Health

A Psychologist Revisits the Tragedy and Humanity of 9/11

My firsthand account from Ground Zero.

Posted September 11, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- My disaster mental health responder's role was to support first responders—police, firefighters, and handlers of cadaver-sniffing dogs.

- I listened to stories and recollections of gruesome events, and assessed for anxiety, depression, and other emotion.

- The outpouring of caring for others was evident everywhere.

I left northern California for New York City, my birthplace, as soon as I could get my Red Cross Disaster Mental Health volunteer documents in order, just two weeks after the attack in lower Manhattan. As a psychologist, I already had the training and just needed a hard hat, badge, and walkie-talkie, and a flight to get me there. My role was to support the efforts of first responders—police, firefighters, handlers of survivor- and cadaver-sniffing dogs, and volunteer medical personnel as they struggled to manage the horrors.

Wearing a helmet, goggles, and face mask I left my emergency response vehicle and entered a surreal space, once the World Trade Center, noting a smell permeating the air that defied description. Some said it smelled like death or maybe the electrical smell of a melted toaster cord. Hot smoldering hills of rubble rose from the ground and manholes.

The smoke was so heavy at the makeshift police station at Ground Zero that walking the flight of stairs took enormous effort. The whole scene was eerie and seemed like a black-and-white movie in slow motion. Delivering food and drink to disaster workers there, I noticed how little they talked, communicating through eyes that were sad and intense. The mood was somber, resolved, and very subdued. New York was humbled by Sept. 11 and you could see it reflected in locals’ behavior—less horn honking, more courteous encounters, and recognition of sorrow in each other's faces. It was business as usual but with a tenderness I’d never before witnessed in New York City.

Winding my way up to the top of the landfill at the Staten Island facility designated to sort body parts, I could see at a glance that this was no ordinary place. Enormous hills of mangled metal dotted the landscape. I knew what was in the piles and why there were people raking the ground and why others were watching debris pass over a conveyer belt. The mission of this place was awesome: trying to separate building materials from human remains.

Even though I was acquainted with the facts, I wasn’t prepared for the mood of this place— melancholy, quiet, and, for a New York setting, uncharacteristically gentle. On a walk through the mess hall where hundreds of exhausted disaster workers ate around the clock, I observed a sense of seriousness and comradery. Outside it was very cold; the early November wind was howling and it was hard to keep the swirling dust and debris out of my eyes. I used my gut to pick out workers whom I thought might benefit from some conversation or support and took my lunch with them.

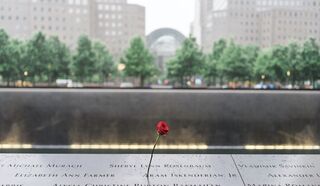

The slow, painstaking work was critical because the facility served both as a crime scene and a personal memorial. The losses were very real to the locals, many of whom have lost someone or had a friend who did. This was sacred work, made clear by the clergy of different religions who blessed the ground where bodies had been brought, but of course couldn’t be definitively identified. I thought that the whole landfill ought to be regarded as a sacred burial ground or identified as a memorial site—the final resting place for so many people. I hoped that this would mark the end of a tragedy and a step toward recovery.

As if the mood in New York weren’t somber enough, the crash of a commercial plane in Rockaway Beach on Nov. 12 ratcheted up the general nervousness several notches. The site was less than a quarter-mile from where I was stationed and I saw the plumes of black smoke as I was riding in a Red Cross Emergency Response vehicle on my trek to provide food and water to disaster workers at Ground Zero.

My new orders rerouted me to Rockaway Beach to talk with local residents who were traumatized by the crash, either from seeing the crash itself or the destruction of homes, their own or their neighbors. I saw disbelief, anger, and fear on their faces as they assembled at the barriers constructed at the crash site. A temporary morgue was set up within their view. They came alone or in families. Kids in twos and threes wandered by to gawk, cry, and inquire about the safety of their neighbors.

A woman rocked as she sat on her porch steps facing the burned-out remains of the house across the street. Another woman sat in shock. Her house was demolished with a piece of the plane sitting in what had been her front yard. Even though all of the tangible reminders of her former life were taken by the fire, she was focused on a mother and child, neighbors across the street, who had perished in the fire. She was also reliving an earlier loss, the death of her husband, who was a police officer killed in the line of duty nine years ago. The earlier horrible events on Sept. 11 were recalled with renewed intensity and superimposed on the current loss. Over and over I saw people being re-traumatized, this crash being just the latest assault on their lives. Rockaway lost 84 people at the World Trade Center. Now this. It was almost unbearable.

The owner of the Harbour Light, a bar-and-grill on the corner near the crash, lost his son on Sept. 11 at the World Trade Center. He opened his place to all disaster workers to use the facilities and relax. His kitchen made a huge submarine sandwich for me to take to a woman who lost her child—no charge. The outpouring of caring for others was evident everywhere which was heart-warming in this community already in mourning. As I witnessed the drama unfolding I remembered that in spite of New Yorkers’ usually rough and seemingly detached style, there is also passion and compassion that surface when times get tough.

I often hear the question, what exactly does a psychologist with disaster mental health training do in situations like this? Since my role was to support first responders and others who witnessed horrors, my job was to listen and assess. Listen to stories and recollections of gruesome events, listen for anxiety, depression, and other emotions that psychologists are trained to support. First responders are, after all, human and have the same emotional experiences and responses as the rest of us. They are often less willing to share these, but my being there at the right place and right time, sharing many of their experiences, made it somewhat easier for them to express, grieve, and thus heal. Secondarily, I assessed whether a situation or experience threatened a person’s ability to function—which I saw more with bystanders, with whom I would follow up with recommendations for local ongoing support.

After daily shifts that woke me at 4:30 am and didn’t end until nightfall, sleep didn’t come easily. But writing did. This immersion proved invaluable. Keeping my sanity meant chronicling what I witnessed and observed on a daily basis because some of it was so unspeakable that talking to loved ones at home wasn’t an option. In looking back, I was amazed at the resilience of Americans to deal with disaster and come together with heroism and compassion even in the darkest of times. Three weeks later I returned to California. Ten years later I was diagnosed with lung cancer like so many disaster responders.

At the time it seemed impossible to imagine that an attack on American soil would ever be repeated. Yet here we are two decades later following a domestic attack and ongoing threats from foreign adversaries. Domestic terrorism is something new, but our ability to come together as a nation of patriots is not.