Empathy

What Can You Do to Nurture Your Child’s Empathy?

12 ways to help your child understand, feel, and respond to others’ pain.

Posted November 2, 2019 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

No matter how naturally empathetic your child is—and some children can appear quite impervious to others’ suffering—they can learn to see another’s perspective, and to respond appropriately to others’ emotions and behaviours. Here are some ways you can help your child learn to be more empathetic:

- Model how to value feelings. Show warmth, respect, and empathy towards your child and others. Acknowledge and value people’s feelings in your child’s presence (and elsewhere!). Be understanding and sympathetic when someone is sad, upset, distressed, or frustrated. Speak about others with kindness and respect, even when you think your child isn’t listening.

- Express your feelings openly. If you are having a hard day, or are feeling something strongly—whether good or bad—tell your child. Their reactions might surprise you, and you will be helping them recognize and respond to the emotions of others.

- Support your child’s self-regulation skills. It hurts to feel someone else’s pain, so it’s natural for your child to back away from experiencing and caring about others’ pain. They’ll have an easier time overcoming that impulse if they feel secure, and are able to manage their own emotions. If your child knows they can count on you for emotional and physical support, they will find it easier to regulate their own behaviour, and to feel concerned about others.

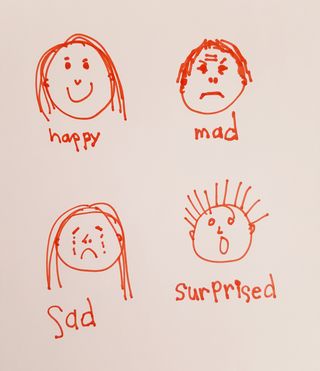

- Teach your child the language of empathy. Stand together in front of a mirror. Take turns making and copying faces, naming the emotions you’re representing: sadness, anger, surprise, disappointment, happiness, anticipation, etc. Take pictures of your child making different faces. Print the photos and emotion-label each one. Make a book of emotions together, using these photos or pictures you’ve found elsewhere. Make a chart and post it to a wall or the fridge. Don’t correct or criticize your child if you have a different opinion about the meaning of a certain facial expression or behaviour, but rather state the way you see it, and tell them that there isn’t a right answer: the only way we ever know how someone is feeling is to ask them. Each of us gets to own our internal realities, very much including our thoughts and feelings.

- Acknowledge your child’s feelings. Show your child you know and care how they feel. “I can see you’re disappointed we aren’t going to the park after school today.” “You must be sad your model broke.” “It looks like you’re happy about the dance class.” Avoid dismissive quick fixes like solving the problem yourself, or telling them everything will be all right.

- Encourage open dialogue. If your child is distressed, ask them what would make them feel better. Do some problem-solving together until they’re finished with that process. When others are distressed, ask open-ended questions that encourage your child to think about meaningful ways to help. “How can we help Sandelle feel better about her broken model?”

- Point out the feelings of others. “I think Janine is sad because she lost her ball.” “Ibrahim looked happy when his mother arrived early.” You can do this with fictional characters, as well as with people in your life. Help your child see the common humanity we all share, regardless of differences.

- Connect feelings, thoughts, and behaviours. When talking about feelings, connect them with behaviours, so that they can see cause-and-effect relationship. For example, “Joey’s feeling sad because Oscar took his truck. What might help Joey feel better?” You can also do this through stories and role-playing, both in fiction and real life. Make connections between emotions your child is seeing in others and experiences they’ve had.

- At the end of each day, ask your child about acts of kindness. In addition to asking them about other achievements and experiences, include a question about acts of kindness they might have observed or participated in.

- Create a climate of empathy at home. Work with your child to build an atmosphere that encourages every member of the family to be empathetic and understanding with each other. Point out how kindness begets kindness, and helps everyone. “That was so good of you to let Robin use your Lego. I bet she’ll let you use her paint set later.”

- Teach your child what happens when empathy fails. Under certain circumstances, people who are otherwise kind can engage in bullying and other unkind actions toward others. They can also stand by when others are bullied or badly treated. Help your child see the importance of keeping their empathy response on active alert. Point out instances where that is important in everyday life, as well as fiction and non-fiction you encounter.

- Expand your circle of concern. Volunteer, attend community meetings, and be sure to thank and care for others. Reach out to diverse others, across culture, race, sex, religion, and political affiliation. Whenever possible, include your child in these activities. Talk with compassion about events in the news, and ways you might be able to help. Expanding your child’s empathy circle in this way is linked with happiness, as well as academic and career success.

For More on This Topic

In Part 1 of this series, "Empathy: Where Kindness, Compassion, and Happiness Begin," I discuss the complexities of empathy, including distinguishing among cognitive, emotional, and compassionate forms of empathy.

In Part 2 of this series, "Empathy Milestones: How Your Child Becomes More Empathetic," I discuss the step-by-step process by which empathy develops, from parental attachment, through emotional sharing, to seeing oneself as a valuable member of a community.

There are some excellent school programs that support children’s empathy and foster a school-based climate of kindness, working against bullying and racism. These include Roots of Empathy and Making Caring Common.

“How Children Develop Empathy,” by Erin Walsh and David Walsh