Eating Disorders

The Link Between Excessive Exercising and Eating Disorders

Features and management.

Posted February 1, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Excessive exercising is a common feature in adolescents with eating disorders.

- Excessive exercising increases the risk of overuse injuries, bone fractures, cardiac complications, and psychosocial impairment.

- Excessive exercising maintains a person's eating disorder through several mechanisms and is a predictor of poor outcome.

- Cognitive behavior therapy actively involves the patients in addressing excessive exercising with specific strategies and procedures.

Exercising is defined as excessive when its duration, frequency, or intensity exceeds what is required for physical health and increases the risk of physical injury. It is a form of exercise associated with a subjective sense of being driven or compelled to exercise. It has priority over other activities (e.g., school) and is associated with feelings of guilt and anxiety when postponed.

Excessive exercising precedes dieting in a subgroup of people with an eating disorder and is a common feature in adolescent patients with eating disorders, particularly those underweight.

Forms and functions of excessive exercising

Excessive exercising takes three major forms, including:

- Excessive daily activity (e.g., standing rather than sitting and walking excessive amounts).

- Exercising in a normal manner but to an extreme extent (e.g., going to the gym three times every day).

- Exercising in an abnormal manner (e.g., doing excessive numbers of push-ups or sit-ups).

Excessive exercising may also be classified according to its functions:

- To control shape and weight. This is the most common function of exercise adopted by people with eating disorders, and may be compensatory or non-compensatory. Compensatory exercising may also be pre-emptive, with patients seeking to "burn off" calories before ingested (so-called "debting"). Some feel that they can only eat if they have exercised beforehand. Other compensatory exercisers may adjust their physical activity levels in line with what they have already eaten.

- To modulate mood. Excessive exercising may also be used to neutralize or reduce awareness of adverse emotional states.

Associated features

Excessive exercising in people with eating disorder patients is associated with several distinct features, including higher eating disorder psychopathology and dietary restraint, higher general psychopathology (particularly anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms), specific personality features (i.e., higher levels of perfectionism persistence and tolerance of frustration), low body mass index (BMI), and younger age.

Negative consequences

Excessive exercising has several negative consequences. It increases the risk of overuse injuries, bone fractures, and cardiac complications. It requires secrecy and subterfuge and produces feelings of guilt. It takes up a lot of time and is mainly practiced alone; it impairs interpersonal relationships and school/work performance.

Maintenance of eating disorders

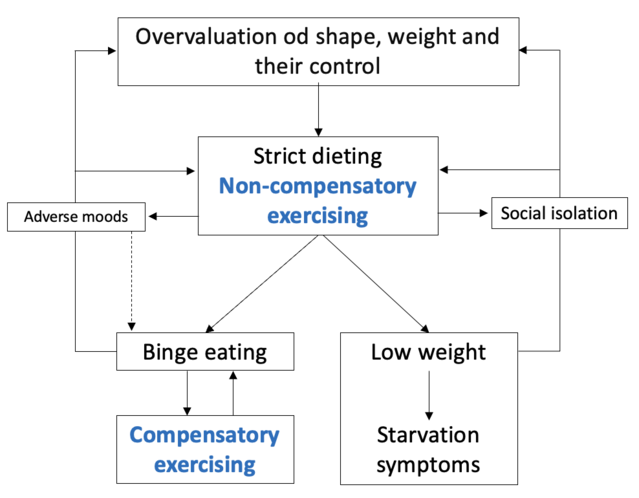

Excessive exercising maintains eating disorder psychopathology through several possible mechanisms (Figure 1):

- By contributing (in association with dietary restriction) to weight loss and serving to maintain low body weight.

- By increasing the risk of binge-eating episodes. This mechanism may be established in both compensatory and non-compensatory exercising.

- By intensifying the overvaluation of shape, weight, and their control. The more intensive and frequent the exercise to control shape and weight, the more the individual is locked into their concerns about shape and weight.

- By promoting social isolation. Individuals with eating disorders typically exercise alone, and inevitably reduce the time spent with others. In turn, the resulting marginalization of social life increases their overvaluation of shape, weight, and their control.

- By modulating mood in a dysfunctional way. Exercising that has the role of modulating adverse mood states may seem beneficial in the short term. However, it will become dysfunctional in the long term because it obstructs more functional ways of addressing day-to-day difficulties associated with negative emotions.

Management of excessive exercising

The enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) of eating disorders, a psychological treatment endorsed by the UK’s independent and highly regarded National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), addresses excessive exercising with the following main strategies and procedures.

The first step is to assess whether or not the exercise that the patient is engaging in is, in fact, excessive. For some patients, it is difficult to admit that they have a problem in this regard, as excessive exercising is a habit, and, in any case, they may feel that their exercise is healthy.

To overcome this obstacle to change, the therapist should ask the patients to monitor their exercising habits, record all episodes on their monitoring record, and then report the type of exercise, its duration, and its reasons. The clues indicating the presence of excessive exercising, to be shared with patients, are the following:

- Doing exercise that interferes with important activities (e.g., school)

- Exercising in inappropriate moments or environments

- Feeling obliged to exercise, even if this may hurt

- Feeling guilty if exercise is not done for any reason

The second step in the procedure is to educate them about the negative aspects of excessive exercising (see above), and the benefits of adopting a healthy exercise.

The third step actively involves the patients in deciding to interrupt their excessive exercising. The goal is that patients choose to do this rather than having the decision imposed upon them. As patients usually tend not to see their exercising as a problem, but rather as a positive way of controlling shape and weight or modulating mood, this is often a difficult task. Furthermore, most patients are highly concerned about the perceived negative consequences of stopping or reducing exercise on body weight and shape.

The therapist must point out (using the patient’s personal formulation) that excessive exercising plays a central role in maintaining their eating disorder (see above). The therapist should also validate patients’ experience by acknowledging the perceived positive effects of exercising and (if present) their ambivalence and the fear to change.

To help them make this decision, patients should be helped to create the pros and cons of the changing table. The therapist should also emphasize that change is necessary to liberate themselves from the adverse effects of this type of exercise and overcome the eating disorder. With patients who report the fear of losing control over weight if they interrupt their exercising, the therapist should reassure them that adopting a healthy lifestyle is the best way to maintain long-term weight control. Finally, the patients should be helped to conclude that they want to attempt to change.

If the patient has decided to address their excessive exercising, the fourth step is to agree with them which procedure to use. At this stage, patients should always be informed that in the first few days of tackling their behavior, their levels of anxiety and concern about shape and weight might increase, but will gradually decrease, and this will be associated with gaining the benefits of leading a healthy lifestyle. The main procedures to suggest to such patients are the following:

- Monitoring exercise in real-time. Patients are instructed to record the events, thoughts, and emotions that precede exercising in real-time in the Comments column of their monitoring record. If they do this before they start exercising, they will become aware of what they are doing, thinking, and feeling at the precise time that the urge to exercise is upon them, which will make it easier for them to resist doing it.

- Encouraging healthy exercising. When they are in a stable medical condition, patients should be encouraged to substitute excessive exercising with healthy exercising. Social exercising, in particular, is a valuable means of escaping from isolation (a factor implicated in the maintenance of eating-disorder psychopathology), it can be used to practice body exposure, and it may help to dispel the urge to exercise to accept weight gain and changes in shape. It is also essential that patients break any link between eating and exercising, and interrupt any form of compensatory exercising (e.g., to compensate for excessive calorie intake or burn calories in advance of eating).

- Addressing the urge to exercise. This will involve the patients engaging in activities that make the exercising less likely or riding out the urge (urge surfing).

- Addressing events and associated mood changes that trigger exercising. Patients are helped to practice proactive problem solving to find alternative solutions to cope with events and associated negative emotions.

- Limiting exercising. If the procedures in the previous point are not successful in helping a patient deal with the urge to exercise, the therapist may consider, with the patient’s consent, involving parents or a trusted person to help the patient to at least limit their exercising using the same procedures described. However, if this fails, the therapist should consider whether it would be wise to intensify the treatment (e.g., by switching to intensive outpatient or residential treatment).

- Discontinuing competitive sports. The intense exercise regime practiced by individuals in high-level competitive sports may be a potent maintenance mechanism for eating-disorder psychopathology and can be dangerous for health. The therapist should encourage these people, potentially with input from their coach, to ‘temporarily’ suspend both practice and competitions. Patients who practice competitive sports can be helped to accept this recommendation by emphasizing that rest, and achieving a healthy weight, will be necessary to improve sports performance.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Dalle Grave, R. (2009). Features and management of compulsive exercising in eating disorders. Physician and Sportsmedicine, 37(3), 20-28. doi:10.3810/psm.2009.10.1725

Dalle Grave, R., & Calugi, S. (2020). Cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., & Marchesini, G. (2008). Compulsive exercise to control shape or weight in eating disorders: prevalence, associated features, and treatment outcome. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(4), 346-352. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.12.007