In the middle of BBC World news is a story about a South Korean pop star turned to bodybuilding. The Korean feminine body ideal, the report reveals, has long been petite and thin, but is now changing toward a more toned physique. Although some people, the star admits, consider her a freak or ponder if she is a transsexual, she believes that the ideal is indeed changing and musculature has become more acceptable on a female body. Also, a cosmetic surgeon who has regularly performed total body liposuction and removal of a calf muscle on young women observes less need for this type of treatment. Although appearance obsessed North Americans also commonly resort to various types of cosmetic surgery, particularly facelifts, a calf muscle removal sounded a bit drastic even to me – how was one to walk after such a surgical procedure? In any case, if the BBC story is to be trusted, Korean women now exercise to build more muscle instead of removing them for sleeker looks. The final shots show the star working with weights in the gym but while defined, she does not have the muscle bulk of the women’s bodybuilders when the sport first entered popular consciousness in late 1980s. Do women continue to feel empowered to build visible muscle in North America?

The First Women’s World Bodybuilding Championships took place in 1979 in Los Angeles previous to which “the only events available for women to enter were quasi-beauty pageants added to the end of men’s competitions” (St. Martin & Gavey, 1996, p. 48). These were organized by the International Federation of BodyBuilding (IFBB, currently, the International Federation of BodyBuilding & Fitness) that is still the major association for competitive bodybuilding events, particularly in North America.

The sport of bodybuilding is unique on its focus on the looks of the body. It differs from, for example, power lifting, from which bodybuilding draws some of its participants. In power lifting the winner is determined based on the amount of weight lifted without any concern for how the lifter’s body looks. In bodybuilding the size of the muscles (not what the muscles can do) determines the winner. While there might be an element of appearance in some other sports, such as figure skating or rhythmic gymnastic, these sports do not have a focus on building muscle size similar to bodybuilding.

Many feminist researchers have mapped the psychological benefits of bodybuilding or “working out with weights to reshape the body” (Bolin, 2003, p. 110) for women. Some argue that developing a muscular body increases women’s self-esteem and confidence, because they feel more powerful, healthier, sexier, and in control of their own bodies (Grogan et al., 2004; Fisher, 1997). Similar to the BBC news report, McGrath and Chanahee-Hill (2009) and Wesely (2001) point to bodybuilding as an act against Western ideals of thinness. Furthermore, the bodybuilder’s own body image shifts toward a more muscular physique (Ian, 2001) that becomes “an expression of the will to self-construct” (Roussel & Griffet, 2000, p. 140). Heywood (1998), a bodybuilder herself, argues that a muscular body gives American women a chance to “to stand out, be above the masses, different, a star” (p. 171). Despite these feelings of personal power and masterfulness, the muscular looks, St. Martin and Gavey (1986) add, has created additional psychological work to the female bodybuilder. This is a result of psychological necessity to work on retaining the femininity of the visibly muscular body.

The ‘femininity versus muscle controversy’ was already a central feature of the 1985 semi-documentary Pumping Iron II: The Women. The film followed three women contestants, Bev Francis, Carla Dunlop, and Rachel McLish in the 1983 Ms Olympia contest. These women represented three different types of body ideals: Francis, a former power lifter from Australia in her first body building competition, had the most muscle mass; McLish, who already had several bodybuilding championships, represented the ‘early’ muscular, but slender and feminine ideal; and Dunlop, the eventual winner, was somewhere between the two others.

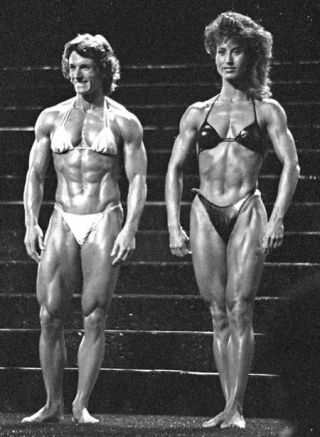

Bev Francis and Rachel McLish

While Francis had built the largest muscles, she did not win the competition. Instead, she was told to “get feminine or get out of bodybuilding” (quoted in St. Martin & Gavin, 1996). Considering that the point of a bodybuilding competition is to exhibit “the most developed and best defined muscle mass” (Ian, 2001, p. 151) such a conclusion appeared somewhat contradictory. Several researchers point out that at that point women’s physiques had grown increasingly large and instead of celebrating women’s success, the IFBB formalized ‘femininity’ as part of the judging criteria (Boyle, 2005). For example, the IFBB Professional Guidebook for Athletes, Judges, and Promoters for the 1991 Ms. International stated:

First and foremost [. . .] he/she is judging a women’s bodybuilding competition and is looking for an ideal feminine physique. Therefore, the most important aspect is shape [. . .]in regard to muscular development, it must not be carried to excess where it resembles the massive muscularity of the male physique (Cited in Ian, 2001, p. 78).

Notably, there is no ‘masculinity’ requirement for the male contestants. Feminist researchers, many bodybuilders themselves (e.g., Bolin, Heywood, Ian, Lowe, Tajrobekar), point to the contradictions embedded in the requirement to build the ideal feminine bodybuilders’ physique. They observe that building large muscles is still associated with maleness and as St. Martin and Gavey (1996) describe, the very muscular elite women bodybuilders’ bodies become to resemble the male bodybuilders’ bodies. Despite women’s own desire to build as big muscles as possible (e.g., Bolin, 2003; Boyle, 2005; Ian, 2001), there appears to be a continual pressure to balance the masculinizing effects of visible muscle mass by emphasizing the feminine. Various insignias of femininity are added (breast implants, long blond hair, feminine accessories such ear rings, visible make-up, manicured finger nails) to ensure compliance with the judging criteria and resulting competitive success. Anne Bolin, a bodybuilder and anthropologist, also points to differences in the women’s competition poses that ensure ‘feminine appeal’ as opposed to directly showing the muscle size similar to men’s poses.

When women bodybuilders proceeded to push the boundaries of building muscular bodies further, the IFBB continued to de-emphasize the muscle size in favor of symmetry, separation, and musculature (but not the extreme) in women’s competition. In 2005, IFBB introduced ‘the 20% rule’ according to which the female athletes had to decrease the amount of their muscularity by 20% for health and aesthetic reasons.

Some might consider that the professional bodybuilders have ‘gone too far’ in their muscle development that is no longer ‘natural’ and only achievable through drug use. While male bodybuilders might be charged with similar claims, women continue to negotiate the obvious biological possibility of growing a muscled female body and the social and psychological barriers of sporting such a body. These barriers are strong and many argue that women’s professional bodybuilding has been in decline since the early 2000s as it no longer attracted spectatorship. Ian, a professional bodybuilder and a feminist researcher, points out that if the IFBB does not promote women’s bodybuilding it is not going to attract spectators or sponsorship. Women’s bodybuilding, however, is not dead as the IFBB continue to organize their annual Ms. Olympia competitions.

However, there are now several categories of women’s bodybuilding. Already in 1995, ‘fitness competitions’ with lesser emphasis on muscle size were added to Ms. Olympia contests (Ian, 2001) to attract more women and more audience. Since then the IFBB has further negotiated the muscle versus femininity contradiction by adding several categories, all with reduced muscularity requirements and increased focus on ‘presentation’ (Tajrobekar, 2014), to women’s competition. Women can now compete in bikini, figure, fitness, and physique classes in addition to the Ms. Olympia competition. In their official website, the IFBB describes their women's 'disciplines' as women fitness and women's bodyfitness.

A Bodybuilder

These classes have grown in popularity even if the numbers in Ms. Olympia might have declined (Boyle, 2005).

So is women’s bodybuilding an empowering practice that improves women’s self-esteem? Based on the research, not entirely. While women bodybuilders can feel empowered to challenge the thin feminine ideal, many still struggle to get accepted. For example, one participant in McGrath and Chananie-Hill’s (2009, p. 243) study explains:

I am going to keep lifting weights and if I get bigger than I am then I won’t quit lifting just because others think I am getting too big and because society thinks it is gross or because magazines put Photoshop women on their covers for the ideal body type.

The more recent research indicates that many bodybuilders do no want to ‘look too big’ and often attribute a ‘huge’ size to unnatural steroid use. One bodybuilder explained:

I don’t use steroids so I feel like I am still considered feminine but I know there are some people who do not agree with me but I feel like I have stayed plenty feminine. (McGrath & Chananie-Hill, 2009, p. 429)

Like this participant, many believe that they can be feminine and build muscles as long as they are not too big. Another bodybuilder clarifies that ‘too big’ for her is being bigger than men:

If you’re bigger than men, to me, I would never want to look like that, it’s just too big. To me, it’s like stepping over the line between being a women and being a man. (Boyle, 2005, p. 148)

Although this assessment gives women freedom to build musculature of significant size, many bodybuilders still confront negative feedback and misunderstanding. In their study, Aspridis, O’Halloran, and Liamputtong (2014) found that even participants in a figure class with a greater emphasis on feminine presentation and considerable less on musculature faced widespread stigma and isolation.

Women's Body Fitness

In categories such as the figure class, the contestants wear high heel shoes to pose in quite sexualized positions and thus, align close to the traditional thin and toned ideal. However, these women do engage in significant training to build their physiques and while their bodies might only slightly deviate from the feminine looks, they are no longer afraid to engage in some resistance training. At the same time, the focus remains on the body’s appearance and while there is some deviation from the beauty pageants, the contestants are judged based on ‘feminine presentation.’ Women’s competitive bodybuilding with its diverse categories might serve as one way of expanding how we define the feminine body ideal, but more work needs to be done to bring more acceptance of women’s abilities to use their strong bodies in diverse ways.

Works cited:

Aspridis, A., O’Halloran, P. & Liamputtong, P. (2014). Female Bodybuilding: Perceived Social and Psychological Effects of Participating in the Figure Class. Women in Physical Activity and Sport Journal, 22, 24-29.

Boyle, L. (2005). Flexing the tensions of female muscularity: How female bodybuilders negotiate femininity in competitive bodybuilding. Women's Studies Quarterly, 33, 134-149.

Fisher, L.A. (1997). “Building one’s self up”: Bodybuilding and the construction of identity among professional female bodybuilders. In P.L. Moore (Ed.), Building bodies (pp. 135–161). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Grogan, S., Evans, R., Wright, S., & Hunter, G. (2004). Femininity and muscularity: Accounts of seven women body builders. Journal of Gender Studies, 13(1), 49–61.

Heywood, L. (1998). Bodymakers: A cultural anatomy of women’s body building. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ian, M. (2001). The Primitive Subject of Female Bodybuilding: Transgression and Other Postmodern Myths. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 12(3), 69-100.

Lowe, M.R. (1998). Women of steel: Female bodybuilders and the struggle for self-definition. New York, NY: New York University Press.

McGrath, S. A., & Chananie-Hill, R. A. (2009). Big Freaky-Looking Women”: Normalizing Gender Transgression Through Bodybuilding. Sociology of Sport Journal, 26, 235-354.

Roussel, P., & Griffet, J. (2000). The path chosen by female bodybuilders: A tentative interpretation. Sociology of Sport Journal, 17, 130–150.

St. Martin, L. & Gavey, N. (1996). Women's Bodybuilding: Feminist Resistance and/or Femininity's Recuperation? Body & Society, 2, 45-57.

Tajrobehkar, B. (2014). Book review of Strong and Hard Women: An Ethnography of Female Bodybuilding By Tanya Bunsell. Sociology of Sport Journal, 31, 377-380.

Wesely, J.K. (2001). Negotiating gender: Bodybuilding and the natural/unnatural continuum. Sociology of Sport Journal, 18, 162–180.