnesses could be successfully treated:

But the Spirit of the Lord departed from Saul, and an evil spirit from the Lord troubled him… And it came to pass, when the evil spirit from God was upon Saul, that David took an harp, and played with his hand: so Saul was refreshed, and was well, and the evil spirit departed from him.

—1 Samuel 16:14, 23 (KJV)

In Greek mythology and the Homerian epics (circa eighth century BCE), madness is similarly thought of as a punishment from God—or the gods. Thus, Hera punishes Hercules by ‘sending madness upon him’, and Agamemnon confides to Achilles that ‘Zeus robbed me of my wits’.

It is not until the time of Hippocrates (d. 377 BCE) that madness first became an object of scientific speculation. Hippocrates taught that madness resulted from an imbalance in four bodily fluids or ‘humours’. Melancholy, for instance, resulted from an excess of black bile [Greek, melaina chole], and could be cured by such ‘restorative’ treatments as special diets, purgatives, and bloodlettings.

To modern readers, Hippocrates’ ideas may seem far-fetched, perhaps even on the dangerous side of eccentric, but in the fourth century BCE they represented a significant advance on the idea of madness as divine punishment or demonic possession:

Only from the brain springs our pleasures, our feelings of happiness, laughter and jokes, our pain, our sorrows and tears … This same organ makes us mad or confused, inspires us with fear and anxiety…

—Hippocrates, The Holy Disease

Aristotle and, later, the Roman physician Galen (d. c. 210 CE) elaborated upon Hippocrates’ humoral theories, and helped to establish them as Europe’s dominant medical model.

Not all minds in Ancient Greece thought of ‘madness’ as a curse or disease. In the Phaedrus, Plato quotes Socrates as saying that madness, ‘provided it comes as the gift of heaven, is the channel by which we receive the greatest blessings… madness comes from God, whereas sober sense is merely human.’

The Roman Empire

In Rome, the physician Asclepiades (d. 40 BCE) and the statesman and philosopher Cicero (d. 43 BCE) rejected Hippocrates’ humoral theories, advancing, for example, that melancholy results not from an excess of black bile but from emotions such as rage, fear, and grief.

Cicero’s questionnaire for the assessment of mental disorders bore remarkable similarities to today’s psychiatric history and mental state examination. Used throughout the empire, it included, among others, sections on habitus (‘appearance’), orationes (‘speech’), and casus (‘life events’).

Unfortunately, the influence of these luminaries began to decline in the first century CE, and the physician Celsus (d. 50 CE) sought to re-establish the idea of madness as a punishment from the gods—an idea which returned to currency with the fall of Rome and rise of Christianity.

The Middle Ages

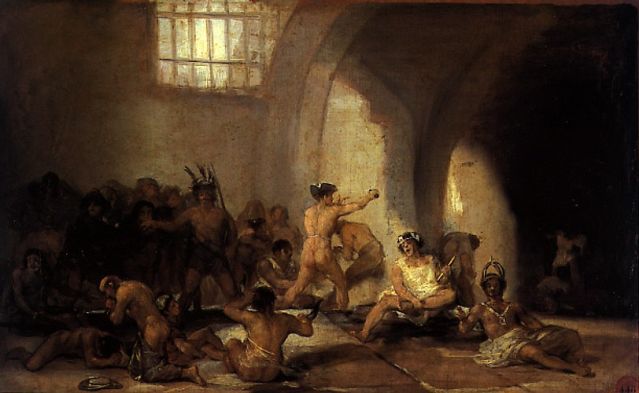

In the Dark or Middle Ages, religion became central to cure, and, alongside the mediaeval asylums such as the Bethlehem (a famous or infamous asylum in London that is at the origin of the expression, ‘like a bad day at Bedlam’), some monasteries transformed themselves into centres for the treatment of mental disorder. This is not to say that the humoral theories of Hippocrates had been supplanted, but merely that they had been incorporated into the prevailing Christian dogma, with older treatments such as bleeding, cupping, and leeching continuing alongside the prayers and confession.

Classical ideas from the Golden Age of Athens had been kept alive in Islamic centres such as Baghdad and Damascus, and their re-introduction to Christendom by the theologian St Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) and others in the thirteenth century once again led to a separation between mind and soul, and to a shift from the Neoplatonic metaphysics of Christianity to the Aristotelian empiricism of science. This movement laid the foundations for the Renaissance, and, later, for the Enlightenment.

The Renaissance

The burning of the so-called heretics—often people suffering from psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia—began in the early Renaissance and peaked in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

First published in 1563, The Deception of Demons [De præstigiis dæmonum] argued that the madness of ‘heretics’ resulted from natural rather than supernatural causes. Not content with proscribing the book, the Church accused its author, Johann Weyer, of being a sorcerer.

From the fifteenth century, scientific advances such as the anatomy of Vesalius (d. 1564) and the heliocentric system of Galileo (d. 1642) began challenging the authority of the Church, and the centre of attention and study gradually shifted from God to man and from the heavens to the Earth.

The Enlightenment

Despite the scientific developments of the Renaissance, the humoral theories of Hippocrates perdured well into the nineteenth century, to be lampooned by the playwright Molière (d. 1673) in such works as The Imaginary Invalid [Le Malade imaginaire] and The Doctor in Spite of Himself [Le Médecin malgré lui]. In the 1830s, France alone imported around forty million leeches a year for medicinal purposes.

Empirical thinkers such as John Locke (d. 1704) in England and Denis Diderot (d. 1784) in France challenged this status quo by arguing, in the same vein as Cicero, that reason and emotion are a product of the senses. Also in France, the physician Philippe Pinel (d. 1826) began to regard mental disorder as the result of exposure to psychological and social stressors, and, to a lesser extent, of heredity and physiological damage.

A landmark in the history of psychiatry, Pinel’s Treatise on Insanity [Traité Médico-philosophique sur l'aliénation mentale…] called for a more humane approach to the treatment of mental disorder. This so-called moral treatment included decreased stimuli, routine activity and occupation, and a trusting and confiding doctor-patient relationship. At about the same time as Pinel in France, the Tukes (father and son) in England founded the York Retreat, the first institution ‘for the humane care of the insane’ in the British Isles.

The Modern Era

In the nineteenth century, hopes of successful cures lead to a burgeoning of mental hospitals in North America, Britain, and many other parts of Europe. Unlike the foreboding mediaeval asylums, these hospitals treated the ‘insane poor’ according to the principles of moral treatment.

Like Pinel before him, Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol, Pinel’s student and successor at the Salpêtrière in Paris, attempted a classification of mental disorders, and his resulting Concerning Mental Illnesses [Des Maladies mentales...] is regarded as the first modern treatise on clinical psychiatry.

Half a century later, Emil Kraepelin published his landmark classification of mental disorders, the Compendium of Psychiatry, in which he isolated schizophrenia (or dementia præcox, as he called it) from other forms of psychosis.

Kraepelin further distinguished three clinical presentations, or variants, of schizophrenia:

- Paranoia, dominated by delusions and hallucinations;

- Hebephrenia, dominated by inappropriate reactions and behaviours; and

- Catatonia, dominated by agitation or immobility, together with odd mannerisms and posturing.

In the early twentieth century, the psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers (d. 1969) brought the methods of phenomenology—the direct investigation and description of phenomena as consciously experienced—into the field of psychiatry. This so-called descriptive psychopathology created a more objective foundation for the practice of psychiatry by emphasizing that symptoms of mental disorder ought to be diagnosed on the basis, not of their content, but of their form. This means, for example, that a belief is a delusion not because it is deemed implausible by a person in a position of authority, but because it conforms to the formal definition of a delusion, namely, ‘a strongly held belief that is not amenable to reason and that is out of keeping with its holder’s background or culture.’

Sigmund Freud (d. 1939) and his school influenced much of twentieth century psychiatry, and by the second half of the century a majority of psychiatrists in the US had come to believe that mental disorders such as schizophrenia resulted from unconscious conflicts originating in childhood. As a director of the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) put it, ‘From 1945 to 1955, it was nearly impossible for a non-psychoanalyst to become a chairman of a department or professor of psychiatry.’

In the latter half of the twentieth century, genetic studies, neuroimaging techniques, and pharmacological developments such as the first antipsychotic drugs completely overturned this psychoanalytical model of mental disorder, prompting a return to a more empirical ‘neo-Kraepelinian’ model.

At present, mental disorders are primarily seen as a biological disorder of the brain, although it is also recognized that psychological and social stressors can play important roles in triggering episodes of illness, and that different approaches to treatment should be seen not as competing but as complementary.

Even so, critics deride this ‘bio-psycho-social’ model as little more than a ‘bio-bio-bio’ model, with doctors and psychiatrists reduced to mere diagnosticians and pill pushers. Many critics question the scientific evidence underpinning such a robust biological approach, and call for a radical rethink of mental disorders, not as detached disease processes that can be carved up into diagnostic labels, but as subjective and meaningful experiences grounded in personal and larger sociocultural narratives.

Read more in The Meaning of Madness.