Mental Health Stigma

Internalized Weight Stigma and Binge-Eating Disorder

Features, maintaining mechanisms and procedures to address it.

Updated February 28, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Internalized weight stigma is common in people with binge-eating disorder.

- When internalized weight stigma coexists with binge eating, it hinders change and needs to be addressed.

- Internalized weight stigma can be addressed with education and specific cognitive behavioral procedures.

Many patients with binge-eating disorder and higher body weight are self-critical due to their perceived failure to meet their goals of controlling their eating, shape, and weight: a form of negative self-evaluation that may be termed "secondary self-criticism." Secondary self-criticism does not generally need to be addressed in the treatment of the eating disorder because it does not obstruct change. Furthermore, negative self-criticism improves with the successful treatment of the eating disorder, even if it has not been explicitly targeted. However, there is a subgroup of patients with "internalized weight stigma" who have a negative core belief about themselves for their eating, weight, and shape, which maintains the eating disorders and obstructs the change. In this case, the possibilities of treatment success are scarce unless internalized weight stigma is also addressed.

Internalized weight stigma and binge-eating disorder

Internalized weight stigma occurs when a person, applying social negative weight stereotypes to themselves, has negative beliefs about themselves for perceiving having a high weight and other reactions. Patients with internalized weight stigma believe that "they are lazy," "they don't have willpower in controlling eating and weight," "they lack in self-discipline," "they do not have self-control," "they feel like a failure," or "others think they are fat because they lack in self-discipline and willpower."

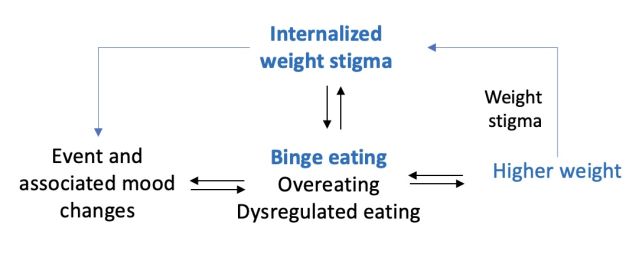

People with internalized weight stigma have frequent negative emotions that are often managed with binge-eating episodes, overeating, and dysregulated eating (Fig .1), common eating patterns in those who suffer from binge-eating disorders. Indeed, high levels of internalized weight stigma seem to influence the variance of eating disorder psychopathology beyond the contributions of fatphobia, depression, and self-esteem in patients with binge-eating disorder. At the same time, the associated low self-efficacy can lead to avoiding the treatment for fear of failing to control eating and weight.

Identifying the presence of internalized weight stigma

Some psychological processes of internalized weight stigma are similar to those operating on low self-esteem. However, they are determined and reinforced by the pervasive weight stigma present in our society that disparages individuals with higher weight.

Internalized weight stigma is characterized by a stable unconditional negative view of self and self-worth for perceiving to have a higher weight and by negative comparisons with others who are without higher weight. Other features are the presence of pronounced cognitive processing biases, extreme rules related to the control of eating and weight goals, and the belief that it is impossible to control eating, which undermines the treatment of binge-eating disorder.

How to address internalized weight stigma

Addressing internalized weight stigma and binge eating is not easy and it is advisable to seek help from a therapist. Below are described some strategies that can be used.

Learning about weight regulation and binge eating

It is fundamental to know that people with higher weight are often the target of denigration and prejudice and have become part of a socially devalued group (weight stigma). This happens because, in our society, individuals with a higher weight tend to be (falsely) considered lazy, unattractive, lacking willpower and self-discipline, and being responsible for their condition. These stereotypes and/or prejudices are based on ignorance, as research has demonstrated that body weight and eating are regulated by a complex combination of genetic and environmental factors and that weight is only in part under the control of the individual.

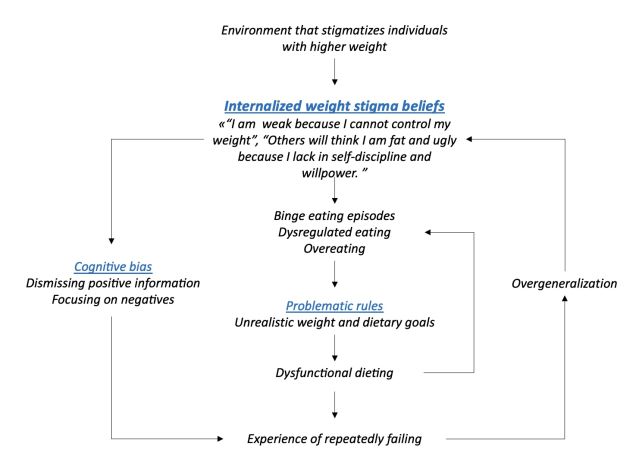

Creating the personal formulation

The personal formulation is a visual representation (a diagram) of the processes that maintain the internalized stigma and its relationship to binge eating episodes (see an example in Figure 2). It should be done collaboratively with a therapist and include the factors that need to be addressed during the treatment (it is considered the road map of the treatment).

Addressing cognitive processes

1. Negative beliefs about themselves and other reactions. People with internalized weight stigma have negative beliefs about themselves and how others evaluate them. For example, the belief “I am lazy and weak because I cannot control my eating and weight” is often associated with the belief “Others will think I am fat and ugly because I lack self-discipline and willpower.” They think they are responsible for causing and resolving their binge eating and higher weight. The belief of not having enough willpower to control eating hurts the control of eating, maintaining binge-eating episodes, and is often implicated in the interruption of the treatment. At the same time, the negative beliefs regarding the reactions of others, more common in those who had experienced weight stigma experiences, may lead the individuals to avoid certain things (e.g., traveling or eating at restaurants) or places because they are frightened. In doing so, they lose the opportunity to obtain evidence that challenges or disconfirms their beliefs about others’ reactions.

2. Cognitive biases. The most common cognitive biases to address are:

- Noticing negative qualities related to the control of eating while overlooking positive ones.

- Selective attention to information is consistent with negative self-views related to weight control, eating, and other reactions.

- Over-generalization from any instance of not succeeding to control eating to be a failure.

- All-or-nothing thinking (e.g., “If I am not normal weight, I must be weak”).

3. Problematic rules or expectations. People with internalized weight stigma often have problematic rules about the control of eating and weight. These rules are intermittently applied to cope with the negative beliefs that one is unable to control their eating and weight. They are expressed by the intermittent attempts to follow extreme and rigid diets and by having unrealistic weight loss expectations. These rules or expectations place heavy demands on the person, and they must live up to them. Typical examples are the following: “I have no willpower; I have to follow an extreme and rigid diet perfectly”; “The others think I have no eating control”; “I always have to eat less than the others on social occasions.”

4. Experiences of repeated failure and generalization. Problematic rules regarding eating control and weight goals are inevitably broken, as they are extreme and rigid, combined with cognitive bias. Therefore, the individuals, having repeated experiences of failure in controlling eating and being unable to reach the unrealistic weight goals, generalize from these perceived failures and see themselves as a ‘failure,’ confirming their negative belief about themselves.

Exploring the origins of the internalized weight stigma

It is also helpful to conduct a thorough "historical review" with the therapist to reflect on what may have contributed to the development of internalized weight stigma. This analysis can help understand how the negative beliefs about themselves and other reactions have been developed and maintained, question the old appraisals of past experiences, and develop new ones.

Arriving at a Balanced View of Self-Worth

The final step in addressing internalized weight stigma is to accept a more balanced (i.e., less negative) view of themselves. The goal is to arrive at a more realistic appraisal of one's qualities. For example, the judgment "I am weak because I don't lose weight" may be questioned by reviewing times when one has been strong, especially when it would be acceptable or understandable not to be strong (e.g., in following a strict diet). While such a re-appraisal might lead to identifying areas where one would still like to make changes, this does not warrant the conclusion that one is "weak."

This type of re-appraisal should include the notion of "acceptance" and the idea that a balance needs to be struck between "acceptance" and "change." One can change aspects of life (e.g., how one eats within certain limits) However, there are other aspects of life that one cannot change (e.g., one's shape and height; one's early experiences) or that can only change to a limited extent or with great difficulty (e.g., one's weight in the long-term; one's family; other people).

The goal is to behave consistently with this new balanced appraisal of themselves and observe the results. Examples might include asking for help when previously this was viewed as a sign of weakness; challenging criticism on weight and eating as ignoring them and responding to criticism assertively, or being more active, for example, joining a group that fights prejudice against people with higher weight; experimenting with making new friends who don't have biases about weight.

References

Calugi, S.; Segattini, B.; Cattaneo, G.; Chimini, M.; Dalle Grave, A.; Dametti, L.; Molgora, M.; Dalle Grave, R. Weight Bias Internalization and Eating Disorder Psychopathology in Treatment-Seeking Patients with Obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15 (13), 2932.

Cooper, Z.; Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R. Controlling binge eating and weight: a treatment for binge eating disorder worth researching? Eat. Weight. Disord. 2019, 25 (4), 1105-1109. DOI: 10.1007/s40519-019-00734-4.

Durso, L. E.; Latner, J. D.; White, M. A.; Masheb, R. M.; Blomquist, K. K.; Morgan, P. T.; Grilo, C. M. Internalized weight bias in obese patients with binge eating disorder: associations with eating disturbances and psychological functioning. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45 (3), 423-427. DOI: 10.1002/eat.20933 From NLM.

Pearl, R. L.; Bach, C.; Wadden, T. A. Development of a Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Internalized Weight Stigma. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 2022. DOI: 10.1007/s10879-022-09543-w.