Guilt

Oreo Thins Paradox – Why People Pay More For Less

Understanding STOP signal modulation in consumer behavior

Posted August 17, 2015

The new Oreo Thins is out.

Will American consumers “twist, lick, and dunk” (the act of taking the chocolate wafers apart with a twist, licking the vanilla cream in the middle, and dunking it in milk) the new Oreo Thins the same loving way that they savour and enjoy their beloved regular Oreo cookies?

The press is replete with doubters. A prominent NPR host complained about whether or not he would be able to engage in the famous Oreo “twist, lick, and dunk” ritual. ABC News even conducted a side-by-side comparison of the two cookies rating them on size, twistability (the thin ones broke 75% more often), dunkability (the thin ones took 18 seconds longer to get appropriately soaked), nutrition (the thin ones fared only slightly better), and taste (the regular ones had more of a nice chocolatey taste), with the original version clearly coming out on top.

On top of that, the new Oreo Thins—albeit the company doesn’t talk about it—comes with a 42% price premium over the regular “double-stuffed” Oreo cookies (i.e., a pack of Oreo Thins weighs 10.1 ounce and is priced at $5.49, a regular Oreo pack weighs 14.3 ounce and is priced at $5.49).

So would people buy the over-priced, under-stuffed new Oreo Thins?

We think chances are that many people will; here’s why:

GO & STOP Signals of Purchase Decisions

For a moment let’s step back and look at what drives purchase decisions more generally. The essence of many purchase decisions can be distilled down to two fundamental and often opposing drivers: a GO signal that motivates the person to approach and buy the product and a STOP signal that inhibits her from spending money on the product.

More specifically, the GO signal is a thought, feeling, or an unconscious response that energizes the potential buyers toward the product or service in question. It is what drives the potential buyer’s motivation to consume the product or service. The GO signal, if not inhibited by the STOP signal, will result in a purchase.

In contrast, the STOP signal is a thought, feeling, or an unconscious response that inhibits the purchase decision. It comprises all the signals that repel or hold back the potential buyer from the product or service in question.

Now what kind of GO and STOP signals would a person contemplating an Oreo cookie face?

When confronted by a tempting snack like the regular, “double-stuffed” Oreo cookies, the person gets pulled in different directions by the GO and STOP signals in her mind.

On the one hand, her intrinsic liking for these famous chocolate and vanilla cookies might trigger visceral responses–-such as salivation and hunger—motivating her to buy the regular pack of Oreos. On the other hand the anticipation of the post-consumption regret and guilt, and the likely negative feelings caused by thinking about an expansion of her waistline might trigger the STOP signal, inhibiting her purchase motivation.

We argue that it is precisely this state of dilemma caused by two conflicting signals, one driving her toward the purchase decision and the other inhibiting her purchase decision, that is likely to make the new Oreo Thins particularly appealing to her.

Oreo Thins & STOP Signal Modulation

The new Oreo Thins is a clever way to modulate the STOP signals. The “Thins” is very likely to appeal to reluctant consumers who had a visceral craving for regular Oreo cookies, but were reluctant to buy them because of their perceived unhealthiness: “I am so tempted to eat these Oreos, but I cannot because they are unhealthy and fattening!” For such customers, the “Thins” version is going to be a very appealing alternative to the regular Oreos. This is because by reducing portion size by making the cookies “thinner” and by packing in fewer calories, the marketer reduced the consumption guilt without in any way reducing the visceral appeal of the cookies. In fact, the cookie maker reassures consumers that the new cookie is, “The Oreo you love, now thinner.”

In short, the “Thins” innovation is likely to significantly reduce the guilt-induced STOP signals that were holding this consumer back from consuming the regular tasty, “double-stuffed” Oreo. By simultaneously reducing these guilt-induced STOP signals and maintaining the strength of the taste-induced GO signals, the new Oreo Thins is likely to eke out quite a consumer following.

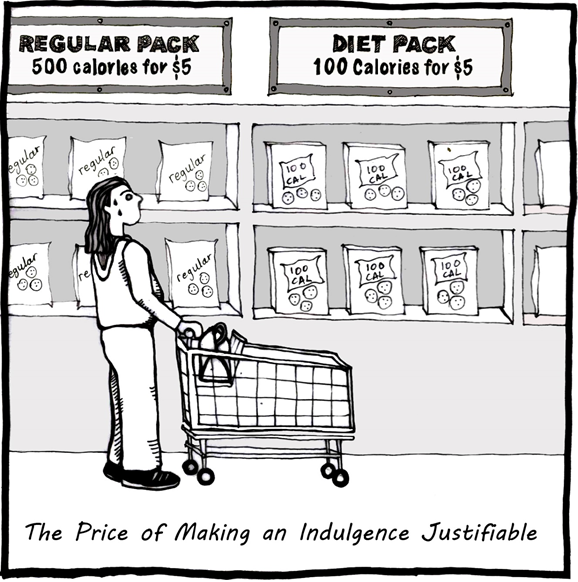

The new Oreo Thins is yet another example that attests to the power of modulating the STOP signal. In fact, it’s a snacking innovation that is not new. It’s an innovation that has quietly taken over our supermarket aisles since 2004 and we have barely noticed. It’s the 100-Calories Paradox.

The 100-Calories Paradox

In 2004, Nabisco executives introduced a new “100-Calories Pack” format for their cookies. Industry experts were deeply sceptical and thought consumers would not buy a product that was “underfilled and overpriced” especially in a food category like snacks, where purchase behavior was largely discretionary.

Defying the experts however, Nabisco’s new “100-Calorie Pack” packaging format for their cookies was an unqualified success and competitors rushed to copy them. Today practically every major food brand has a 100 calories version of their product available in the market in categories as diverse as cookies, potato chips, beef jerky, and ice creams. Sales of 100 calories packs reached $200 million annually after just three years on the market.

The success of the 100 calories packs was quite baffling when one compares the unit prices of these packs with the unit prices of regular packs. The Centre for Science in the Public Interest recently did a study that found that for some of the popular brands such as Cheese Nips, Keebler Chips, and Chex Mix, consumers are paying as much as 250%-300% more for the 100 calories pack versions. This premium is all the more baffling because, after all, transforming a regular pack to a 100 calories pack is not a daunting task. You could actually do it in your own kitchen. All that you need is a pair of scissors and a few small Ziploc-type resealable plastic bags.

The Power of STOP Signal Modulation

But if we think of cookie and other tasty snack purchase decisions in terms of the conflicting GO (i.e., taste) and STOP (i.e., guilt) signals, then the success of the 100-calorie pack should no longer be baffling. Many potential cookie consumers were torn between the allure of a great tasting cookie and the health-related drawbacks of a high-calorie snack.

The 100-calories pack was a masterful innovation that significantly dampened the guilt-related STOP signals, without altering the taste-related GO signals associated with a chocolate chip cookie. That’s why it was a runaway success. Consumers are so happy to be relieved of the guilt-induced STOP signal that was burdening them that they don’t care much about paying a hefty premium for it.

We believe that the new Oreo Thins is also likely to be accorded a warm reception by the consumers. And it will be for the same reasons because of which the 100-calories pack was a big hit. After all, the new Oreo Thins is a thinly disguised 100-calorie pack Oreo.