Eating Disorders

Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Elimination Diets

Why they can trigger or aggravate feeding and eating disorders.

Posted September 3, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Treating functional gastrointestinal symptoms often involves diets that involve eliminating specific foods.

- Elimination diets, when used appropriately, can relieve the physical symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in some people.

- Elimination diets may trigger or aggravate feeding and eating disorders.

Abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, constipation, and diarrhea are common gastrointestinal symptoms reported by people, but often they do not have an organic explanation. In these cases, the doctors attribute the symptoms to the "disorders of gut-brain interaction," formerly known as functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Disorders of gut-brain interaction, such as irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and functional constipation, account for at least one-third of specialist visits to gastroenterology clinics and affect up to 40 percent of people in their lifetime. They are more prevalent in women (49 percent) than in men (37 percent), and in two third of cases, the people suffer from chronic and fluctuating symptoms.

The causes of gut-brain interaction disorders are not known. However, according to the most recent biopsychosocial theory, they are characterized by a bidirectional dysregulation of gut-brain interaction across the gut-brain axis.

In recent years, treating disorders of gut-brain interaction has often proposed diets that involve eliminating specific foods. This approach derives from the observation that about two-thirds of patients with irritable bowel syndrome report that their symptoms are associated with the intake of some specific foods.

Studies on the effectiveness of elimination diets, such as the FODMAP (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols) elimination diet, which reduces the intake of certain foods that tend to ferment in the intestine and retain water from the mucous membrane, have shown that, when used appropriately, they can relieve the physical symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in two third of patients.

Unfortunately, the effects of the FODMAP diet have not been studied for more than six weeks. Furthermore, no studies examined the effect of the food reintroduction period, which should occur after two to six weeks of the elimination phase and the gastrointestinal symptoms under control. Therefore, it is not excluded that improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms attributed to dietary modifications are merely the consequence of a placebo or nocebo effect.

Recent studies have also reported that elimination diets may trigger or aggravate feeding and eating disorders in some people.

Elimination Diets and Eating Disorders

Chronic illnesses, such as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, are often associated with a feeling of loss of control. In these cases, adhering to specific and rigid diets may become attractive because it can offer some control over an unpredictable illness with embarrassing and stigmatized symptoms. In some people, the false sense of control achieved with dieting may trigger the onset of eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, which has a central role in their maintenance.

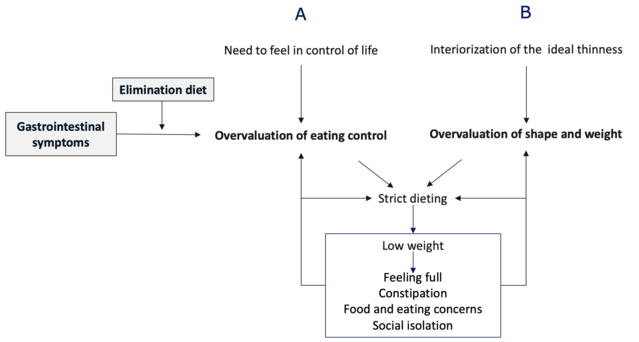

According to the cognitive behavioral theory, gastrointestinal symptoms and elimination diets precipitate and maintain eating disorders as they trigger the development of the “overvaluation of eating control” (i.e., evaluating themselves predominantly or even exclusively in terms of the ability to control eating) and the consequent adoption of a strict diet by shifting the need for control in general on the control of eating.

Dietary restriction and low weight are associated with several starvation symptoms, such as concerns about food and eating, feeling of early fullness from slowed gastric emptying, constipation, and social isolation, which intensify the need for eating control and the adoption of strict and extreme dietary rules. This mechanism is also present in people with an overvaluation of shape and weight who adopt a strict diet to lose weight and change their body shape (Figure 1).

The prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms has been found in about 86 percent of patients with anorexia nervosa, and about 30 percent of people with functional gastrointestinal disorders evaluated through an online survey met the criteria for an eating disorder. In addition, greater adherence to the FODMAP diet is associated with a higher probability of having an eating disorder in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

N.B. The overvaluation of eating control often coexists with the overvaluation of shape and weight, but not always. When it is in isolation, people are not concerned about their shape and weight and tend to base their self-evaluation mainly on how, when, where, and what they eat. These cases have been sometimes termed “non-fat phobic anorexia nervosa.”

Elimination Diets and Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

The main feature of ARFID is avoidance or restriction of food intake associated with failure to meet requirements for nutrition or insufficient energy intake through oral intake of food with significant clinical consequences, such as weight loss, nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, or marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake is not related to the concerns about shape and weight but to one or more of the following characteristics: (i) apparent lack of interest in eating or food; (ii) avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food; (iii) concern about aversive consequences of eating.

When associated with concerns that certain foods may trigger or accentuate gastrointestinal symptoms, the third characteristic explains why clinicians often inappropriately prescribe elimination diets to people with ARFID. Indeed, one study found almost 90 percent of patients with ARFID referred to a single center of Behavioral Medicine services had been prescribed a low FODMAP diet.

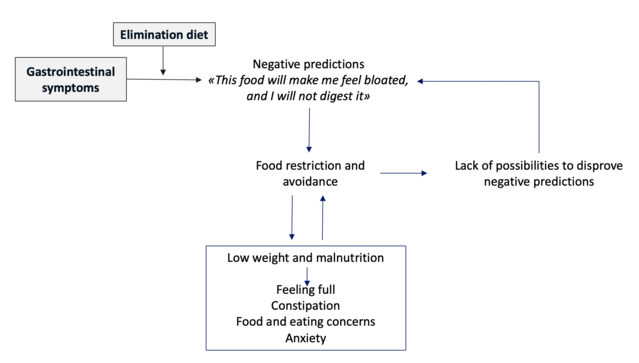

The elimination diets can trigger and maintain ARFID with the mechanisms shown in Figure 2. According to cognitive behavioral theory, some people, when they have gastrointestinal symptoms associated with the intake of certain foods, develop negative predictions (e.g., “This food will make me feel bloated”), which they manage with the avoidance/restriction of food.

This behavior produces an impairment of the nutritional status and sometimes low weight and the development of starvation symptoms (e.g., feeling of fullness from reduced gastric emptying, constipation, concerns about food and eating, increased anxiety), which maintain and accentuate avoidance/restriction of food. Furthermore, the avoidance/restriction of food makes people miss the opportunity to disprove their negative predictions.

The prevalence of ARFID symptoms in the adult gastroenterological population is about 10-20 percent, while in the pediatric population, it varies between 1.5 percent and 3.9 percent. Interestingly, gastroenterologists rarely make the diagnosis of ARFID.

References

Black, C. J., Drossman, D. A., Talley, N. J., Ruddy, J., & Ford, A. C. (2020). Functional gastrointestinal disorders: advances in understanding and management. Lancet, 396(10263), 1664-1674. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32115-2

Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2021). Complex cases and comorbidity in eating disorders. Assessment and management. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Simons, M., Taft, T. H., Doerfler, B., Ruddy, J. S., Bollipo, S., Nightingale, S., . . . van Tilburg, M. A. L. (2022). Narrative review: Risk of eating disorders and nutritional deficiencies with dietary therapies for irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 34(1), e14188. doi:10.1111/nmo.14188

Thomas, J. J., & Eddy, K. T. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Children, adolescents, and adults: Cambridge University Press.