As I followed the recent Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia I could not help but marvel at the variety of body shapes and sizes of the athletes excelling in different sports. The long track speed skaters, whose tall bodies sported very large thighs and strong buttocks, particularly captured my attention. The streamlined, skin-tight uniforms further accentuated their extensive thigh muscles in comparison to their narrow upper bodies that did not show any visible musculature. A successful performance in long track speed skating requires very strong legs that can propel the skater, who leans forward with a deep knee bend, to maximize speed. Because the upper body is needed to generate an equal amount of force, I can understand that such a body shape is functional for this particular sport: intense training has obviously shaped these athletes’ bodies. Just attending the gym does not build a body like that, neither is it functional for most women.

I was, however, quite astounded when my brother-in-law who, after seeing professional ballet company rehearsal, commented that professional ballerinas also had ‘huge thighs and no upper bodies.’ This comment can be interpreted in at least two ways. First, the ballerinas have disproportionately small upper bodies and need to build some more upper body musculature to have a balanced looking body. Or second, their legs are too big compared to their upper bodies and thus they need to actively reduce the size of their legs. It was obvious, however, that my brother-in-law detected some imbalance in the ballerinas’ body shape.

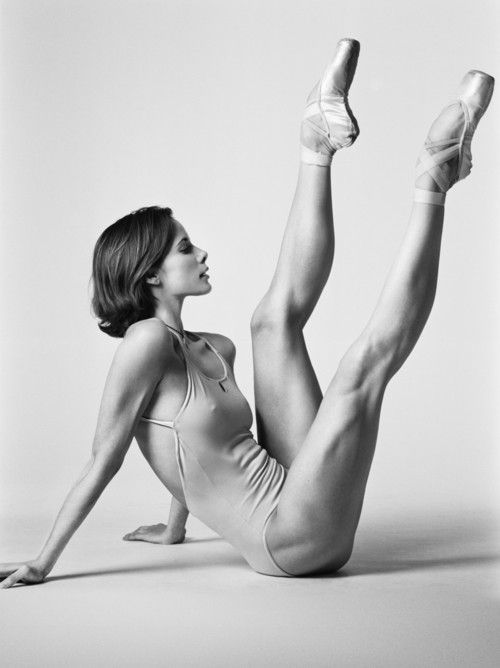

Either way, I have not found ‘huge thighs’ a common descriptor for a ballerina’s body. I had never imagined that ‘ballet legs’ had any resemblance to speed skating legs. While it might be understandable that speed skaters need their sizable thigh muscles to win races, many women want to avoid having ‘thunder thighs’—such sizable musculature is not deemed very feminine. The ballerina’s body, unlike the speed skater’s body, is often celebrated as the ideal feminine body. Her legs are much admired for their lean, sleek look and her body is considered to epitomize the beauty of the feminine body. This ballerina look can now, according to one recent fitness trend, be sculpted in fitness classes by everyone, but the results promise to differ quite drastically from the speed skater’s muscular thighs and narrow shoulders.

Popular ballet inspired workouts such as ‘Barre’ classes are now advertised everywhere. For example, an advertisement for a local Barre Studio promises to ‘build strength, flexibility, and long, lean muscles (plus a tighter tush) through a low-impact, total-body program that uses small, isolated movements.’ While the speed skaters definitely had strong ‘buttocks’ and their bodies are lean, their muscles were not best described as ‘lean.’ The recent Pilates Style Magazine announces that in addition to a lean, toned, and beautifully sculpted dancer’s body, ‘Total Barre’ delivers poise, confidence, and refined elegance. Obviously, the participants in these classes are not there to propel themselves through ice as fast as possible or even to learn how to dance—these classes are generally advertised as requiring no dance experience—but to build ‘a dancer’s body.’ None of these texts agreed with my brother-in-law’s assessment of ballet building ‘huge thighs.’ Unlike the speed skater’s body, we can all obtain long, lean muscles, poise, and elegance of ballerina in a Barre class.

Not everyone agrees with power of Barre classes to reshape our bodies into the lean dancer look. For example, Brynn Jinnett, a former New York City ballet dancer who has recently opened her own fitness studio in New York City, believes that a restrictive diet and great genes are the requirements for the ballerina’s lithe body, not ballet workouts. In addition, only with years of training are dancers able to cope with the demanding ballet positions that are likely to result in injury or are good for nothing for non-trained participants. Ballet workouts, she adds, do not typically have an aerobic component to aid in weight loss. Brynn herself subscribes to more ‘traditional’ fitness classes inspired by weight training and aerobics. Accompanying Jinnett's interview are an array of comments by readers who, while acknowledging that genetics might play some role, provided personal testimonies of how their bodies have changed as the result of ballet workouts (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2114099/Pro-dancer-says-trend…).

So, are our body shapes entirely dictated by genes? Probably not. One cannot perform ballet simply because one has a thin body. Similarly, the speed skaters are not born with their sizable thigh muscles. Although they must have some genetic qualities (such as exceptional anaerobic capacity or a large proportion of fast twitch muscle fibers — even these can be improved or changed with training), they still have to train their bodies to move a certain way to excel in their sport. The muscles that move these body parts will become stronger and grow bigger. Although some might claim that ‘ballerinas are born, not made’ few women are born with the range of motion in their joints that is required for the ballet movement vocabulary. For example, the anatomical range of motion for hip abduction (leg is extended to the side) is only about 30 degrees whereas ballerinas habitually are required to range up to 160 degrees. Mastering the ballet technique requires training from a young age. Where my brother-in-law might deserve some credit is that ballerina's movements require strong legs but do not involve much upper body strength. Her legs lift her body weight when she jumps, piruettes, or balances, but her arms are seldom used to lift more than their own weight. So, there is probably a muscle imbalance resembling the speed skater’s body. However, the ballerina’s legs perform a different and much more varied vocabulary of movements from a speed skater’s body and thus, their shape reflects the stabilization and extensions characterizing ballet.

Physical training can shape our bodies. But how easy is to obtain the shape of a ballerina’s body? Medical research suggests that ballet dancers are injury prone due to the extreme bodily requirements of ballet technique. This is because ballet movements are stylized movements that, instead of ‘natural,’ require careful training to achieve. Because the technique is difficult to master, something can easily go wrong and the ballet dancers suffer from more incidents of injuries, more severe injuries, and longer lasting injuries than other dancers. It is definitely correct to warn Barre class participants of potential injuries when attempting ballet movements without sufficient technical training.

Other research results suggest that ballerinas struggle to sustain the required low weight. They suffer from more eating disorders than other dancers, athletes, or the average population. According to a number of psychological studies conducted with dancers, constant dieting and disordered eating is extremely common in the ballet world.2 This suggests further that ballerinas are not born with the thinness required for ballet, but have to constantly maintain it through careful restrictions to their diet. Neither have ballerinas always looked the same. For example, the great ballerinas of the early 20th century, Anna Pavlova and her rival Tamara Karsavina, looked quite a bit softer than today’s skeletal ballerinas such as Darcey Bussell.

Anna Pavlova

Tamara Karsavina

Darcey Bussell

Although the movements in major classical ballets remain unchanged, the ballerina’s body shape has become thinner suggesting that the current body type is not required for the performance of ballet movements, but rather a cultural preference. This cultural preference has created a greater separation between the ideal ballet body and the size and shape of an average woman. This makes it more difficult for an average consumer to shape her body into the current thin and lithe ballerina ideal in any type of Barre class.

Several feminist dance researchers have also observed that the current ballet body is so narrowly defined that it is impossible to obtain even by the ballerinas who struggle with eating disorders and injuries. The movie Black Swan illustrated some of these problems that were further escalated by the cutthroat competition for prestigious roles and by psychological problems. Some feminist research suggests that other dance forms such as modern or contemporary dance, that are more open to diverse body types, offer a healthier chance to more women to dance while others point out that these forms are not without their problems.3

Even if the ideal ballerina’s body is quite impossible, even unnatural in its shape, and ballet movements are extremely demanding and thus, potentially dangerous, Barre classes are popular. Many participants testify for changed body shape and no one complains about building thunder thighs in a Barre class. Nevertheless, the resulting body shape does depend on what exercises are done during the class. If one’s Barre class contains movements with hand-held weights and squats, the participants train exactly the same muscles in the same way as they would in any other typical fitness class. This will strengthen the body, but not in a similar way to ballet training. To do ballet training, one needs to learn the ballet technique that shapes a slightly different set of muscles to perform a different type of muscle work. To have ‘a dancer’s body,’ one needs to perform dance movements, not simply call a squat a plié or a leg lift an attitude. Any exercise class has the potential to increase muscle strength and endurance and a Barre class can also do so. However, what exact muscles are used and how also affects the body’s ability to move in certain ways. The extensions required from ballerina are not built primarily by small isolated movements as advertised by my local Barre studio, but with a more holistic engagement of several muscle groups that work in precision using eccentric (muscle is lengthening while working) and concentric (muscle is shortening while working) muscle work. Small, isolated muscle contractions tend to require concentric contractions and muscle tension (isometric work where the muscle contracts without any movement taking place).

Taking all of this into account, an average Barre class can resemble more of an average muscle strength and endurance workout than a ballet class, which is perhaps the safer option after all. At the same time, workout at the ballet barre can add variety and fun to the usual exercise routines. Learning dance technique, however, is a slow and detailed process that requires patience and consistency. In fitness classes, participants often want a continuous workout that they can immediately ‘feel’ in their muscles, not a focus on detail or engaging in a long learning process. Some Barre classes might have successfully married dance movement with exercise movement. This combination can result in ‘dancer’s poise’ and hopefully, also add some variety and fun to the variety of workout options currently available. Otherwise, one is simply ‘working out’ which can also be a great source of pleasure. Perhaps we should take note of my brother-in-law’s observation and suggest that upper body work, even for ballerinas, is needed for a balanced body. And what is wrong with doing any workout with some poise and elegance!

1.

Aalten, A. (1995). In the presence of the body: Theorizing training, injuries and pain in ballet. Dance Research Journal, 27(2), 55-72.

Dryburgh, A. & Fortin, S. (2010). Weighing in on surveillance: Perception of the impact of surveillance on female ballet dancers’ health. Research in Dance Education, 11(2), 95-108.

McEwen, K. & Young, K. (2011). Ballet andn pain: Reflection on a risk-dance culture. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 3(2), 152-173.

Solomon, R. Micheli, L. J., & Solomon, J. (1999). The ‘cost’ of injuries in a professional ballet company: A five year study. Medical Problems in Performing Arts, 10. 3-10.

Turner, B. S. & Wainright, S. P. (2003). Corps de Ballet: The case of the injured ballet dancer. Sociology of Health and Illness, 25(4), 269-288.

2.

Anshel, M. H. (2004). Sources of disordered eating patterns between ballet dancers and non-dancers. Journal of Sport Behavior, 27(2), 115-133.

Bettle, N., Bettle, O., Neumarker, U. & Neumarker, K. J. (2001). Body image and self-esteem in adolescent ballet dancers. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93, 297-309.

Ravaldi, C., Vannacci, A., Bolognesi, E., Mancini, S., Faravelli, C., & Ricca, V. (2006). Gender role, eating disorder symptoms, and body image concern in ballet dancers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(4), 529-535.

Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2001). A test of objectification theory in former dancers and non-dancers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 57-64.

3.

Banes, S. (1998). Dancing women: Female bodies on stage. London: Routledge.

Wulff, H. (1998). Ballet across the borders. New York: Berg.

Wolff, J. (1997). Reinstating corporeality: Feminism and body politics’, in J. C. Desmond (Ed.), Meaning in motion: New cultural studies in dance (pp. 81-100). Durham & London: Duke University Press.