Bias

The Fawn Response to Racism

Part 1: A reflection on POC strategies to mitigate violent oppression.

Posted April 30, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- A therapist named Pete Walker originally coined the term “fawn response” to describe a strategy children use to survive parental abuse.

- The fawn response develops when fight and flee strategies escalate abuse, and freeze strategies don't provide safety.

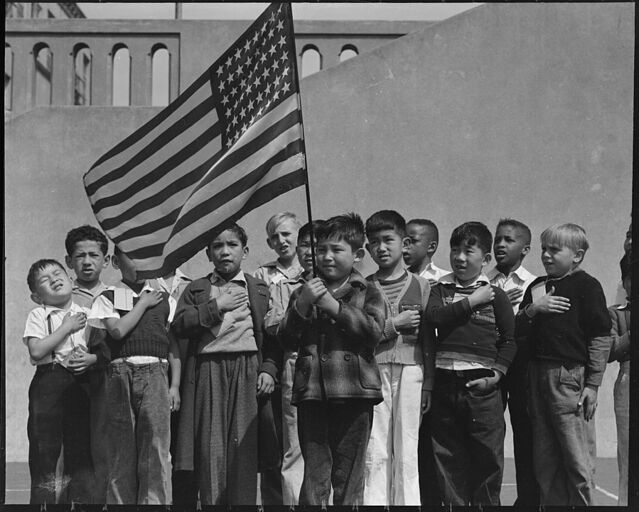

- People of color were forced to use fawn strategies to survive the traumas and dangers of white racial violence and terrorism.

- The model minority narrative (to assimilate, be useful, be a role model and not a threat) is a common manifestation of the fawn response.

A therapist named Pete Walker originally coined the term “fawn response” to describe a pattern he observed in how his patients coped with childhood abuse that didn’t fit into the fight-flight-freeze model. This 4th strategy involved proactively appeasing the abuser by being useful and helpful in order to gain a modicum of safety. Walker chose this name based on the definition of the word “fawn” from Webster’s dictionary: “to act servilely; cringe and flatter.”

How the fawn response develops

In a 2003 article, Walker explained that the fawn response develops when an abused child learns that fight and flee strategies escalate the abuse, and freeze strategies don’t offer any safety. Walker explained, “protesting abuse leads to even more frightening parental retaliation, and so [the child] relinquishes the fight response, deleting ‘no’ from her vocabulary and never developing the language skills of healthy assertiveness. (Sadly, many abusive parents reserve their most harsh punishments for ‘talking back,’ and hence ruthlessly extinguish the fight response in the child.)”

Walker also explains that the child learns that “her natural flight response exacerbates the danger” when the abuser says, ”I’ll teach you to run away from me!” and lashes out violently. He also shared that for many children, “the ultimate flight response, running away from home, is hopelessly impractical and ... even more danger-laden.” Freeze strategies involve numbing and dissociation to cope with the abuse, but do not actually provide any protection from abuse. Therefore, as an alternative survival strategy, the abused child “learns to fawn her way into the relative safety of becoming helpful.”

The fawn response and POC

I believe the fawn response is very important to understanding the strategies available to earlier generations of people of color (POC) to survive the traumas and dangers of living in a white supremacist society that for hundreds of years gave white people free rein to seize POC land, vandalize their property, enslave or exploit their labor, abuse and lynch their bodies, and degrade their dignity. I also believe understanding the fawn response is still relevant to POC today as we process the historical traumas of our ancestors and predecessors while we grow up, go to school, build careers, and raise families in an era when institutions led by white people have the power to act as gatekeepers that determine where we can rent or buy homes, what schools we can go to, what jobs we can get, how much we get paid, whether we advance through promotions, and how much capital we can access to buy real estate or build businesses.

As a general historical pattern, POC came to America, voluntarily or involuntarily, to fill a need for cheap labor in agriculture, factories, and railroad construction. The African slave trade was the primary source of cheap labor for the American South up through the end of the Civil War. Once slavery was abolished, business owners ramped up the recruitment of migrants from Asia to fill labor shortages. For instance, the Central Pacific Railroad at one point had about 12,000 Chinese laborers work on constructing the transcontinental railroad, making up 80% of its workforce. Hawaii’s sugar plantations and California’s agricultural industry were originally built by laborers recruited from China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines.

In most cases, white bosses abused and exploited these immigrant laborers similarly to how Southern plantation owners treated former slaves. Whites in power segregated the POC into dilapidated housing quarters, restricted their movement, and excluded them from whites-only churches, schools, hospitals, and social spaces. Until the 1960s, white mobs were given impunity to terrorize, attack, and even lynch any POC whom they felt needed to be taught a lesson or made an example of without fear of prosecution.

Similar to Walker’s framework for how abused children are forced to bypass fight, flee, or freeze strategies, the white power structure limited the ability of POC to use fight, flee, and freeze strategies to navigate racial violence, racist laws, and exploitative labor practices. The “fight” response among POC was contained through state-sanctioned violence at both the individual level through bullying and vigilante-style executions and at a community level through massacres and the razing of entire POC communities, such as the 1871 massacre of Chinese in Los Angeles (possibly the largest mass lynching in US history), the 1890 massacre of Native Americans at Wounded Knee, and the 1921 massacre of the African American community in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The white power structure contained the “flee” response among slaves through severe punishment, including execution, of captured runaway slaves and of those who tried to help a slave run away. After the Civil War, the South contained the flee response by instituting Black Codes and Vagrancy laws to trap generations of freed slaves into serving as cheap laborers for the sharecropping system and the convict leasing system. Outside the South, segregation, curfews, and documentation requirements imposed on POC contained the flee response by delineating specific areas where POC were allowed to work, live, and socialize, and specific hours and modes by which they could travel.

The need for cheap labor also contained the "freeze" response among POC by requiring laborers to work exhausting schedules with little pay, and hardly any leisure time for rest, recovery, and personal development, and education. Today, mass incarceration and probation provide a modern mechanism for policing and containing fight, flee, and freeze responses among communities of color.

When fight, flee, and freeze strategies did not lead to safety or protection, POC were forced to resort to fawn strategies. In this light, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s infamous “Uncle Tom” character may actually be an archetype for a fawn strategy that slaves used to build relationships with slave owners and mitigate the violence and abuse to which they and their loved ones were subjected. Booker T. Washington’s advocacy of a "go slow" approach, often criticized as the “Atlanta Compromise,” to avoid a harsh white backlash can also be seen as an adaptive fawn response to the outbreaks of brutal racial violence that reversed the economic and political advancement of Blacks during Reconstruction. Even the “Talented Tenth” argument set forth by W.E.B. Du Bois can be seen as a manifestation of a fawn strategy, in which the most talented 10 percent of the Black community are tasked to excel as role models academically, economically, and civically within a white power structure, so they can use their position and influence to lift up the rest of the Black community.

In fact, the most common manifestation of the fawn response among POC is probably the internalization of the model minority narrative, which appears to be universally pervasive among all POC communities. This narrative involves assimilating and complying with the rules set by dominant white culture to such a degree that white gatekeepers don’t see the non-white person as a threat and may even view that person as an “honorary” white person, so long as they reflect back to white gatekeepers their notion of “a good Black person,” a “good Asian person,” a “good Mexican person,” a “good Native American,” etc.

However, POC who rely on the model minority narrative eventually learn the harsh lesson that how they are perceived by white people is not actually within their control. In times of recession and economic scarcity, xenophobic foreign policy, and war, even the most accomplished model minorities can be seen as threats, dehumanized, scapegoated, and attacked. During World War II, model minorities among Japanese Americans were still placed in concentration camps. In 2021, model minorities among Asian Americans, such as doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers on the frontlines of the fight against COVID-19 must still grapple with anti-Asian racism from patients, colleagues, and neighbors.

In my next post in this series, I will share reflections on how I’ve internalized the model minority narrative to gain upward mobility in American society by trying to be a superhuman overachiever. I will also try to identify fawn response patterns I’ve used while following this narrative that are maladaptive as well as the healthier behaviors I’m building to replace these maladaptive patterns.

References

Pete Walker. “Codependency, Trauma and the Fawn Response,” The East Bay Therapist, Jan/Feb 2003, http://www.pete-walker.com/codependencyFawnResponse.htm.

Erika Lee. The Making of Asian America: A History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2010.

Public Broadcasting Service (U.S.), et al. Reconstruction: America After the Civil War. Arlington, Va: PBS, 2019.

Public Broadcasting Service (U.S.), et al. Asian Americans. Arlington, VA: PBS, 2020.

Ava Duvernay, and Jason Moran. 13TH. USA, 2016.