Body Image

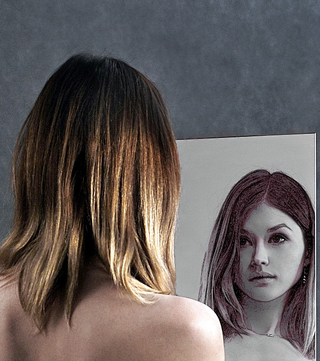

What Is Mirror Exposure Therapy? And Does It Work?

Mirror exposure therapy may be an effective treatment for negative body image.

Posted December 14, 2018 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

When looking in the mirror, some people see only wrinkles and bumps. They see fat in all the wrong places. Such a negative body image is sometimes associated with eating disorders or body dysmorphic disorder—characterized by preoccupation with imagined or slight physical defects. While healthy women spend roughly the same amount of time looking at their most and least attractive body parts, those with body dysmorphic disorder look mainly at the part they consider ugliest.

Negative body image is associated with low self-esteem, increased anxiety and depression, and abnormal eating patterns. A recent review article by Griffen and colleagues, published in the November issue of Clinical Psychology Review, has concluded that one effective therapy for those with body image distortions is mirror exposure therapy.1

What is mirror exposure therapy?

Mirror exposure therapy (ME) is a behavioral treatment used to treat body image disturbances in people with major concerns about their appearance or weight, or in those diagnosed with eating disorders.

In a typical ME session, the patient is asked to wear revealing clothes and observe her body in a mirror. Because of the requirement of revealing attire, a matching-gender therapist is sometimes preferred by women undergoing the treatment.

The specific instructions given depend on the type of mirror exposure therapy.

I review three versions of ME below.

1. Guided non-judgmental mirror exposure therapy

In this first variation of ME, the patient stands before a three-way full-length mirror and is asked to focus on—and describe—her body parts. She must do so using neutral and objective terms, as though she were trying to help someone build a model of her body.

For instance, the patient would describe her head’s texture, color, shape, etc, and then move to the next part—spending a similar amount of time on each area.

A description of the head and face is usually followed by those of lower parts (e.g., neck, shoulders, arms, breasts, stomach, legs, feet), concluding with a description of the whole body.

2. Pure mirror exposure therapy

In another variation of ME, called “pure mirror exposure therapy,” the participant focuses on her body in the mirror and comments on the emotions she experiences as she looks at her body.

In this and the previous version of ME, people can experience significant subjective discomfort. Nevertheless, the authors note that these two forms of ME are the “most effective forms of mirror exposure therapy tested” in those with eating disorders and body image disturbances.1

3. Mirror exposure with a positive focus

Some people cannot tolerate the distress and discomfort associated with the above types of ME. For them, a third variation is used, in which people are instructed to focus on their favorite body parts and to use positive language only.

For example, instead of talking about “problem areas,” one might say “I love my fingers. They are so long and beautiful. I love my face too, especially my skin. It is so healthy and smooth.”

How does mirror exposure therapy work?

Explanations for how mirror exposure therapy works include the following four hypotheses:

1. Modification of interpretation

People with eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorder have a tendency to interpret uncertain adverse situations by relating them to their weight or appearance concerns.

For instance, they might assume that they were rejected at a job interview or mistreated in a store because of how they look.

By facilitating a more objective and neutral view of one’s body, ME may reduce such interpretive biases. One might replace the thought “I know my classmates don’t want to go dancing with me because I’m fat” with “I don’t know why they can’t go dancing with me, but I can call them another time, or just call another friend tonight.”

2. Attentional modification

ME may reduce attentional bias and focus on particular problem areas—“bingo wings,” “double chin,” “saddlebag thighs,” etc.

Through cognitive retraining, ME could teach the individual to stop seeing her body through the filter of some “flawed” part; to encourage the person to spread her attention across her body, instead, and find a more balanced focus.

3. Exposure (as in exposure therapy)

Exposure therapy requires confronting the source of one’s fear (e.g., spiders). If we think of ME as exposure therapy, then the patient is asked to face fears surrounding her body image.

The assumption is that after observing the body repeatedly in an objective and focused manner, habituation takes place, so that one’s physical appearance no longer has the power to cause distress and anguish.

Another possibility is that ME creates cognitive dissonance, which then motivates change. Cognitive dissonance refers to discomfort associated with conflict between behaviors and/or beliefs that do not agree.

For example, a person who repeatedly describes her stomach as “white, somewhat rounded” is contradicting her negative beliefs—that her stomach is “too fat” or “disgusting and flabby.” While individuals in treatment might at first resolve this dissonance by doubting the truth of the neutral words they are speaking, they may eventually begin doubting their negative beliefs instead.

The effectiveness of mirror exposure therapy

Griffen et al. performed a literature search for clinical trials assessing the efficacy of mirror exposure therapy and found support for its effectiveness in healthy individuals and those with eating disorders. No study reviewed had examined ME in body dysmorphic disorder.

ME was shown to reduce distress, negative thoughts, and body dissatisfaction. In a few trials, ME even improved eating behavior.

Though mirror exposure therapy appears to be effective in some groups of patients (e.g. those with eating disorders), its efficacy remains to be proven in other groups—for instance, in individuals with clinical depression, those with a history of self-harm, people who are significantly obese or underweight, and men. That is why the paper’s authors urge caution in using mirror exposure therapy in these populations until further research is conducted.

References

1.Griffen, T. C., Naumann, E., & Hildebrandt, T. (2018). Mirror Exposure Therapy for Body Image Disturbances and Eating Disorders: A Review. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 163-174.