Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

After the Shooting Stops: Civilian War Survivors and PTSD

New research on Balkan war survivors sheds light on the persistence of PTSD.

Posted March 9, 2022 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- The effects of war are visibile among civilian noncombatants long after peace is established.

- Once PTSD dysregulates brain systems, it can become a self-perpetuating problem.

- Physical problems, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbance are most closely associated with persistence of PTSD.

- Tending to such symptoms early may prevent persistence of PTSD.

As the war in Ukraine wages, and the world watches millions of refugees flee for their lives, we are reminded of countless prior wars. While media attention mobilizes our outrage and the outpouring of immediate help to affected civilian populations, what happens after the wars end?

We know that war takes a massive toll on the people, but our understanding of how the effects unfold for years after is still evolving. Do we forget to pay attention after the cameras stop rolling? What can we learn from past wars about post-traumatic stress?

PTSD Begets PTSD

Researchers Schlechter, Hellmann, McNally and Morina conducted a study of civilian survivors of 1990s Balkan wars, including those who had stayed in their countries of origin (including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia and Serbia) and those who had settled in Germany, Italy and the UK. The results wee recently published in the Journal of Traumatic Stress (2022).

Study authors focused on PTSD among war survivors to understand how symptoms emerge and change over time, and specifically how earlier symptoms predict and maintain later symptoms. Common symptoms of PTSD, including avoidance of trauma and emotional numbing, get in the way of people getting treatment, as do systemic issues like stigma and lack of resources, including paucity of qualified clinicians and lack of screening in at-risk groups in primary care settings.

Up to 227 million adult war survivors are estimated to have PTSD. A systemic review of PTSD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (2021) in countries affected by war in the last three decades suggests that 316 million people suffer from war-related PTSD and/or MDD. Half of the people in that study had both PTSD and depression, with about a quarter of people having one or the other, but not both.

PTSD can take on a life of its own, especially if left unchecked. Once trauma sets the brain off on a dysregulated pathway, it can become a self-regenerating system. Brain network activity is altered by trauma; for example, we may miss what’s right in front of us—problems in a relationship, a health issue—because we are so busy guarding against the return of past threats. Intrusive memories of past trauma may trigger further hyperactivation, leading to a cascade of symptoms.

Avoidance, akin to procrastination, may reduce short-term distress at the expense of preventing long-term restoration because we cannot become desensitized to traumatic memories. Understanding the specific pathways by which PTSD is sustained is key for successful intervention.

Survivors of War

Schlechter and colleagues recruited several hundred civilian war survivors to arrive at a final group of 698 participants, who were assessed for symptoms eight years post-war and then again one year later. Participants completed the Life Stressor Checklist-Revised to appraise stressful (potentially traumatic) experiences before, during and after conflict. PTSD was assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview and the Impact of Events Scale-Revised.

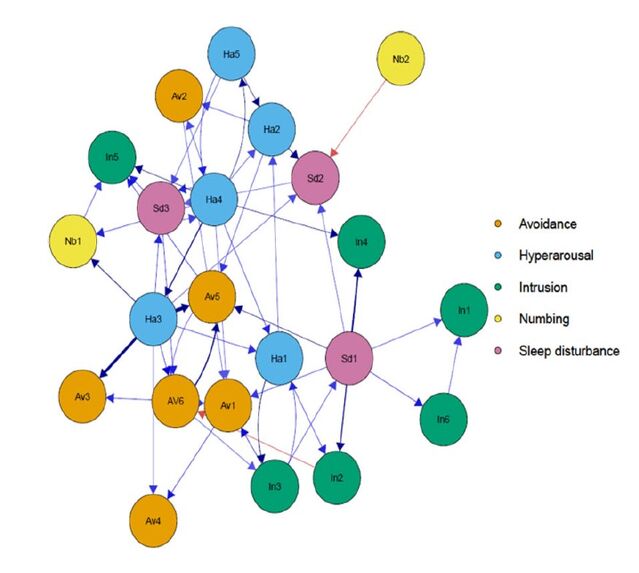

PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing/intrusion (memories, intrusive thoughts, nightmares), avoidance/emotional numbing, and hyperarousal (fear/panic, being easily startled, rage, etc.) were analyzed using network theory to determine first the correlations among symptoms at each time point and, second, the relationship between earlier and later symptoms, to show which symptoms in the present cause which future symptoms (causation).

The Anatomy of PTSD

Eight- and Nine-Year Time Points

Overall, there were moderate to high levels of trauma, with average IES-R PTSD scores of 2.45 at 8 years and 1.98 at 9 years (with 4 being most severe). The most frequent traumatic experiences reported were lack of food, lack of shelter, shelling, siege, and finding out a loved one had died violently.

At each time point (cross-sectional analysis)—eight years and nine years post-war—findings were similar for PTSD . The symptoms most strongly connected to PTSD were trouble staying asleep, trouble falling asleep, feeling as if trauma weren’t real or hadn’t happened, feeling numb emotionally, trying not to think about trauma, and trying to remove trauma from one’s memory.

There was a moderately strong correlation between thinking about trauma when one did not want to and avoiding getting upset if thinking about trauma (suppressing emotion).

Symptoms with the strongest impact (“expected influence centralities”) were having strong feelings about traumatic experiences, being jumpy and easily startled, and trying not to think about traumatic experiences. Network patterns were equivalent at eight and nine years post-war, but overall symptom severity decreased somewhat over time.

Which Symptoms Cause Future PTSD to Persist?

Looking at how earlier symptoms lead to later ones, network analysis (“cross-lagged panel network”) found five key relationships, in order of descending strength, as shown in the graph above by arrows connecting one symptom to the next. Thicker arrows indicate stronger causality:

- Difficulty concentrating led to trying to remove trauma from one’s memory.

- Difficulty concentrating led to trouble staying asleep.

- Trouble staying asleep led to pictures about trauma popping into one’s mind.

- Trying not to talk about trauma led to trying to remove trauma from memory.

- Reminders of trauma causing physical reactions led to difficulty concentrating.

The biggest predictors of future PTSD symptoms were:

- Getting physical reactions from traumatic reminders.

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Trouble staying asleep.

The symptoms most caused by prior symptoms were:

- Avoiding letting oneself get upset.

- Trying to remove trauma from memory.

- Acting like one was back at the time of the trauma.

- Dreaming about trauma.

Unpacking the Persistence of PTSD

Participants in this sample had a significant burden of post-traumatic symptoms, reflecting the findings from earlier studies on war trauma. Eight years later, they continued to report a high level of symptoms, which were lower the next year. It's tempting to wonder whether participation in the study itself had a therapeutic benefit, by combating avoidance and raising awareness of problematic symptoms.

Only 38.4 percent of the participants had received mental health services, and yet almost 90 percent had seen a primary care practitioner, highlighting the critical importance of screening in primary care settings.

Addressing the identified pain points may be useful in hastening the resolution of PTSD, a subject that future research can clarify. Reducing avoidance–gently increasing engagement with trauma–is important for treatment to be effective and key to recovery for many PTSD sufferers. Improving concentration may help improve sleep quality, which in turn could reduce the frequency with which traumatic memories spontaneously arise. Reducing traumatic memories reduces reminders of trauma, which would then be expected to reduce physical symptoms interfering with concentration. Body work can address physical symptoms of trauma, which increase traumatic reactions, and so on.

I Am Not My PTSD

Traumatic dynamics can end up taking over how our brains process information, experience, and relationships. Trauma can overshadow regular day-to-day experience long after the threat has passed, creating an all-present context that may be significantly disconnected from what is actually happening and leading to frequent distorted perceptions, misunderstanding, functional disturbances, and maladaptive coping.

In the extreme, PTSD may be mistaken for one's personality, especially with early or pervasive trauma, making it difficult for people to get in touch with their authentic sense of self and shaping life choices in regrettable ways. Recognizing PTSD and addressing key therapeutic levers is a potential game-changer: The often difficult work of recovery pays off with less future regret and greater self-regard, security, and life satisfaction. We have a clearer understanding of how war causes PTSD on a collective level, and left wondering how PTSD contributes to future outbreaks of war through triggering, avoidance and excessive aggressive reactions to perceived threat.

Graph Abbreviations

In1 = Any reminder brought back feelings about it; In2 = Other things kept making me think about it; In3 = I thought about it even when I didn’t mean to; In4 = Pictures about it popped into my mind; In5 = I found myself acting like I was back at that time; In6 = I had waves of strong feelings about it.

Av1 = Avoided letting myself get upset when I thought about; Av2 = I stayed away from reminders of it; Av3 = I tried not to think about it; Av4 = Lot of feelings about it; but didn’t deal with them; Av5 = I tried to remove it from my memory; Av6 = I tried not to talk about it.

Ha1 = I felt irritable and angry; Ha2 = I was jumpy and easily startled; Ha3 = I had trouble concentrating; Ha4 = Reminders of it caused me to have physical reactions; Ha5 = I felt watchful and on guard.

Nb1 = I felt as if it hadn’t happened or it wasn’t real; Nb2 = My feelings about it were kind of numb.

Sd1 = I had trouble staying asleep; Sd2 = I had trouble falling asleep; Sd3 = I had dreams about it

References

Hoppen TH, Priebe S, Vetter I, et al. Global burden of post- traumatic stress disorder and major depression in countries affected by war between 1989 and 2019: a systematic review and meta- analysis. BMJ Global Health 2021;6:e006303. doi:10.1136/ bmjgh-2021-006303

Schlechter, P., Hellmann, J. H., McNally, R. J., & Morina, N. (2022). The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in war survivors: Insights from cross-lagged panel network analyses. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22795

Note: An ExperiMentations Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Grant H. Brenner. All rights reserved.