Personality

The One Big Reason America Feels Disintegrated

Inherent fragmentation is coming to the surface now, and it's fierce.

Posted January 28, 2019

His life oscillates, as everyone's does, not merely between two poles, such as the body and the spirit, the saint and the sinner, but between thousands and thousands.

― Hermann Hesse, The Steppenwolf1

Contrary to common belief, our results reveal that cooperation can emerge among selfish individuals because of selfishness itself: if the final reward for being part of a society is sufficiently appealing, players spontaneously decide to cooperate.

― Bravetti & Padilla, An Optimal Strategy to Solve the Prisoner's Dilemma

In a little while

I'll be gone

The moment's already passed

Yeah it's gone

And I'm not here

This isn't happening

I'm not here

I'm not…― Thom Yorke, Radiohead, How to Disappear Completely

We enter 2019 as residents of a world full of constant changes, persistent annihilation-level threats, and exhaustive information overload. Our attempts to keep up — with an avalanche of tweets and social media posts, with news breaking by the hour, with a seemingly endless scroll of political scandals — are futile. And when we find ourselves unable to keep up, we tend to evade the challenges of the present moment by tuning out. This kind of dissociation is an understandable and yet dangerous coping mechanism. Readers should exercise caution and stop if necessary as dissociation- and trauma-oriented perspectives can be triggering.

Paying attention

When we are unable to attend to what is important, we give up the chance to understand what is going on in sufficient detail to develop plans and make good decisions. When we dissociate routinely, we lose inner cohesion, risking irreversible fragmentation. This is true on individual levels, but the stakes are much higher when an entire society is asleep at the wheel. Especially given the personality style of President Trump — which seems to shift, and swirl in chaotic patterns with sudden direction changes in motivation and self-presentation (yet remaining somehow very on-brand) — it is more important than ever that we make ourselves alert to exactly how this kind of individual and societal dissociation works and what we can do about it.

Today we are going to take a quick stroll through a complicated subject, dissociation and identity, and relate it to collective social systems using the analogy of a single yet balkanized personality to help provide a containing framework for understanding the diverse perspectives and multi-factioned struggles we are enduring in the current global climate. I am going to discuss the role dissociation plays in everyday life and in states of unwellness, explore the diagnostic construct of Dissociative Identity Disorder (formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder), survey the Structural Theory of Dissociation (a simple yet powerful conceptual tool we all need to know about), and finally draw parallels with our political and social systems.

Give us this day our daily dissociation

Dissociation in a modest degree is normal. We need to dissociate regularly in order to function, as occasionally tuning out the rest of the world is necessary to allow us to tune into the most salient and relevant information in our environment. We have to focus in this way — paying attention to one thing and not others — in order to drive a car for example. When we’re driving, it’s imperative that we shut out most of the rest of the world a bit and concentrate on the task at hand. We all have likely had a moment where we “snapped back” into it after letting our minds wander while driving (sometimes called "highway hypnosis" if profound enough), getting caught up thinking about an impending meeting at work or bills to pay at home.

We have to block much of that out in order to really focus on the many variables at present: the multiple and unpredictable cars around us, pedestrians and cyclists who may be sharing the road, uncertainty about directions in getting to an unfamiliar place, sudden obstacles in the road. Letting our minds wander too far back to our “real lives” for even a few seconds can not only be scary, but can be deadly — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 9 people are killed every day in the United States as a result of distracted driving. Dissociation, in this way, is a survival tool for a complex task. Even when we walk into a room, we generally don’t take in every detail of the scene. A single room could be overwhelming. Try to pay attention to everything happening now, every sensation of the body, every sensation from outside, thoughts, feelings, vague notions... as with mindfulness, when we let go of our filters and blinders, we start to notice so many things we never realized where there, and some of those things are really, really important.

Dissociation is also necessary when emotional pain is too high to tolerate, as when people experience abuse, terror, or other states of fear and helplessness. However, it’s important that dissociation be just a short-term coping tool, as in the long-run it can lead to big losses when we are absent during the present moment to avoid feelings and other experiences.

When important parts are “split off” — as when we need to go out of body during a horrible physical assault or when faced with overwhelming fears of total loss or failure — we also lose the functions associated with those parts. If aspects of childhood identity are hidden, we may save ourselves from fear at the expense of joy and childlike wonder. For example, someone growing up in a frightening and destructive house may learn to suppress playfulness and curiosity in order to remain vigilant, or meet caregivers’ unhealthy demands, learning to restrict and constrain their personality and expressiveness in order to avoid mistreatment.

Dissociation is a defense especially important for children, who haven’t yet developed a full sense of self or more adaptive adult coping strategies than simply closing the blast doors — though reliance on dissociation can persist, under certain circumstances, into adulthood. It is a last-ditch survival move, the psychic equivalent to when a lizard drops its tail as concession to a pursuing predator in order to escape. For lizards, the tail naturally grows back and the predator gets a tasty lizard-tail snack. For people, the lost parts of the self may return or resume development and "grow back"... they aren't typically consumed but may remain underdeveloped while dissociated... and it is more difficult than a lizard's regeneration. It requires a healing, safe and trustful set of circumstances, especially when trauma involved intimate others. When an unsafe world led to fragmentation for the sake of survival, finding a safe-enough world is required to begin to thrive.

Because dissociation is considered developmentally to be one of the earliest defenses human beings use, I tie dissociation in with human nature, one of the basic frameworks required for maintaining a sense of personal identity and shared social reality. Psychologically, we distort understanding, self-perception, social impressions, and so on, in order to keep things moving along. Sometimes this is done through inadvertent, unconscious bias, while at other times, it is enacted through motivated self-deception and willful misdirection of others.

We are experts at theater and conceit; at our best, we learn via play rather than trial and error. In large part, our world is built on smoke and mirrors, as much as it is built on nuts and bolts. We are intelligent creatures, capable of imagination, and more to the point, simulation. This allows us to fantasize about things which could exist, and bring them into being, blurring the line between fantasy and reality. For example, science fiction often predicts technology which becomes real decades later, as what once seemed like a pipe dream becomes feasible with advances in science. Fantasy and reality are often the same; it's just a matter of time.

Moreover, we are at cusp of an evolutionary singularity as highlighted by the viral 10 Year Challenge, confronted with stark choices about how to survive and adapt as a consequence the very circumstances we have created, and are sustaining. The catalysts of our civilization’s exponential growth are efficient interconnection, faster and faster communication, unprecedented powers and potential, and the population explosion, which ensures an expanding cadre of geniuses, if only as a matter of statistical inevitability.

How is the social world made?

We are producing this world together more or less automatically, with no collective conscious will and no coherent leadership. We really can live together in our utterly different subjective realities, as long as we behave in ways which co-sustain our shared reality. There must be sufficient overlap, and we do have more in common than differences. Yet when things go sideways, we are caught off guard, get caught up in urgency, group think and threat-response, and easily make wrong decisions.

It takes tremendous effort to stick with rational plans for dealing with things handily, a major force of will to pause and reflect reflexively, a skill acquired through repetition until contingency plans are ingrained and habitual. Understanding why it is so difficult to switch gears when the situation demands it, requires understanding how the mind works so that we can make sense of seemingly irrational responses: fragmentation, self-destructive actions when a healthy path seems obvious, sudden discontinuous jumps in behavior, feeling and thinking, and related “nonlinear” effects which are more the rule than the exception in human individual and social experiences. We like to see ourselves and our social systems as smooth and continuous, and try to set them up to be this way, but in reality we are simply more messy than otherwise. And we want to hide the messiness to maintain the illusion of continuity, a useful but at times fragile safety net.

The Structural Theory of Dissociation and Dissociative Identity Disorder

A condition of great fascination and much misunderstanding in popular culture (unfortunately, for those who live with it), Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is thought to a significant degree to the be result of severe early trauma. Contributing factors include emotional, physical and sexual abuse, as well as neglect and chronic gas-lighting by caregivers who are unable to provide a basic developmental environment. These factors, when combined with a proclivity for dissociation, can lead to a profound disruption of sense of self, resulting in the aforementioned “multiple personalities.”

The catch is that those with DID do not actually have many different personalities. Instead, they have subsystems of personality which are not integrated with one another. These subsystems represent different aspects of the more coherent and cohesive personality which would exist in the presence of a more healthy developmental experience. The different sub-systems tend to form pairs and sub-groups which represent different aspects of and responses to trauma.

Some people appear to be more prone to dissociation than others, with a greater facility for fluidity of identity, often a highly adaptive social trait. In absence of trauma, such folk may be more capable of taking on multiple perspectives, seeing things from many different angles, an inherently healthy way to be in the world characterized by less conflict when different perspectives are in communication and can co-exist well. They may be able to move from role to role, or occupy a role so completely as to seem like the original, even hyper-authentic and more original than the original itself. Think about actors who can seem to become another person as part of their craft or politicians who are able to wear many faces with ease. To an extent, the ability to pivot, to take on the right persona for the right situation is very adaptive. But when it leads to hiding things from oneself, we end up tripping ourselves up, leading to scandals, grievous errors in judgment, and bad decisions we don’t even know why we made.

Singularity

What may appear to be falseness, hypocrisy, inconsistency, thoughtlessness, or manipulation may be the result of a lack of integration, and not willful action or true motive. It is often helpful when dealing with others (and oneself) to get a sense of how “singular” their personality is, as contrasted with their degree of multiplicity, as a normal trait, in understanding motivation and behavior. You can see this in how consistently a person actually behaves, from situation to situation, and from person to person. Some people can change drastically depending on the circumstances, masterfully adapting with a chameleon-like facility, while others are more similar regardless of what’s going on. Some folks can hold multiple perspectives, tend to be higher in compassionate empathy, and often serve as a translator among different factions and facilitator of integrated change (as contrasted with unilateral aggressors who can bring about change through upheaval).

We often experience ourselves as single-minded when in fact we have disparate and sometimes conflicting views and desires. Rather than experiencing cognitive dissonance, however, we may suppress our awareness of self-discontinuity, acting as if everything made sense. We may edit thoughts, feelings and memories after-the-fact to maintain a consistent sense of self. Memory is highly malleable and unreliable according to a growing body of research, yet many still believe that if they are sure something happened the way they think it happened, it must be true. This is a form of emotional reasoning. It feels true, so it must actually be true. What does it mean for something something to feel true? What is the feeling of unassailable logic?

For example, I may convince myself that I discussed and agreed on a specific action plan with my partner, and that’s what I remember (and often get into conflict over), when in fact I never made a clear decision at the time, or selectively remember the parts of what I said which support my current frame of mind. Memory is known to be "context-dependent", making it difficulty to get the whole story. In my memory, I may recall a circumscribed, distorted sense of what happened, the one which fits with my sense of who I am at that moment e.g. someone who is clear and decisive, and never in error. It's often against an external other that we fall into this trap, though we can be so divided against and within ourselves, while remaining unblissfully unaware of the inner discord, perhaps ascribing the anxiety to someone or something else.

Dissociative identities

According to the DSM 5 — the psychiatric diagnostic manual published by the American Psychiatric Association which is used for treating mental illness — in order to meet criteria for Dissociative Identity Disorder, a person must have at least two distinct personality states — if not more — and each personality state must have its own “relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to and thinking about the environment and the self.”

The personality states must be cut off from one another, involving “marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency,” with symptoms in many other areas involving thinking, emotion and behavior. Notably, those with DID may experience possession, as in having one’s mind and body taken over by a malevolent supernatural spirit with malicious intent.Another hallmark of DID is loss of memory for important events and actions. With this kind of amnesia,hose with DID forget not only traumatic events, but also ordinary, non-traumatic events. memory is “state-dependent,” meaning that what happens in one emotional state or one context may not carry over later.

The last three criteria for DID are common to all psychiatric disorders, requiring that the symptoms cause significant distress and/or dysfunction, and aren’t better accounted for by another condition, such as another psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, general medical disorder, or rare cases of malingering or factitious disorder.

Before being diagnosed with DID, those with DID are often diagnosed with other conditions, including depression, anxiety, personality disorders and substance use problems, among others. Those with DID are often unaware when their personality states shift. For example, they may go from being very kind and cooperative to hostile and mistrustful, unaware that anything has changed, while others around them experience them as being completely different. When confronted, a common response would be to attribute the problem to the other person, accuse them or think they are incompetent, which would seem like the only sensible explanation without being able to see problems in one’s own behavior. They may spend time with people who know more about them than they know about themselves, as they may communicate important yet consciously forgotten information while in a dissociative state.

Dissociation blocks developmental integration

Because of the behavioral inconsistency resulting from shifting between personality states and inability to provide a sensible explanation or even discuss the possibilities in a civil, rational way, people with DID are often accused of lying and manipulation. Yet they are typically not ill-intentioned. But without knowing the full story, it makes the most sense if that's what you expect from people especially — or the easiest sense, really — to think they are lying, faking or being otherwise manipulative in some way, leading to recurrent snowballing problems with relationships, work and family. Projection is a powerful defense, making each unreal to the other. When parts of ourselves are offline, resilience suffers. Integration among parts, self-synergy, is crucial to being complexly adaptive.

Guardedly optimistic

People with DID do benefit from treatment. Effective treatment should result in greater awareness of internal states and their relations with one another and greater internal cooperation. Ultimately, the goal is that those disparate sub-systems join — perhaps in varying degrees — into a more integrated sense of self. This involves overcoming a variety of inner barriers, fears of exploring one’s inner world and fears of the outer world and other people, from early developmental experiences to more sophisticated complexes, starting with fears about what is going on within one’s own mind, fears of danger from other people, and issues with self-care, moving through phobias of traumatic memories, and on to the fears and anxieties which come up every day.

The apparently normal and emotional part(s) of the personality

The structural theory of dissociation2 is a road map for gauging the severity of dissociation. It describes three levels of dissociation depending on the extent to which fragmentation affects the self present to the world, one another, and ourselves as “normal” — called the ANP, or the “apparently normal part” (or parts) of the personality — and our emotional self-states — the EP or “emotional part(s)” of the personality — which we often hide and have difficulty regulating because we are not in communication, let alone control.

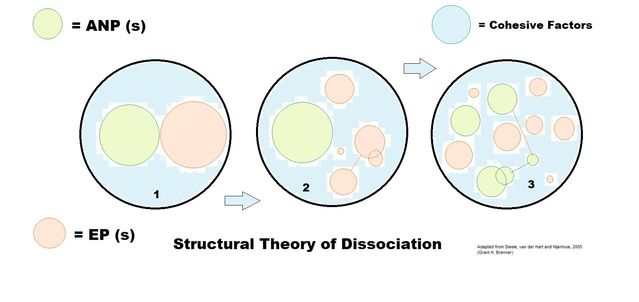

The first level of structural dissociation, Primary, involves a basic split between the ANP and EP. This means that feelings are split off from our day-to-day presentation, inaccessible to ourselves unless they get intense enough to break through significant suppression and numbing. In the second level of structural dissociation, Secondary structural dissociation, the ANP remains intact, but the EP is fragmented, to varying degrees of severity. The parts of the EP follow brain-based motivation systems, breaking down emotions into more and more separate buckets as dissociation increases. As dissociation becomes more profound, different fragments of EP may capture specific emotional states and meanings — specific phobias, aggression and rage, a desire to flee, a desire to fight back, intense pleasure with a specific activity, and so on. This is more confusing and problematic as one tries to maintain a singular consistent ANP both personally and socially. At the third level of dissociation (Tertiary, which lines up with DID), both the ANP and the EP are fragmented into multiple self-states, resulting in a kaleidoscope of identity. Within each level there are differences in severity, with greater or lesser fragmentation. There are also differences in the specific "architecture" of each personality, a function of different innate and social-environmental developmental influences, as is the case with people in general. You can map it out, lines between circles representing locally connected clusters:

E pluribus unum

The US political system meets the main criteria for Dissociative Identity Disorder, if we pretend for a moment our country is a person. First, with its multiple political parties — primarily the forever feuding Democrats and Republicans — it has two or more personality states which are largely independent of each other and have unique ways of relating to and perceiving both the larger environment and themselves. There's more subdivisions, discussed in detail below, but these in some sense are primordial. Until recently, for example when we are starting to see loosening of the rigidly dissociative quality, the political groups vote in blocks along party lines. Secondly, we see severe disturbances of memory with frequent lapses and distortions of memory which maintain continuity and avoid recognition of discontinuity. Stories change as the situation demands, seemingly without recognition that there are inconsistencies and contradictions.

America was born from collective trauma, on many levels. Religious freedom, exploration, exploitation, slavery, genocide, emancipation, conflict, Civil War, racism, gender and class bias, and a Constitutional structure ensuring permanent divisions without guaranteeing full communication or cooperation. This is both a strength and a flaw, but as the old saying goes, it's the best we've got. Especially when the alternative was being ruled from afar by unilaterally dominant autocratic nation. Ironic, perhaps, now when American is viewed with mistrust by less powerful nations for reportedly similar reasons, accused of being cloaked within our idealism and blind to our true nature.

Various legal and bureaucratic systems, check and balances, and informal lines of authority serve to create a container for what happens in our political system, but it is more or less a dynamic, self-organizing system with multiple, independent centers of control which are partially linked with one another, but to a significant extent are both independent and unaware of much of one another’s actions and thoughts. In fact, they must be unaware in order to function properly, to avoid accrual and abuse of power through monopoly.

It is the President's job to uphold this structure, not violate it. Likewise, you have a right to keep your vote secret, though you are free to speak it, to make sure no one has too much power. If you go around telling people you didn't vote, though, you are likely to upset them. Arguing that voting doesn't make a difference is a dead-end debate. Checks on power, and secrecy, also make it harder to work effectively together especially when conflict is high and forecloses on compromise. It's supposed to involve health debate and consensus, but that hasn't happened in a long time here. When both parties fall into groupthink around charactured ideologies, cross-pollination between parties becomes scarce to an unhealthy extent. That's not what the Founding Fathers intended.

Pick a side

There is a deep symmetry here in the two party system: liberals can easily see the inconsistencies and “lies” of the right but not their own, and conservatives can point out how liberals don’t make sense. They share in common an inability to self-reflect candidly, along with the tendency to assume that each has the higher moral ground. In such a fragmented system, efforts to communicate turn instantly into heinous attacks. There is no middle ground, no sense of sanity in these relationships.

There are problems with identity on the level of political parties, with both major US parties facing identity crisis. The Republican president, for example, has not been a Republican long and yet has taken possession of the Republican party with little resistance. He seems in so many ways a study in mutually incompatible opposites. People who don't seem like the should, or should be able to, identify with him and want him to win do identify with him, and see him as a force for good: a rich man who is revered by the working class, a grabbing misogynist who is supported by many women, an alleged racist who is adored by more black Americans in seeming defiance of the imagination.

The Democrats went through a different yet parallel morphing of identity, expressing one aspect of treasured American ideals of immigrant opportunity and progressive values, in having first a mixed-ethnicity president, and then a battle between a woman and a Jewish man for the nomination. In the end, the 2016 election pitted the perceived charade-you-better-take-seriously of a Republican white male against an establishment-favorite woman Democrat. Universal split appeal to progressive and conservative tendencies simultaneously. Ultimately regressive in the psychological sense of returning to a more primal rate, so full of hatred and repellent ideas, and tragically dashed hope.

To date, there's arguably a lack-luster sense of identity and purpose among the Dems, and in the recently mid-term elections we are starting to see more radicalized post-Trumpian individuals filling in the dissociative splits which are becoming more and more evident. Rifts within the party can blow things to pieces, but also create an impetus to adapt and evolve, making room for the emergence of new forms. Ocasio-Cortez is a good example of this shift, a kind of mirror universe Trump, similar with regard to bluster and an apparent shamelessness, which nevertheless is very appealing and liberating for so many. Newly empowered Democrats appear to borrow from Trump’s playbook, as old inviolable rules become suddenly insubstantial. Walls become diaphanous veils, and borders become walls.

Confuser-in-Chief?

The Trump Administration itself has features suggestive of dissociative processes. First, there is distortion and denial of reality, which is replaced with fantasy and projection. Obama is not American. The crowd at my inauguration dwarfed his. ISIS has been defeated and so we can leave Syria. This may not be mere narcissistic self-delusion writ large; it may be signs of deeper disorganization. Second, there is a loss of internal structure, as we can see with an unending stream of firing and resignation in the cabinet and administration. In fact, the structure itself seems to be constant turnover, or churn, around a central axis. A political vortex.

Parts of the system which do not fit with the dominant identity are split off and ejected. Yet, they remain part of the system, in orbit around the center with the aid social media. We see this with James Comey via social media and his book, Preet Bhahara with social media and his podcast, and Mattis and Tillerson, among others, are making their voices heard through the media even after their formal departure from the administration. They get stronger, in a way, freer to act once let go. They are still in relation to Trump, though the relation is transformed. Many personalities in irrelationship with one another.

We see a lot of two-faced behavior as part of this, almost in the same breath — proclamations of friendship and unity followed by declarations of disdain and repugnance. There’s a never-ending stream of alleged betrayals and firings, a near-constant turn over of high-level staff, sudden reversals of fortune connected with sudden changes in favor and disfavor which goes beyond mere narcissistic responses to injury to severe splitting and fragmentation.

The breakdown

Our political system is at the highest apparent level of identity, binary. Where is the one, from many? It is just an idea, but a powerful one, religiously-ordained in one nation under God, in spite of separation of Church and State. The nation is split in terms of culture and values, pro-life and pro-choice, socialist and capitalist, freedom and slavery, justice and injustice, rebellion and conformity, uniqueness and blandness, freedom of speech and political correct hushing, and the list goes on and on. I believe it is part of the DNA of our nation more than any other, because of how we started and what was set up by the Founding Fathers.

Given the inherently constrictive binary dynamics of over-rigid conflict, the development of third alternatives is challenging. For example where do fluid definitions of gender and social identity fit in? How is it that I can be friends with people who disagree with my political positions and support someone I may loathe, while we also share so much in common, and are totally sympatico about many things? And how is it that I can also disown close friends and family members because of their vitriol and utter violent rejection of what I hold dear?

A way to harness complexity?

When things don't make sense like this, I look for structural dissociation. I believe we are in the midst of a re-organization, and what happens in the next 10 years, or sooner, is going to determine the next several decades at least, and may portend an existential crisis beyond what we've ever seen. Our nation, and the world by extension, has been thrown into supersaturated, hypercritical state, where relatively tiny moves can be unpredictably amplified and big pushes do little, if anything. The external blow of 9/11 introduced a crack, and the election of Obama and now Trump is driving a wedge into that fissure creating a passage for things to come out from within, and move within from without, generally creating turbulent eddies and whorls, departures from the familiar, predictable dynamics of not so long ago. We are undergoing a phase change, as when water begins to boil and turn to steam, liquid turns to gas.

Having enemies works for a time, it's a temporarily stable solution, but ultimately reflects unconstructive dynamics and is not a long-term survival strategy. Since we are stuck together on this shrinking planet, we face an increasingly pressured prisoner's dilemma, caught between the need to cooperate and the impulse to defect, and turn against one another. If we are selfish and recognize our interdependence, we should end up getting along. Hopefully trying to get along won't be what does us in.

What we do now is of the utmost importance, and being informed of the dissociative nature of our system may enable us to see beyond hidden, short-sighted and often destructive dynamics which dictate our decisions, undermine compassion and empathy, and make us appear as enemies to one another. Are we approaching a point of no return? We are massively interdependent and don't quite understand what that means, roped-in together so that if one person falls, the resilience of the whole system will be tested. This is the perfect time to slow down and think more reflectively, while remaining alert.

1. from The Steppenwolf: “The mistaken and unhappy notion that a man is an enduring unity is known to you. It is also known to you that a man consists of a multitude of souls, of numerous selves. The separation of the unity of the personality into these numerous pieces passes for madness. Science has invented the name schizomania for it. Science is in this so far right as no multiplicity maybe dealt with unless there be a series, a certain order and grouping. It is wrong insofar as it holds that one only and binding lifelong order is possible for the multiplicity of subordinate selves. This error of science has many unpleasant consequences, and the single advantage of simplifying the work of the state-appointed pastors and masters and saving them the labors of original thought. In consequence of this error many persons pass for normal, and indeed for highly valuable members of society, who are incurably mad; and many, on the other hand, are looked upon as mad who are geniuses...This is the art of life. You may yourself as an artist develop the game of your life and lend it animation. You may complicate and enrich it as you please. It lies in your hands. Just as madness, in a higher sense, is the beginning of all wisdom, so is schizomania the beginning of all art and all fantasy.”

2. Developed by Pierre Janet, the pioneering French psychologist who coined the term “dissociation”.