Health

"Mental Health Matters" Isn't Enough

It's not just what's in your head that shapes your wellbeing.

Posted October 11, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Individual health is not solely determined by biological or behavioral factors within one’s control but also by a layer of interacting systems.

- Certain social, societal, and natural environments can be either more or less conducive to mental health.

- Mental health is physical health and vice versa. It is not simply a cluster of unwanted feelings or self-deprecating thoughts.

Yesterday was World Mental Health Day. Businesses globally touted the importance of how much “mental health matters.” While awareness of mental health as an influential factor in health more broadly is a necessary step toward eliminating the stigma which accompanies help-seeking behaviors, there seems to be little acknowledgment of how contextually embedded mental health actually is.

The social-ecological model of health

The social-ecological model of health is one model proposed over three decades ago by public health scientists. It has increasingly received more attention, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and societal injustices which continue to be perpetuated around the globe, such as the recent death of Mahsa Amini in Iran or police brutality against Black Americans like George Floyd in the United States.

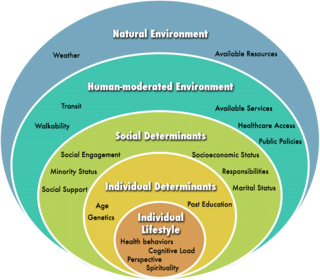

According to this model, individual health is not solely determined by biological or behavioral factors within one’s control but is also influenced by a delicate collection of interacting systems at various levels including interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy which can be a source of stress or resilience.

What this means, in effect, is that individual lifestyle factors such as health behaviors, exercise, cognitive load, mindset, and spirituality which are ripe for intervention are but one layer of a complex web resulting in a person’s mental health status. Older or younger age, lack of education, and genetics are individual determinants of health that can also be acted upon to improve one’s mental health, such as through providing health education tools to communities at higher risk of developing mental or physical health problems. Beyond individual lifestyle and intrapersonal factors are the social, societal, and natural environments that are either more or less conducive to mental health.

For instance, people who identify as part of minority status in the U.S. (e.g. usually those who do not fit the mold of a heterosexual, White, cisgender, middle-class, or above male) may struggle more with their mental health due to lack of social support, social engagement, socioeconomic status, increased responsibilities, marital status, and more. Those who live in food deserts, who are unemployed, have limited healthcare access, lack transit options, and have limited public spaces with safe walkability are also at risk for mental health challenges simply due to the nature of their human-moderated environment. Lastly, the natural environment is a factor in mental health too, which includes pieces of the puzzle like natural disasters which befall a specific geographic region, epidemics, pandemics, and naturally-available resources like fresh water access.

All of that is to say, mental health is more than just what’s in your head. It’s shaped by your personal history, your finances, your chosen behaviors, the people you surround yourself with, your community, your geographic region, and global events. Many of these layers go beyond what's in one's control and in fact, are out of the person's control and require systemic changes and overhauls to ameliorate. Mental health is physical health and vice versa. It is not simply a cluster of unwanted feelings or self-deprecating thoughts.

Though all of these additional layers contributing to mental health may appear bleak, by acknowledging the real challenges which exist, communities may be uplifted and empowered. Accurate awareness, though uncomfortable at times, is one step closer to problem-solving and creating generalizable interventions that can not only withstand socio-ecological challenges but reshape the landscape of these environments to create a more proactive and equitable health environment for all.

References

McLeroy, K.R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education. 15:351–77.