Parenting

The Biggest Problem With Parenting Advice

Following parenting advice may throw you out of balance.

Posted December 3, 2014

The biggest problem I see with parenting advice is that it inevitably tends in one of two directions. Either it pushes you toward a sense of control, offering you tools to engineer impossibly specific outcomes, or it urges you to relinquish control categorically (Stop micromanaging! Get out of your kids way!).

This tension has defined the history of child rearing advice. In the 1920s and 1930s, when the American parenting advice industry began, authoritarian parenting rooted in behaviorism was in vogue. According to this theory, children were expected to do as they were told or else be punished. A child reared without strict rewards and punishments, it was thought, would become out of control. Experts warned that even holding a crying baby would reinforce the crying behavior (Sterns, 2004).

Based on the theory that a mother’s smothering love could retard a child’s development, one behaviorist advised:

Never hug and kiss [children], never let them sit in your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say good night. Shake hands with them in the morning… Try it out. In a week’s time you will find how easy it is to be perfectly objective with your child and at the same time kind. You will be utterly ashamed of the mawkish, sentimental way you have been handling it (Watson, 1928, 81-82).

In the 1940s, because of the work of John Bowlby, affectionate attachment returned, with advocates citing cases of maternal deprivation in orphanages where infants became withdrawn. While it contrasted starkly with a behaviorist emphasis that felt like engineering, though, attachment theory still implied that good outcomes could be engineered (Sterns, 2004).

In 1946, in Dr. Spock urged parents to “Trust yourself. You know more than you think you know.” He suggested that parents ignore “expert” advice (and take his). His book, The Commonsense Book of Baby and Child Care, explored specific realms in which this would apply. For example, with respect to toilet training, he suggested that parents “Be friendly and easygoing about the bathroom (Spock, 1946, 193).”

These themes, of taking the wheel or relinquishing the wheel, recurred in the decades going forward. In the 1950s, through B.F. Skinner, behaviorist themes of strict control regained attention. In the mid-1940s, Skinner had offered his own daughter as an extreme example of what effective control might entail, describing in a popular article the first 11 months of her life, which she spent the majority of without clothes in a temperature-controlled box with a spooled sheet that could be changed by turning a crank. According to Skinner, his wife was thrilled to have less of a childcare burden, while the baby was happy, healthy, and essentially thriving (Skinner, 1945).

By the mid-1960s, the opposite trend had been restored. Focused on helping kids reach their fullest potential, and informed by the themes of liberation and humanistic psychology movements, popular books like How to Raise a Brighter Child encouraged parents to maximize their children’s potential by providing rich stimuli, playgroups, and challenging toys (Beck, 1967). At the same time that the authors were interested in empowering children to self-actualize, they were relying on parents to engineer a situation most conducive to the process. The 1970s only further solidified this nurture position.

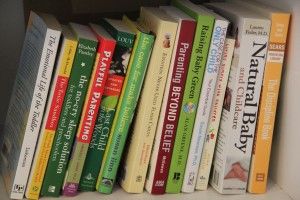

The contemporary state of parenting advice is less bifurcated; it’s more of a choose your own adventure. If what you’re missing is a sense of control, you can find it in books like Parenting with Positive Behavior Support: A Practical Guide to Resolving Your Child’s Difficult Behavior (Hieneman, Childs, & Sergay, 2006) . If what you need is permission to back away from behavioral battles and trust your children and your natural instincts, you can find it in books like Parenting Without Power Struggles: Raising Joyful, Resilient Kids While Staying Calm, Cool, and Collected (Stiffelman, 2012).

The extremes, though, still obscure the challenge. The reality of effective parenting is that it dwells, not in the extremes of control or permissiveness, but precisely in the tense area in between. A good parent will always inhabit this tension. A good parent will ask, “How much am I trying to engineer the outcomes I want? How much am I letting them go? When am I holding the line too tight and when am I being too indulgent?”

You will never definitively know the answers to these questions. The very concept of a solution defies the nature of the problem. Just like effective living, which must by design reside in the tension between birth and death, so must effective parenting exist in the tension between attachment and individuation, connection and separation, control and permission. On some days, that space is a really anxious one to be in. Every move may feel like a misstep. On others, your work may involve vision and revision, and macro and microcorrections just to maintain any sense of balance. But if you’re doing it, really letting the contradictions exist and living in the mess of it all, some days will just be good. The balance will be there, the boundaries clear, the battles (internal and external) will temporarily cease.

References

Beck, J. (1967). How to raise a brighter child: The case for early learning. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hieneman, M., Childs, K, & Sergay, J. (2006). Parenting with positive behavior support: A practical guide to resolving your child’s difficult behavior. Baltimore, MD:Brookes Publishing.

Skinner, B. F. (1945). Baby in a box. Ladies Home Journal, October, http://www.uni.edu/~maclino/cl/skinner_baby_in_a_box.pdf.

Spock, B. (1946). The common sense book of baby and child care. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

Sterns, P. N. (2004). Anxious parents: A history of modern childrearing in America. New York, NYU Press.

Stiffelman, S. (2007). Parenting without power struggles: Raising joyful, resilient kids while staying calm, cool, and collected. New York: Atria Books.

Watson, J. B. (1928). Psychological care of infant and child. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.