Health

Stigmatization of Mental Illness in Africa

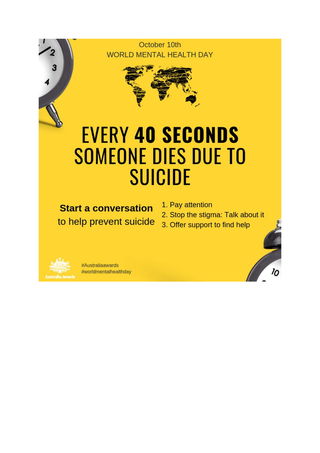

World Mental Health Day is a time to reflect on stigmatisation and human rights

Posted October 7, 2019

“I know of a 30 year old man who wanted to marry a lady of 26 years. The lady had an elder brother who had suffered a mental illness. When the man's family got to know of the family history, the whole marital process came to a halt. All because they believed the lady might bring this condition into their family” Dr Dennis B. Daliri, Ghana.

Thursday 10 October is World Mental Health Day. It is a good time to reflect on the ways in which we can contribute to our understanding of mental health, and address the general wellbeing of people in communities internationally. To this end, health workers from nine African countries recently participated in an Australia Awards Short Course, Mental Health Care in a Public Health Context , which provided professional development to promote mental health and best practice in the African context. A key component of the program was to address stigma in participants’ home countries.

In this post, I will outline some of the issues concerning equity and stigma across regions in Africa, and potential responses to mental health and stigma in the context of global health.

Stigma takes many forms in communities in Africa often involving extreme prejudice and discrimination. Within more traditional African communities, these may relate to the perceived reason the person has difficulties, the influence of forces beyond that person’s influence, such as being vulnerable to the intentions of others who may wield supernatural powers, and in some instances, to witchcraft.

People with mental illness suffer from the effects of their condition. However, their suffering is made much worse through the attitudes and prejudices of people around them and the larger community, where the community stigmatises their suffering and extends their prejudice to not only the person who is suffering but such prejudice may be extended to the whole family.

Stigma can be thought about in two ways: public stigma and self-stigma. Public stigma refers to the ways in which the general population thinks about people with mental illness, its causes, and potential responses. Self-stigma refers to the ways in which people suffering from a mental illness turn the prejudice in the community to their own understanding of themselves (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1489832/).

Both public stigma and self-stigma is associated with stereotypes held by the general population, leading to prejudice and discrimination. The history of stigma in response to mental illness is as old as human society. All these factors are likely to have a negative effect on the life of the person.

The prejudice towards people with mental illness in Africa can take extreme forms, affecting multiple aspects of the person’s life, including the very nature of their selfhood. In such instances, the person may be accused of witchcraft, they may be denied marriage opportunities, and the explanations for their behaviour may extend to all areas of their lives and in some instances lead to a process of exclusion.

Dr P Maramba, from the Ngomahuru Psychiatric Hospital, Zimbabwe, described a number of derogative terms used in his country to describe mentally ill people. These included: mupengo, benzi, anodhunya, and dununu. The ramifications are profound. He describes mental illness as being viewed as punishment by the "gods" as it is believed one has "ngozi" – that is, done something wrong or their parents have done something wrong – so relatives are fearful of associating with such a person in case they are “caught in cross fire”.

Dr. Maramba observed that mentally unwell people in parts of Africa are assumed to be violent and destructive, even within the primary health care system. He related a recent experience where a female health worker, who had a previous diagnosis if schizophrenia, was pregnant and wanted to deliver at the local clinic. However, the local midwife refused and referred her to the provincial hospital 50km away, despite the fact that this was her second pregnancy and was stable at the time.

Members of the community, who present with what we may call symptoms of mental illness are often believed to be demon possessed. Dr. P Maramba has estimated that almost 90% of people with such presentations are first taken to spiritual healers. It is worth acknowledging the complexity of processes followed by Indigenous healers, and that it is overly simplistic to think of the role of indigenous healers as “all good” or “all bad.” Notwithstanding, there are times that persons with symptoms of mental illness may be subjected to treatments we would consider unacceptable or even cruel.

Stigma is not restricted to the so-called, less well-resourced countries. It is also a reality in Australia, where most people living with mental illness experience stigma and discrimination as part of their daily lives. That is, people may not be accorded the same respect as other members of the community which in turn, leads to inequitable treatment of people with a mental illness.

Stigma within African communities has been particularly pernicious, especially when linked to the ravages associated with the presence of AIDS in low-income communities. The very process of stigmatisation can lead to mental health consequences. Noting that there are currently nearly 14 million orphans as a result of AIDS living in Sub-Saharan Africa, Cluver and Orkin (2009), undertook a study on the relationship between stigma and psychological distress. They showed that AIDS-related stigma, food insecurity, and bullying significantly increased the likelihood of psychological distress, and by implication, mental illness in young people.

Similarly, a study of internalised stigma in people living with HIV/AIDS referred to one in three participants in Southern Africa feeling dirty, ashamed, or guilty, which in turn was associated with depression.

In response to the impact of stigma, the Murray Primary Health Network (PHN) in Australia created the Stop Mental Illness Stigma Charter https://www.murrayphn.org.au/stopstigma/ to encourage people and organisations to adopt more helpful behaviours and practices where people with a history of mental illness may feel supported and understood.

The Charter contains seven commitments aimed at reducing the impacts of stigma, each of which may be adapted and have application in a global mental health context:

We will be informed We will learn the facts about mental illness to educate ourselves and those around us.

We will listen We will hear from and support those people who have a mental illness story to share.

We will be mindful of our language We will choose our words carefully and not reduce people to a label or their diagnosis.

We will be inclusive We will not exclude people with mental illness but instead learn from their experiences.

We will challenge the stereotypes We will challenge inappropriate names and descriptions of people with a mental illness.

We will be supportive We will treat people who have experienced mental illness with both dignity and respect.

We will promote recovery We will encourage help seeking behaviour and talk positively about regaining wellness.

These principles are universal and would, where they are adopted, go some way to addressing the impacts of stigmatisation of people with mental illness.

Australia Awards Short Courses are funded by the Australian Government and administered by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. They provide opportunities for mid-career professionals to tap into Australian expertise, gain valuable skills, and forge personal and professional links. The Australia Awards Short Course, Mental Health Care in a Public Health Context, was implemented by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

References

Cluver, L. & Orkin, M. (2009) Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 69 (8):1186-93. doi: 10.1016/j