Anxiety

Postpartum Anxiety During a Pandemic

What works and what doesn't to manage anxiety—and a tool for sorting thoughts.

Posted April 5, 2020

My baby is napping, and I should be working or resting, but all I can do is read more news, check social media, repeat. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, confined to my home, all of my routines upturned, I am ravenous for some reassuring bit of information. It does not come, but I keep looking.

Things are likely to get much worse before they get better. Most of us are entangled in some version of panic, stress, and uncertainty from time to time. Like myself, many of us have become reassurance junkies in one form or another. We want to know the unknowable.

And if you have recently brought a new baby into your life, these feelings of uncertainty and deep anxiety (that most of the world are feeling) are likely deepened, compounded, and complicated by being in the tender and precarious postpartum period.

Postpartum anxiety can show up in the form of intense physical anxiety (e.g., increased heart rate, shortness of breath, dizziness, lack of appetite, GI issues, etc.), relentless worry and catastrophizing, intrusive and alarming thoughts, repeated checking (e.g., endless researching and asking others for reassurance), and overprotectiveness that results in not allowing anyone to help you with caretaking tasks.

In addition to anxiety, you may also be feeling a great deal of grief and loss for the way you envisioned this postpartum period going.

Add in sleep deprivation and hormonal shifts, take away normal healthy coping strategies and other sources of support, and this becomes a dark and scary place to be—more so if your mind is prone to anxiety.

Here are some general principles and a thought triage tool to offer some guidance for navigating the anxiety that may be hitting postpartum and is being ramped up by anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, it's important to understand what does and doesn't work to alleviate anxiety in the long term.

What Does Not Work to Reduce Anxiety

Attempting to control outcomes that are uncontrollable. When we are prone to anxiety, our instinct is to control as much as we can to make our lives predictable and safe. Oddly enough, babies do not always comply with our plans, and worldwide pandemics are hard to predict and influence.

Engaging in efforts to control outcomes we cannot control does not work to erase fear and doubt. Doing so actually tends to reinforce anxiety. It also has negative effects on our ability to be responsive and open in order to bond with our babies.

Trying to get reassurance and certainty (i.e., trying to know things that are unknowable). This can come in the form of researching, vigilant behaviors, asking others around you for reassurance, and ahem... frequent checking of news. It is impossible to get certainty for most of the concerns for which we are seeking it, and like trying to exercise control, seeking reassurance and certainty reinforces anxiety.

Being intolerant of anxiety itself and avoiding it. Anxiety (including physical anxiety symptoms and ongoing mental uncertainty) is unpleasant, but it is not actually dangerous. When we go to great lengths to avoid feeling our anxiety—even in ways that might seem healthy, e.g., deep breathing, etc.—the anxiety will keep coming back. It is not so much that these strategies are unhealthy, but the intention behind them, i.e., to make the anxiety go away, might be backfiring.

Taking every fear seriously, as if it is urgent. Just because we have a thought, and that thought is paired with an unpleasant, ominous feeling, does not mean there is a present threat that we need to attend to. Our minds churn out a lot of information. We do not need to take it all seriously or even pay attention to most of it just because it came to mind.

What Does Work to Reduce Anxiety's Impact on You?

Reducing resistance to and avoidance of anxiety. It seems paradoxical that letting yourself feel anxious would be a good thing, but it's actually the best thing. When we can engage in willingness to feel uncomfortable and uncertain, we can let an anxious fear pass through us instead of ensnarling us. This attitude shift is possibly the most powerful tool in lessening distress in the long run.

By practicing tolerating some feelings of discomfort and uncertainty, you give yourself chances to see that you can actually handle these feelings and that they pass more quickly when you are not resisting them, which gives you more confidence going into the next anxious moment when it comes up.

Connecting with the present moment. This means bringing your attention to what is happening right now without judging or evaluating the experience, but simply noticing and engaging in an intentional way. Practicing this skill creates opportunities to respond differently to your anxious mind.

When you are mindful in this way, you can use your breath and senses to ground you, catch your thoughts when they are wandering into the future (to feared outcomes that are not happening currently), and pivot your attention to something else that matters in the present.

Practicing an "and" mindset. We also all too often stop ourselves from doing things we might like to or from making room for other feelings, because we mistakenly believe we must be free of anxiety (or other unpleasant feelings) to do so. You can continue engaging in life and doing things that matter to you while feeling some anxiety: e.g., "I can be anxious and play with my baby," "I can be full of grief and still laugh with a friend on the phone," "I can feel unsettled and unsure and still take a nap or leave the baby with my partner."

Flexibility. Rigid thinking fuels anxiety and irritability. Notice how you feel and what you do when your expectations and your current reality are not aligning. These are often opportunities to ease up, soften to the present as it is, practice sitting with some discomfort, and challenge yourself to be flexible in your thinking and actions, moment to moment.

Labeling. Being able to decisively identify anxiety as such, rather than as an urgent call to action, can increase awareness and be a useful aid in clarifying how to respond. It can also be a great relief to be able to identify an unwanted thought as intrusive vs. worry.

It's a subtle distinction, but intrusive thoughts (a typical characteristic of obsessive-compulsive disorder) can be quite alarming and distressing to the person who is having them. These thoughts often involve doing something inappropriate or violent. They are not in line with your intentions: e.g., thinking of hurting your baby when you have no desire or intention to do so. There is less of a logical thread to reality. Worry, on the other hand, tends to be a process of imagining vivid and upsetting, often catastrophic, scenarios that might seem more reasonable or likely to happen.

It sounds simple, but just saying to yourself, "I am worrying right now" can clue you in to the fact that your mind is in the future, and there is nothing you can do right now to prevent the catastrophic situation you are imagining. Most importantly, it can remind you that you have the ability to bring your attention back to the present.

Humor and self-compassion. When we can get distance from our thoughts and not take every thought we have seriously or treat it as meaningful, we can observe our anxious minds at work with compassion and maybe even amusement. They are simply trying to keep us safe. Thanks, brains. You can also consider what you might say to a good friend or loved one in your position. You might be kind and encouraging, recognizing that they are doing the best they can and probably doing a decent job, given the circumstances. Tell yourself the same.

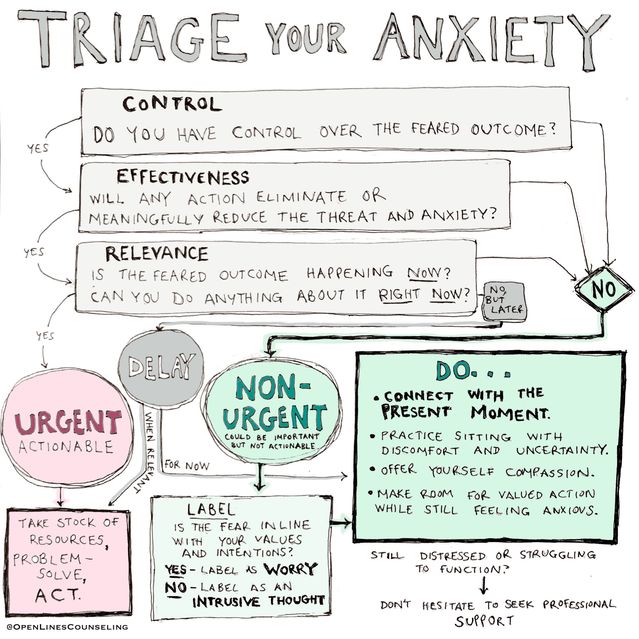

Triage Tool

Anxiety tends to create an unhelpful feeling of urgency, a sense that we must do something when there is often nothing to be done. It is worth gaining clarity on which thoughts are subject to productive problem-solving (especially in times when devastating outcomes may be more realistic than usual), and which should be lumped into the "anxiety" bucket so that you can then apply the cognitive and behavioral tools at your disposal.

Either way, you cannot tackle all of your fears at once. It's hard to function when you can't seem to catch your breath, when your anxiety feels overwhelming and unrelenting, like a gushing river instead of a manageable stream or trickle. Ideally, over time, you can learn to step out of the river completely, watching it and allowing it to flow without getting sucked into each particular thought and without it impacting your behavior or mood.

But for now and for particular thoughts that seem especially persistent, run them through these filter questions.

At the risk of using an inappropriate metaphor (but here I go), treat the worries as if they are patients in a waiting room. Take them one by one to determine which level of care and interventions they require.

Expect to feel anxious. The world is not likely to return to a state that we recognize for a long time. But know that you don't have to suffer. Don't dismiss your anxiety as "normal" if it is unrelentingly distressing, impacting your ability to function, or prohibiting you from embracing any moments of joy and connection with your baby, even if they are fleeting. Most therapists are now practicing teletherapy, and many are continuing to accept new clients. You can find trained maternal mental health professionals through Postpartum Support International's provider directory. Additionally, many support groups have moved online.

It is not fair. You did not ask for this. No one expects to have a new baby with the backdrop of a global pandemic. You are allowed to grieve the experience you imagined having in these months. It is more than understandable that your baseline anxiety level would be raised by the circumstances unfolding, the various areas of your life in which you have no control, and the lack of practical support and emotional connection.

You are getting a crash course in dealing with layers of stress, anxiety, and isolation that no new parent should have to deal with. Cry when you need to. Embrace each moment of anxiety as an opportunity to practice adopting a less-resistant and more compassionate relationship to yourself and to your anxiety. You are being given a chance to fortify your ability to respond to your anxious body and mind in a way that will serve you for years to come. Because even after the sheltering in place is over and we slowly and cautiously start leaving our homes and adjusting to a new normal, the parenting anxieties will not stop, only change.

And when the baby is napping, don't check the news.