Domestic Violence

New Findings on What Victims of Abuse Really Believe

The link between schemas and intimate partner violence.

Posted October 19, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Maladaptive schemas are distorted mental structures and patterns of experience (e.g., emotions, beliefs) concerning oneself and the world.

- Victims of intimate violence are more likely to have certain maladaptive schemas: Impaired autonomy, other-directedness, disconnection/rejection.

- Schema therapy may help modify maladaptive schemas and beliefs, potentially reducing intimate partner violence.

What do victims of abuse really believe about themselves and the world?

According to new research (by Pilkington and colleagues) published in the September/October 2021 issue of Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization correlate with several maladaptive schemas and core beliefs: impaired autonomy, other-directedness, and disconnection/rejection.

Before describing the research, let me define maladaptive schemas.

What are schemas (and maladaptive schemas)?

Schemas are mental structures. They help us anticipate and make sense of a lot of information quickly.

To illustrate, you probably have a schema about what will happen when you go to a coffee shop, bar, or post office. And what won’t happen. At the post office, for instance, you do not expect the postal clerk to offer you a glass of beer. If that were to occur, you would consider it abnormal.

Sometimes schemas themselves are abnormal or problematic. These erroneous mental structures and core beliefs are called maladaptive schemas.

Specifically, maladaptive schemas comprise dysfunctional patterns of perceptions, memories, emotions, thoughts, and sensations concerning oneself and the world. Maladaptive schemas develop during childhood and adolescence, often in response to unmet emotional needs, such as the need for acceptance, the need for autonomy, and the need to feel safe and secure.

Whereas adaptive schemas help us organize and interpret information quickly and accurately (so we can respond effectively), maladaptive schemas mislead us.

Maladaptive schemas might have been functional once, temporarily. For example, consider a little child who, after experiencing repeated abuse by his or her parents, forms the core belief that people are dangerous and untrustworthy. This is the child’s way of making sense of (and surviving) the abuse, and a way of preventing further mistreatment resulting from trusting others.

Of course, in an adult, the same distrust and paranoia—now in the form of rejecting all help or offers of friendship and romantic relationships—is more dysfunctional.

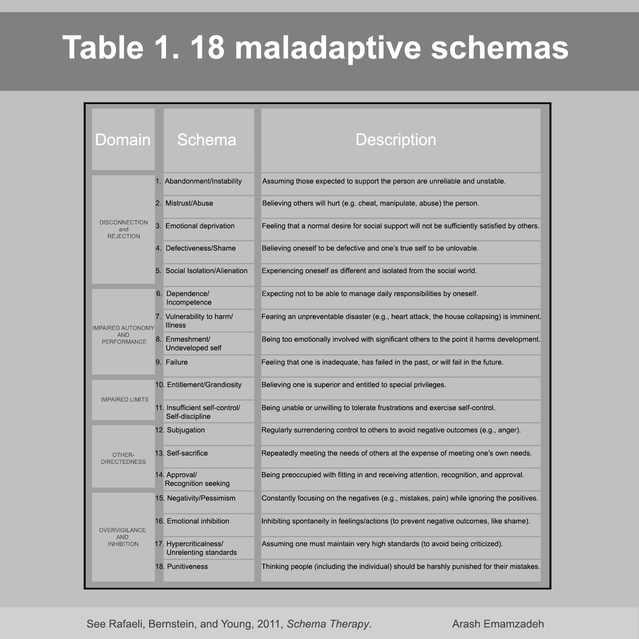

18 Maladaptive schemas

Eighteen maladaptive schemas, belonging to five domains, have been identified (see Table 1):

1. Impaired limits (two schemas): one, entitlement/grandiosity, and two, insufficient self-control/self-discipline. These patterns are more likely to develop in early family environments “characterized by permissiveness, overindulgence, lack of direction, or a sense of superiority.”

2. Other-directedness (three schemas): subjugation, self-sacrifice, and approval/recognition-seeking. Other-directedness schemas are associated with an early environment of “conditional acceptance,” and a constant need to “suppress important aspects of the self in order to gain love, attention, or approval.”

3. Impaired autonomy and performance (four schemas): dependence/incompetence, vulnerability to harm/illness, enmeshment/undeveloped self, and failure. This domain is associated with the violation of the need for competence and autonomy, leading to “expectations about oneself and the environment that interfere with one’s perceived ability to separate, survive, function independently, and perform successfully.”

4. Inhibition and overvigilance (four schemas): negativity/pessimism, punitiveness, emotional inhibition, and hypercriticalness/unrelenting standards. Often seen in early environments characterized as “grim, demanding, and sometimes punitive.”

5. Disconnection and rejection (five schemas): abandonment/instability, mistrust/abuse, emotional deprivation, defectiveness/shame, and social isolation/alienation. These schemas typically emerge when a child’s needs “for security, safety, stability, nurturance, empathy, sharing of feelings, acceptance, and respect” are violated.

An investigation of schemas and intimate partner violence

With the above information in mind, let us review the study by Pilkington et al., which examined the link between maladaptive schemas and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration.

Nine investigations were included in the meta-analysis. The total number of participants was 2,145 (80 to 435 per investigation). Six trials recruited women only, one recruited men only, and two recruited both genders. The average age ranged from 19 to 42 years. Designs were correlational (except for two case-control studies). Most trials were conducted in the US (others were conducted in Turkey, France, and Iran).

Results showed “small to medium pooled associations” between intimate partner violence victimization and the following schema domains: Impaired autonomy, other-directedness, and disconnection and rejection—the last one having the strongest correlation (r = 0.42, 95% CI [0.16, 0.62]). As for the schemas themselves, intimate partner victimization had a moderate correlation with mistrust/abuse and vulnerability to harm/illness schemas.

In terms of perpetration of intimate partner violence, the data was not sufficient for conducting a meta-analysis. Nevertheless, correlations were reported, in the studies examined, between violence perpetration and some maladaptive schemas. For instance, investigations by Hassija et al. and LaMotte et al. found small or medium correlations (r = 0.22 to 0.41) between violence perpetration and the mistrust/abuse schema.

What do victims of abuse really believe?

First, note that intimate partner violence victimization was most strongly correlated with maladaptive schemas in the domain of disconnection and rejection. This makes sense because many people who have experienced intimate partner violence do not feel safe, supported, accepted, or loved in their intimate relationships. They fear their romantic partner will manipulate or physically hurt them...or, eventually, abandon them.

Paradoxically, victims of abuse may also feel drawn to neglectful and abusive relationships—to unreliable, dishonest, manipulative, and cruel intimate partners. Why?

Perhaps because the behaviors of abusive romantic partners “validate” victims’ distorted worldviews—e.g., that relationships are dangerous and these individuals are vulnerable to mistreatment from abusive romantic partners or spouses.

Second, the data showed a correlation between victimization and the impaired autonomy domain. This may partly explain why many victims of abuse have trouble leaving abusive relationships: Victims lack confidence in their ability to function on their own or survive in a world they perceive as dangerous and unpredictable.

Third, the correlation between other-directedness and victimization indicates victims of intimate partner violence are commonly focused on the feelings, needs, and desires of others—likely motivated by the desire to gain their approval. However, other-directedness comes at the price of being unaware of own emotions and needs. Of course, even when aware, many abuse victims are afraid of being assertive and setting boundaries.

But there is hope for victims. Some evidence suggests schema therapy can be helpful in challenging and modifying maladaptive schemas.