Addiction

The Case Against Adding Sexual Addiction to DSM

Despite its current popularity, sex addiction is not a mental disorder.

Posted May 31, 2019

"How convenient for the philanderer to hide behind the medical excuse. 'My addiction made me do it' is the modern equivalent and substitute for 'the devil made me do it.' Personal responsibility is easily dissolved when behavioral choices become fake psychiatric illnesses."

—Allen J. Frances, M.D., Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry, Duke University; Chair of the DSM-IV Task Force

Fads in psychiatry and psychotherapy come and go. The concepts of neurosis, hysteria, and pathologized homosexuality (to name a few) have all disappeared from the psychiatric landscape only to be replaced by the more recent fads of childhood bipolar disorder and ADHD. The latest of all diagnostic fads is sexual addiction.

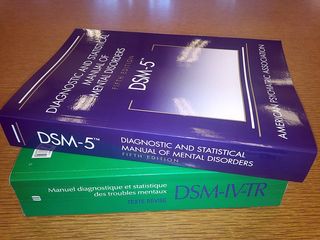

Undoubtedly, people can have problems with excessive sexual behavior. Nymphomania and satyriasis have been labels for this type of problem for hundreds of years. But recently, a small group of sex therapists and researchers, and many of their "patients," have come to push to include sex addiction (or compulsive sexual behavior) as a formal psychiatric diagnosis. However, the American Psychiatric Association has rejected these attempts, realizing the problems inherent with such a diagnosis.

Historically, the concept of addiction in medicine has been inextricably tied to the development of tolerance and withdrawal syndromes. The patient characteristically needs increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication and, upon cessation of the drug, the patient experiences (sometimes deadly) withdrawal symptoms. In recent years, however, a whole host of "behavioral addictions" have been described, including pathological gambling, internet addiction, video game addiction, and now, sexual addiction.

The concept of "behavioral addiction" blurs the line between behavior and disease. While a philosophical examination of the meaning of disease is beyond the scope of this article, suffice it to say that concept of disease has always referred to something that a person has, not something that a person does. Surely, disease can affect behavior, but it is not behavior ipso facto.

In the case of sexual addiction, few people believe that the person said to be afflicted is unable to control his behavior. To be sure, he may feel as though he is unable to control his behavior, but there is a world of difference between these two ideas. (On a related note, if it were true that the so-called sex addict cannot control his behavior, then there would be no point to "sex therapy" for the problem.)

A second, and related, problem with the pathologization of sexual behavior is the fact that any determination about the "appropriate" level of sexual interest and conduct is subject to a whole host of cultural, social, and political value judgments. What is too much sex for one person may not be enough for another, and so on. Cocaine and methamphetamine addiction exist as biological fact regardless of where you find yourself. What is called sex addiction, on the other hand, may change substantially depending on where and when one has lived.

Variations in human sexuality have long been medicalized as psychiatric diseases. Homosexuality and masturbation are two examples from the not-so-distant past. Historians of psychiatry note that many patients, in fact, were hospitalized for the dreaded condition known as "masturbatory insanity." Homosexuals were deemed mentally ill in one form or another as recently as 30 years ago.

Psychiatry has thus far heeded these warnings when it comes to sexual addiction, but the constituency for medicalization is powerful. Sex therapists have intellectual and financial investment in the addition of sex addiction to DSM, and many misbehaving patients, of course, welcome the idea as an explanation for their misconduct. In the legal realm, the concept is readily misused to keep offenders in preventive detention via sexually violent predator laws—raising serious constitutional questions.

Sexual addiction provides a convenient and medical-sounding label for a problem that has existed for thousands of years: the sexual temptations of man and woman. How it will most likely come to be used, presumably, is as an excuse for bad behavior. We don't have to look far to see it being used that way already.

For further reading, please see this article by Allen Frances, M.D., chairman of the DSM-IV Task Force, on the problems with the diagnosis of "sexual addiction," among others.

References

Frances, A. J. (2012, March 28). Do we all have behavioral addictions? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/allen-frances/behavioral-addiction_b_121…