Identity

Why Good Philosophers Are Out of Touch with Reality

Sometimes those who know the most also know the least.

Posted July 4, 2018

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a maniac on Twitter. He verbally abuses others if he perceives them to be a fraud, a charlatan, or—one of Taleb’s best-loved slights—a “bullshit vendor.” He takes pride in this abuse, too.

A favorite of his to single out is cognitive scientist Steven Pinker. Taleb clearly hasn’t read Pinker’s Better Angels, in which Pinker argues that violence has declined over the long-term. Taleb nonetheless counters that just because violence is reduced right now doesn’t mean that it’ll stay like that in the future. A nuclear war, for example, could undo all that apparent progress. Fair point, but it’s not what Pinker argues. Pinker is concerned with analyzing historical trends, not forecasting potential doomsdays. After having done his scholarly duty in addressing the initial criticism, Pinker more or less just lets Taleb be. But Taleb relentlessly continues to go after him. And this is just one example. Taleb, it appears clear after a scroll through his Twitter feed, is a man who is out of touch with reality.

The problem is that this observation is difficult to reconcile with another facet of Taleb’s identity: He is one of the greatest living philosophers.

In 2007, Taleb published a book called The Black Swan. In it, he argues that human history is best understood in terms of its most consequential events. The thing about these events is that, once they’ve already happened, we always think we understand the causes of why they occurred. But the truth is they’re fundamentally unpredictable. We only have the illusion of understanding them. The implication, and the meat of Taleb’s book, is about how you have to expect the unexpected. That’s exactly what Taleb did when he made an insane amount of money as a trader during the 2008 financial crisis. He essentially bet that something would go wrong—because something always does—while remaining agnostic to what exactly it might be. The problem that he sets up in Black Swan he solved first in practice as a trader during the financial crisis, and then in theory as a philosopher in his subsequent book, Antifragile.

On the one hand, Taleb is a madman who seems to be living in a totally different world than everyone else. On the other hand, he seems to have an insight into the way our world works that is somehow deeper and more incisive than the rest of us. It seems like a contradiction. But I don’t think so. Rather, it’s necessary for great philosophers to be out of touch with reality in certain ways. Here’s an example.

Immanuel Kant was born in 1724 in Königsberg, then part of the Kingdom of Prussia. Kant wrote treatises such as Critique of Pure Reason and Critique of Practical Reason. He is widely considered to be one of the most influential philosophers ever. Some philosophers say that Pure Reason is right there next to Plato’s Republic as the greatest philosophical texts of all time. Whether or not that ranking is accurate, he’s clearly a guy who knew something the rest of us don’t. The peculiar thing about Kant is, purportedly, in his entire life Kant never went more than 10 miles outside of Königsberg. In other words, he couldn’t have had a smaller sliver of reality to contemplate. He was, in short, a man who was out of touch with the majority of what was going on in the world.

At first, this seems like some sort of an oxymoron. But it actually makes sense. Reality is complicated. And if you actually were to consider everything that happens in the world in its full breadth, you’d be overwhelmed. There’s just too much going on to be utterly convinced about any single interpretation of it. In order to have the kind of resolve that Kant and Taleb have, you have to cut reality down to a portion that you can handle. Only once it’s been reduced to something manageable can you put a convincing interpretation over it.

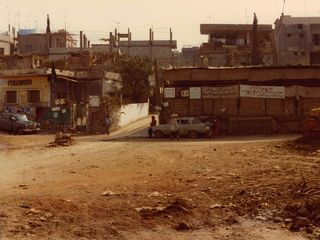

Taleb’s Königsberg was the Lebanese civil war of the 1970s and 80s. He was a young man, and he spent his formative years in a basement hearing bombs go off outside and attending his classmates’ funerals. During these years, Taleb spent a lot of time reading. What he realized was that academics who analyzed the trends of history and predicted what was going to happen next didn’t really have any better idea of what was going on than any given taxi driver you’d encounter on the streets of Beirut The events of the Lebanese civil war, he concluded, were fundamentally unpredictable. That’s why Taleb is so taken aback by Pinker’s claims (or what he interprets them to be). He’s heard those claims before: “Okay, everyone. You can come out now. The violence is over.” Or another version, “Now’s a good time to invest. The volatility is over.” But, same as Köningsberg, the Lebanese civil war is completely unrepresentative of what the world is like. It’s a very specific and biased version of reality. Taleb, in some way, really does occupy a different world than the rest of us. And it was only because of this selected version of reality that Taleb was able to develop ideas to capture what the rest of us were experiencing but couldn’t quite put our finger on.

This is also the idea behind getting a PhD, in a sense. You mark off a single piece of real estate and say, “I’m going to understand this portion of reality really well.” That comes at the expense of an understanding of the rest of the intellectual landscape. It’s not just great philosophers who are out of touch with reality, but great thinkers in general. Ultimately, it’s not a bad thing or a good thing. It’s just a tradeoff that’s inherent in the way knowledge works.