Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Therapy

Could Accelerated TMS for Depression Become Standard?

Emerging treatment protocols offer guidance to safely expand TMS use.

Updated August 11, 2024 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation is safe and effective for depression and other conditions.

- We can expect ongoing developments as TMS research continues to evolve.

- Accelerated protocols work better in a shorter time, but are harder to perform and access.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) was first approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in 2008. Because it worked well for depression by using a strong magnetic field to stimulate key brain areas, TMS was recommended early on by the American Psychiatric Association in its 2010 Practice Guidelines (APA, 2010).

TMS has on-label FDA indications including major depressive disorder in teens 15-plus and adults, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), migraine headache, and smoking cessation. TMS holds promise for other conditions (Marder et al., 2022), and potentially for wellness-related applications1, all intriguing but requiring clinical caution, good evidence, and clear ethics with any off-label uses.

Accelerated TMS

Accelerated TMS protocols are of great interest, showing better results in a shorter time span than conventional four- to six-week courses, but aren't as well-understood or accessible due, as noted below, to technical requirements. A recent pilot study (Leuhr et al., 2024) looked at a series of 21 patients with severe treatment-resistant depression and treated them with a rapid TMS protocol, providing six to eight treatment sessions per day, each lasting only three and a half minutes, to deliver over 21,000 magnetic pulses in total. Importantly, no intensive techniques were required for localizing the treatment area. In this series of patients, 55% achieved a remission of depression within the initial week, and that number rose to 70%. Of those who did not fully remit, 55% experienced relief of at least half their symptoms. This is an open-label pilot study, and further research is required.

We were recently privileged to treat two patients (who provided consent to share their experience) suffering from chronic depression, suicidal thinking, and developmental and adult trauma and loss, receiving therapy and medications for many years with benefit but without full recovery, using this accelerated protocol. Both reported significant, and qualitatively remarkable, improvement by the beginning of the second day.

By the end of the week, they had achieved early resolution of almost all depression symptoms. While these results were in line with the pilot study, seeing it happen in real time was most remarkable. Close monitoring and ongoing psychotherapeutic support are needed to sustain and build on positive outcomes, and to determine if maintenance TMS is required.

Relief of depression lowers obstacles to growth and recovery but alone is often not sufficient. With a complicated developmental history, relational and life stressors, and years of living with depression, there is an important process of growth and recovery following successful treatment. For example, learning to differentiate normal strong reactions from depression, from post traumatic reactions, and from characterological issues are all important considerations once the underlying depression is alleviated.

What Is TMS?

TMS uses a strong electromagnetic field to directly stimulate the surface of the brain with fluctuating magnetic pulses2, causing neurons in that area to fire. TMS can either lead to longer-term activation, or suppression of activity in any given cortical region, depending on the type of stimulation used. The clinical effect depends on which areas of the brain are stimulated, and how they are connected with other brain areas. For example, the left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (L DLPFC) is typically treated for MDD, which in turn affects the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC), among other areas. By contrast, the left Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex (L DMPFC) is treated in some OCD protocols.

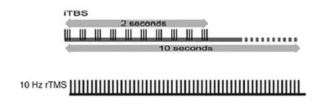

Traditional non-accelerated TMS protocols involve daily treatments, usually five days per week, for four to six weeks. Sessions are 30 to 40 minutes in length, and magnetic pulses are every 20-30 seconds with a 10 Hz (cycles per second) four-second long set of pulses. No sedation or anesthesia is required, or significant recovery time. This type of protocol works well, with remission rates over 60 percent, and corresponding high partial response rates. Over the years, it's been more easily covered by insurance, while accelerated protocols are less likely to be covered. Medication is not as effective on average3.

The effectiveness of TMS depends on many factors, including 1) the total number of pulses over the whole course of treatment and 2) how close together treatments are, one of the reasons accelerated works well. The pattern of magnetic pulses also makes a difference, for example using theta burst instead of standard 10 Hz pulse trains, as might how TMS is targeted4. Other factors are also important, including whether subtypes of depression respond better to different therapeutics.

Despite solid results, TMS has not captivated the public as have psychedelic treatments, including ketamine5. There is a natural tendency to compare TMS with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which may be a deterrent. ECT, unlike TMS, is not targeted, using direct electrical current to "reset" the brain by inducing a generalized seizure. ECT is highly effective—the gold standard around 80%—and well-tolerated, but requires sedation, anesthesia, and recovery.

SAINT TMS: Neuronavigated Accelerated TMS

In 2022, the FDA cleared SAINT (Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy™) TMS. This accelerated treatment uses brain imaging to identify which part of the L DLPFC has the weakest connection (the greatest anticorrelation) with the subgenual nucleus of the anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC)—shown to be a central node for treatment-refractory depression, though additional research from (Hopman et al. 2021) finds different network patterns than the area targeted in SAINT.

SAINT also uses iTBS, with remission rates close to 80%. Yet, SAINT TMS requires specialized brain imaging and additional medical equipment, offsetting the convenience of a week-long protocol. There is an ongoing debate among TMS researchers and clinicians as to whether neuronavigation is required, and if so for whom, and critically if we can obtain similar results with standard targeting6.

Future Directions

TMS is still in its infancy, and ongoing research is critical. Clinical depression is an urgent problem, affecting hundreds of millions of people around the globe, highlighting the need for better treatments. Notably, psychiatric medications are useful, but fail for many people especially as depression grinds on.

Psychotherapy is overall more effective than medication management (Shedler, 2010), and works best when part of integrated care alongside biological treatments. Therapy is often hindered by untreated depression, as well, preventing it from having a robust effect on personality and development when serving to support patients through difficult times. After TMS, it's key for people with more complicated problems to actively work to maintain and deepen gains.

Refining TMS protocols to allow for greater access and insurance coverage will allow more people to benefit, for depression as well as for other conditions. Accelerated TMS, without the need for brain imaging and neuronavigation, is an important development in lowering barriers to care. Ongoing research is necesssary to determine for whom simpler protocols are equivalent, and who requires more complex protocols.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

1. There is ongoing research to determine if TMS can be helpful for a range of conditions including ADHD, Bipolar Depression, chronic pain, psychotic disorders, sleep problems, anxiety disorders, PTSD, addictions, Alzheimer's Disorder and others. There is also interest in whether TMS can used for wellness and performance, given the potential capacity to improve cognitive function. Off-label uses of medications are common in medicine, and should be based in evidence and sound clinical decision-making. As with other medical treatments, it's important to use TMS appropriately and consent patients properly for treatment, given concern for inappropriate off-label advertising (Wexler et al., 2021).

2. The physics is important, as a changing magnetic field causes neurons in the brain to fire, or depolarize—following Faraday's Law. Michael Faraday was a physicist who discovered many of the basic laws of electromagnetism. The same principle is how electric motors work—if we pass electricity through a coil of wire, it produces a magnetic field, which can be used to make a shaft rotate. Standard TMS uses a figure-of-8 coil, and deep TMS an H-coil, producing a broader, less focused magnet field.

3. Medication is not as effective on average—per the STAR-D trial (Rush et al., 2006), the first medication tried has about a 30 percent remission rate, and additional medications are generally less and less effective with progressively burdensome side effects, making people more likely to stop treatments even when they are helping.

4. There is ongoing debate about how important precision of targeting is. For example, it may be that a narrow consistent target gets better results, while others argue that a broader, deeper field is more likely to stimulate key areas.

5. Ketamine, while not technically a psychedelic, is more widely available clinically than MDMA or psilocybin because it has been used for years as a dissociative anesthetic.

6. Standard DLPFC targeting involves either finding the treatment area in relation to part of the motor strip of the brain, an area above the ear which controls muscular movements, or using EEG (brainwave) coordinates using a technique called the "BEAM F3" method, based on mathematical calculations based on individual cranial measurements. Both have been shown to be fairly accurate, and identify a similar area for the majority of people.

Conflict of Interest Disclaimer: Dr. Brenner provides TMS therapy using the NeuroStar system - the device used in the Leuhr study reported on here - as part of his practice. He received no compensation from Neuronetics for this review.

American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2010: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

Marder et al., 2022: Psychiatric Applications of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

Wexler et al., 2021: Off-Label Promotion of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Provider Websites

Leuhr et al, 2024: Accelerated transcranial magnetic stimulation: A pilot study of safety and efficacy using a pragmatic protocol

Rush et al., 2006: A STAR*D Report

Kito et al., 2008: Changes in Regional Cerebral Blood Flow After Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Treatment-Resistant Depression

Hopman HJ et al. Personalized prediction of transcranial magnetic stimulation clinical response in patients with treatment-refractory depression using neuroimaging biomarkers and machine learning. Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 290, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032721004134.

Sanna et al., 2019: Intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation of the Prefrontal Cortex in Cocaine Use Disorder: A Pilot Study

Shedler (2010). The Efficacy of Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

An ExperiMentations Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Grant H. Brenner. All rights reserved.