Heuristics

Avoiding Emotional Traps is Easier than You Think

Stop your heart from leading your head

Posted October 30, 2012

We all like to think of ourselves as logical creatures. Whether it’s deciding which groceries to stock our shelves with, which cars to buy, or even which way to get where we need to go, most adults pride themselves on their ability to use logic. However, not only are our logical processes often swayed by the way problems are presented to us, but our emotions can further confuse and confound us.

Psychologists speak of “heuristics,” which are shortcuts in thinking that we use to get quickly to a solution. Imagine that you’re trying to solve an anagram. It’s pretty easy to use trial and error when you’re dealing with only a few letters (e.g. “YOU”), but as soon as you’ve got 7, 8, or 9 letters to unscramble, trial and error could take you a very long time (e.g. “VERAUNTDE”). You’ll need a heuristic such as “RE” often go together as do “A” and “D.” Using such rules of English words, you’ll more easily and quickly arrive at the solution (“ADVENTURE”).

Heuristics can save time, then, but they might lead you to make errors. In a previous blog post, I described the availability and representativeness heuristics. These are logical errors that we make because we misjudge probabilities based on what we can remember (availability) or what we think should occur (representativeness). However, there is another heuristic that can get us in even more trouble, and that is known as the affect heuristic. The “affect” in this term refers to feelings. According to the affect heuristic (Slovic et al., 2002), we make mistakes in judgments because our feelings get in the way of our rational thoughts.

When your affect heuristic goes into action, you throw your common sense logic to the winds. The basis for the affect heuristic can be traced to classical conditioning, in which you learn to associate a good feeling with some initially neutral stimulus. Advertisers use the affect heuristic all the time to get you to buy their products. The less the product has an obvious value to you, in fact, the more that advertisers manipulate your behavior through the affect heuristic. After all, why would the name of one brand of insurance appeal to you more than another? The names “Geico” and “Allstate” mean nothing in and of themselves. However, we’ve all learned to love the little Geico gecko through his many on-screen shenanigans, and so we now associate positive feelings with this insurance, if not its very funny TV ads. The phrase “15 minutes can save your life” that serves as the narrative for many of these ads is supposed to cinch the deal. Who wouldn’t spend 15 minutes to save your life?

Humor is one way that advertisers manipulate you, then, but another is a feeling of comfort and relief from worry. Allstate takes that other kind of feel-good approach. You’re in “good hands,” their ads proclaim. It might take you more than 15 mintues, but at least you’ll be taken care of, no matter what. To cinch their deal, Allstate hired the “President” of the U.S., actor Dennis Haysbert who portrayed the strong and steady David Palmer in the series “24.”. Surely, the president will stand by you, no matter what.

You can see from just these two examples that it’s pretty easy for advertisers to manipulate our buying decisions by manipulating our feelings. There are hundreds, if not thousands, more instances. The principle of behavioral marketing, in fact, can be traced to psychologist John B. Watson (of "Little Albert" fame). After being fired from his professorial job for alleged sexual misconduct, Watson went on to a highly successful career in advertising on Madison Avenue where he developed marketing campaigns based on the principles of reinforcement to get people to prefer, and then buy, a certain brand of toothpaste. Like insurance, there’s no real logical reason to prefer one brand of toothpaste over another, but if you’re made to feel good about one of them through clever advertising, that’s the one you’ll purchase.

With this explanation of the affect heuristic in mind, we can move onto the observations made by Slovic and his collaborators in showing how our heart rules our head in some not so obvious ways.

First, why do entertainers change their names? Why did Archibald Leach feel it was necessary to change his name to Cary Grant? What was so wrong with Roy Scherer Jr.’s name that he felt he needed to be called Rock Hudson? They were convinced, most likely by their agents, that the public would have a much more favorable impression of a Cary or a Rock than an Archibald or a Roy. In particular, Rock Hudson, who back in the 60s was a highly popular leading man, certainly had a name that sounded more “hunk-like” than the name his parents chose for him.

A second equally illogical use of the affect heuristic, according to Slovic and his team, involves the use of background music in movies and television. There’s no reason that the dialog can’t drive the action without a soundtrack playing as the actors are talking or a visual scene is being set. However, moviemakers know that they can put you more completely under their spell when they cue your feelings with music that matches the mood they’re trying to convey. In some cases, the music even overpowers the dialog (as happens so often in the show “Gray’s Anatomy”). The final scenes in Law and Order, similarly, play what viewers have now come to associate with ominous chords that crescendo until the suspect has no choice but to confess. For the most part, the music adds to our enjoyment, whether it’s to build the suspense or to relieve our anxiety in a romantic comedy with a feel-good ending. There's no harm in enjoying this particular affect heuristic but the fact that it works says a lot about the role of emotions in our thinking.

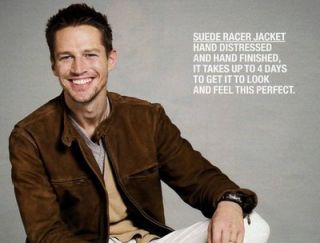

Apart from the entertainment value that the affect heuristic can produce, it can also cause us to loosen our inhibitions. As the insurance example above showed, we buy things that make us feel good. Even without directly manipulating us through advertising, however, marketers also get us to make choices by the way they show or describe their products. Slovic and his co-authors point out that this third use of the affect heuristic occurs so much that we are rarely even aware of its presence. Specifically, consider the look on a model’s face who is showing off a particular piece of clothing. Those models you see in catalogs or product websites never communicate anything other than a blissful smile. Take the smile test yourself. Go to your favorite online clothing or accessory website and look at the faces of the people wearing or using the products. Something is clearly making them laugh or at least feel excited and happy. If you buy that product you too, so your brain tells you, will share those wondrous emotions. And guess what kind of smiles the models on the Victoria’s Secret website depict? Yes, they certainly seem to have a secret which you too can ahre when you buy their scanty panties.

The affect heuristic also colors your more mundane, everyday consumer decisions. Slovic and his associates point out that the food packaging you see on the grocery store shelves is covered with affect-manipulating information. Even setting aside the photographs, it’s the words they use to describe their products that can manipulate you in very subtle ways. Just by slapping the word “improved” on a package, marketers draw your attention to it almost instantaneously. It’s a completely illogical ploy. Would a product be anything but improved? Would you ever buy something that said “downgraded”?

Oddly enough, “improved” may actually mean there’s less of the product than you could get in the old package. Other terms such as “fat free,” “natural,” or “organic” also appeal straight to your feelings. The manufacturer doesn’t even have to do anything to the actual product in some cases (e.g. carrots are fat free by definition). Yet, you’ll spend more on these supposedly healthy products which, in some cases, are no better for you than the cheaper alternatives.

These are just a few of the ways in which your heart’s feelings trump your head’s logic. There is certainly enjoyment to be had when your affect heuristic is manipulated, such as when you're watching a suspenseful thriller. However, there are also plenty of traps that can cause you to overspend or buy the product that is not the best one for you. A little psychology can go a long way in helping you make decisions that benefit your heart, your head, and the rest of your body as well.

Follow me on Twitter @swhitbo for daily updates on psychology, health, and aging. Feel free to join my Facebook group, "Fulfillment at Any Age," to discuss today's blog, or to ask further questions about this posting.

Copyright Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D. 2012

Reference:

Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, D. Kahneman (Eds.) , Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 397-420). New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press.